The Cambodian government’s suppression of Radio Free Asia and Voice of America broadcasts was front page news in The Cambodia Daily on August 29, 2017. (Hean Socheata | VOA Khmer)

Community Stories

Journalists Feel Like ‘Tall Trees’ Buffeted by Wind

A crackdown on free expression has seen media outlets shuttered, journalists jailed or exiled, and Cambodians wary of speaking their minds in public before the July 29 election.

A year ago, Morm Moniroth was one of the best-known voices in Cambodia, his trademark tenor booming out from Radio Free Asia’s nightly news broadcast as he reported on hot-button issues like border disputes, politics and court cases.

Today, he is a farmer, eking out a living on a small plot of land where he grows mangoes and lemons. He asked VOA Khmer not to reveal the location of his farm, for fear of being targeted by local authorities.

Moniroth’s decision to leave journalism for agriculture wasn’t a choice, but a necessity, he says. Amid an ongoing crackdown on freedom of expression and the media in Cambodia, Radio Free Asia (RFA) was hit by the Cambodian government with an enormous tax bill.

The radio station shut down its operations in the country, citing mounting intimidation against its reporters, but that did not satisfy the government, which declared it would be considered illegal for anyone to maintain any association with the organization.

Now, RFA’s former reporters and radio technicians – roughly 50 employees – are living in fear. Some are in hiding. Others have quit journalism and do not foresee a future in which they can return to their careers. Two of them are living out their colleagues’ worst nightmares: they were arrested in November and thrown into prison, accused of espionage for reasons the government has declined to explain.

“I devoted my life to my work,” Moniroth said. “Now I want to remain silent and live my life as an ordinary person. Being too well-known is like being a tall tree, first to be affected by the wind.”

Trees in the Wind

It is not just RFA that has felt the heat. In the months leading up to the country’s sixth general election, scheduled for July 29, press freedom has taken a severe hit. Journalists and media advocates say the current situation is the worst in memory, with many reporters self-censoring, leaving journalism for less contentious careers and in a few cases even fleeing the country.

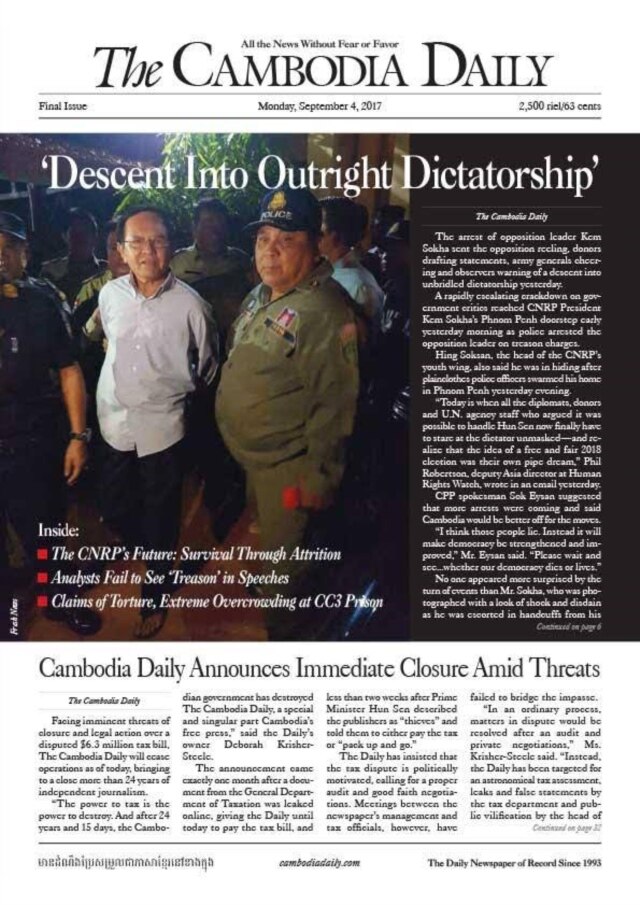

The Cambodia Daily bannered a pull-no-punches headline in its last edition. (Cambodia Daily)

One of the country’s leading English-language newspapers, The Cambodia Daily, was forced to shut down in September after being hit with a $6.3 million tax bill from the government. Its crosstown rival, the Phnom Penh Post, was taxed so heavily that its Australian owner sold it in May to the owner of a public relations firm that has done work for Prime Minister Hun Sen.

In the most recent World Press Freedom Index, released in May, Reporters Without Borders dropped Cambodia 10 places in its rankings, to 142nd out of 180 countries. The group said the decline was one of the steepest in the region, adding, “Cambodia seems dangerously inclined to take the same path as China after closing dozens of independent media outlets.”

“Political issues are like heat and the media is like ice,” said Phak Seangly, a reporter at the English-language Phnom Penh Post. Seangly has been with the Post for eight years, and says that the current political climate is the most difficult of his career.

His wife, Chhiev Hong, has begged him to stop doing journalism for the sake of their 9-year-old son and 6-year-old daughter. Although Seangly wants to continue, he has become more tentative about publishing hard-hitting stories.

“I have many stories in hand, but the election is approaching, so we have to be careful and think of our safety,” he said. “No one prohibits us from reporting, but due to the situation, I feel that I need to step back from reporting critical issues.”

Pov Meta, the news editor for independent radio station Voice of Democracy (VOD), said his reporters have also become more cautious due to fear that they would get into trouble.

VOD has already faced pressure, with many of its stations abruptly taken off the air by the government in August last year, along with stations broadcasting VOA and RFA.

Just as troubling to Pov Meta is the fact that many sources who used to be unafraid to speak freely are now clamming up. He said this has been the first time in his career that he has faced so much fear among Cambodians about speaking out.

“They don’t dare to comment like before,” he said. “They just speak off the record, not on the record.”

In a statement issued in June, U.N. human rights experts said they were also seriously concerned about the media environment ahead of the July 29 national elections, citing a highly restrictive new code of conduct for journalists issued by the National Election Committee as well as various statements made by the government.

Among other restrictions, the code says that journalists cannot create “confusion and loss of confidence,” and are forbidden from expressing “personal opinion or prejudice,” provisions that press freedom groups said were worryingly vague.

“The prohibitions on the media in the code raise serious concerns relating to media freedoms,” the U.N. said. “These prohibitions use broad and imprecise terminology that could lead to sweeping restrictions on the media that would be incompatible with international standards.” (In defense of the code, the government said it was important to ensure “transparency and responsibility” in the news media.)

Similar rules were applied to journalists in advance of last year’s commune elections, with chilling consequences in at least one case.

Aun Pheap, a reporter who worked at The Cambodia Daily before it closed, is seeking political asylum in the United States. (Cambodia Daily)

Jail and Exile

Like his counterparts at RFA, Aun Pheap was riding high a year ago. The 54-year-old was a senior reporter at The Cambodia Daily, widely respected for his reporting on illegal logging, land grabs and issues facing ethnic minorities.

Then, on a trip to Ratanakiri province to report on the June 2017 commune elections, he and his reporting partner, Canadian journalist Zsombor Peter, were detained by police for asking villagers simple questions about their political preferences.

Although this is not against the law, local officials claimed that they were guilty of violating the National Election Committee’s pre-election rules. The two were ultimately charged with “incitement to a felony,” which can carry prison time of up to two years.

Peter left the country permanently, while Pheap fled to Bangkok in October and was granted U.N. refugee status in January. He has resettled in the U.S., but is still waiting for his wife and children to receive permission to join him. Until then, they are living a bare-bones existence in Thailand.

Uon Chhin and Yeang Sothearin, journalists formerly with Radio Free Asia (RFA), arrive in a police vehicle for a bail hearing at the Appeal Court in Phnom Penh on April 19, 2018. (Samrang Pring | Reuters)

Even more disturbing is the plight of Yeang Sothearin and Uon Chhin, the ex-RFA reporters jailed in November last year for reasons that remain unclear.

The government has accused them of “espionage,” but has provided no evidence for the claim. It has also claimed that they had continued to work covertly for the radio station, but has not explained whether or how that constitutes espionage. Amnesty International has called the charges “trumped up.”

Sothearin’s wife, Lam Chantha, said her husband stopped working for RFA as soon as its Cambodian bureau closed and that she could not imagine why he was jailed, other than in retaliation for his previous journalistic work.

“I think he reported the truth and it affected someone,” she said.

“Since my husband has been in trouble, I can’t even sleep,” she said. “I am concerned about him and don’t know who can help him. I am not educated and he’s been accused and I don’t know when he will be released.”

Local journalists have been especially shaken by the plight of Sothearin and Chhin and the suffering their imprisonment has caused their families.

Chhiev Hong, the wife of Post reporter Seangly, said the situation made her frightened for her husband’s safety.

“I am terribly worried about him. We are worried about his safety when he comes home late at night. And if he goes to a provincial area, I can’t even sleep, waiting up for him, whatever time he comes back,” she said.

Pov Meta, of Voice of Democracy, said the fear of going to jail like Yeang Sothearin and Uon Chhin was affecting his team’s work.

“Journalists are scared of reporting sensitive stories,” he said.

Yeang Sothearin (Left) and Uon Chhin (Right). (Radio Free Asia)

A Push to be ‘King of Facebook’

In May 2017, when Southeast Asian leaders gathered with foreign investors, bankers and financial experts for the World Economic Forum in Phnom Penh, Prime Minister Hun Sen publicly dressed down reporters from The Cambodia Daily and Radio Free Asia for being too critical of him and his government.

The Cambodia Daily was “opposing me all the time,” he said, while Radio Free Asia was “radio against the government.”

Now, just over a year later, and shortly before the critical July 29 election, both outlets have been forced to shut down in Cambodia. Media experts say this is not a coincidence.

The prime minister and his government have long had a tendency to see independent media “as an arm of the opposition,” said Sebastian Strangio, author of “Hun Sen’s Cambodia,” who spent years as a journalist based in Phnom Penh.

Strangio said the recent increase in pressure on independent media appeared orchestrated to eliminate sources of information ahead of the July 29 elections, which the Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) has virtually guaranteed it will win by dissolving its closest competitor, the Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP).

The media crackdown kicked into gear shortly after the 2017 commune elections, in which the CNRP posted a strong showing, garnering 46 percent of the popular vote. The CPP still won the majority of commune council seats, but the results indicated that the opposition party would be a strong challenger to the CPP in the national elections.

“I think it speaks to the government’s paranoia as to how the July 29 election will play out – even absent the CNRP – as well as representing its final reckoning with the independent forces unleashed by the Paris peace settlement in the 1990s,” Strangio said of the media crackdown.

In addition to suppressing traditional media that is not pro-government, the CPP has made a push to dominate the internet, which the CNRP used to its advantage during the 2013 elections, attracting many young people through its mastery of platforms like Facebook.

The government has ordered internet service providers to block The Cambodia Daily’s website, and in May announced the formation of an inter-ministerial task force “to prevent the spread of information that can cause social chaos and threaten national security.”

A number of Cambodian citizens have been arrested or detained for making political statements on Facebook, including several people who fell prey to a new lese-majeste law that criminalizes criticism of the king. Sharing information about a CNRP-spearheaded initiative to boycott the election has also been declared illegal.

Hun Sen, on the other hand, has enjoyed undiminished free speech, including hours of political orations that he regularly broadcasts via his Facebook page, Samdech Hun Sen, Cambodian Prime Minister, during which he makes promises and blasts his opponents. These opinions are then duly shared by pro-government news sites and ruling party officials.

Instead of using independent media to find out what is happening in Cambodia, the premier now turns to Facebook to communicate with both his subordinates and members of the public, whom he has encouraged to file complaints to him using the social media site.

The premier’s Facebook page also brims with photographs of him posing with garment workers and students, or relaxing at home with his growing brood of grandchildren, in a seeming effort to make him seem more approachable to Cambodia’s young and increasingly tech-savvy population, 40 percent of whom are avid Facebook users.

“Paralleling his offline consolidation of power, Hun Sen also reinforced his position as Cambodia’s king of Facebook during the last eight months,” said Astrid Noren-Nilsson, a lecturer at Lund University in Sweden who specializes in Cambodian politics.

But it is unclear whether these Facebook activities are doing much to improve Hun Sen’s public image. Judging from the results of the June elections, “the benefit has been minimal,” Strangio said.

“No amount of Facebook spin can replace economic and politics reforms designed to improve the livelihoods of ordinary Cambodian people.”

Khem Sreymom, a 38-year-old former garment worker in Phnom Penh, said she was not interested in following news via the prime minister’s Facebook page and missed broadcasts from RFA and other shuttered media outlets.

“When they had the radio, I could listen,” she said. “It was easy to turn on. I don’t follow news like before, now that it is on Facebook. Sometimes, I miss the programs. When I listened to RFA news, I knew about social issues, injustices, violations and abuses of the law. News that the government-affiliated media doesn’t report, RFA reported.”

San Sel is a onetime RFA reporter based in Phnom Penh. Now working in marketing, he worries about what limited media options will mean to Cambodians. (Khan Sokummono | VOA Khmer)

San Sel, another former RFA reporter, took a job in marketing after the crackdown, and is not sure he will ever be able to return to journalism. His career may have taken a hit, but his biggest fear is that the clampdown on media will cause fewer new ideas to be shared and constrict social development in Cambodia.

When press freedom is dead, “freedom of speech of the people is also affected,” he said.

“When there is little independent news, few new ideas are formed. Ideas are small,” he said, adding, “Is this a good or a bad idea for our society?”