A solider rests in a hammock nearby a newly established base camp in Smarch village of Siem Reap province’s Tram Sasar commune, on Dec. 21, 2017. Although hundreds of soldiers registered to vote there in September, only a few were present at the camp in December. (Sun Narin/VOA Khmer)

Community Stories

Ready, Aim, Vote

Cambodia’s Military Prepares to Battle an Uncontested Election

Tram Sasar Commune, Siem Reap Province, Cambodia This tiny, dust-swept hamlet in the middle of nowhere would seem to have very little military strategic value. But for several days in September, hundreds of Cambodian soldiers streamed in.

The soldiers told locals they had been sent from neighboring Oddar Meanchey province to set up a new military base. But most of them left shortly after they arrived. Only around a dozen men remained to staff the brand-new base, which is little more than a corrugated-metal shack erected behind a dried-up rice field.

This is because their purpose was not to defend the nation or its borders. Instead, the soldiers came to register to vote and “defend the election,” according to Tram Sasar’s chief of police, Eum Yun.

Camouflage uniforms and accessories hang inside the makeshift base camp in Tram Sasar commune of Srey Snam district on Dec. 21, 2017 Narin/VOA Khmer

“They are stationed here to prepare to defend the next election in 2018.”

A rice field near a new military camp in rural Tram Sasar commune, Siem Reap province, where 1,430 new voters registered in September, many of them soldiers who later returned to their home bases in neighboring Oddar Meanchey province. (Julia Wallace/VOA Khmer)

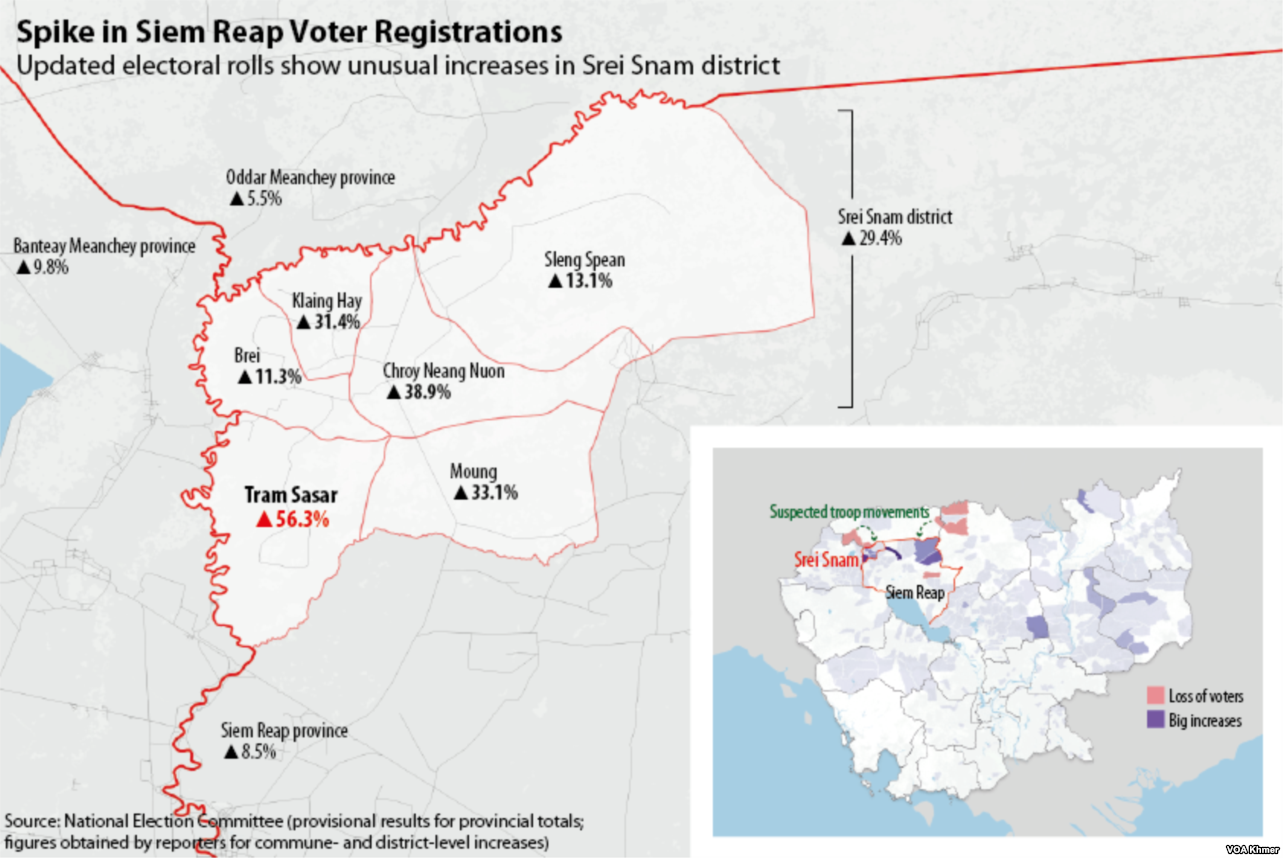

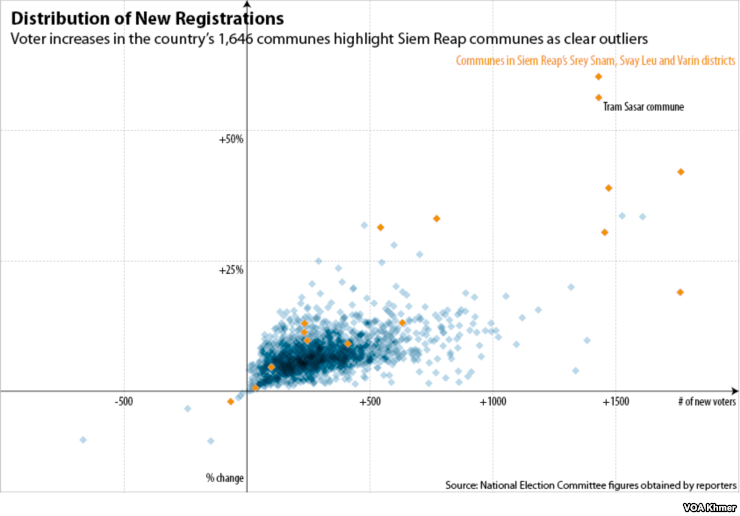

The soldiers arrived just in time to establish their residence for the upcoming national election, scheduled for July 2018. Voter rolls were open between September 1 and November 9 last year. During that period, 1,430 new arrivals registered to vote in Tram Sasar, swelling the remote rural commune’s voting population by 56.3%. (The average increase nationwide over the same period was just 6.4%.)

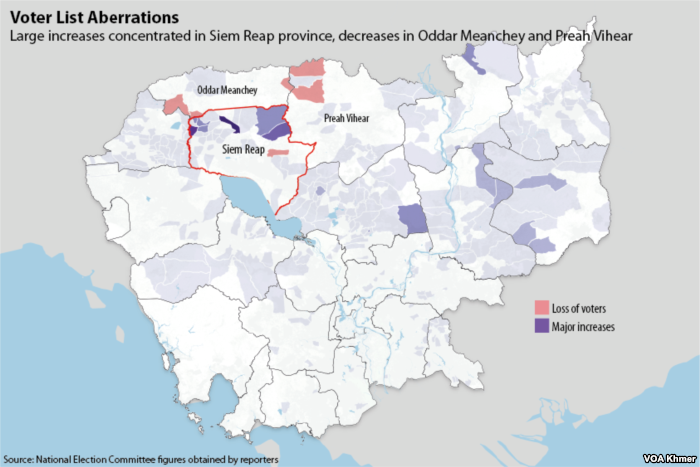

This map shows communes in Cambodia with noticeable changes in voter registration. The most dramatic changes of losses and increases in voter registration occurred in Siem Reap, Oddar Meanchey, and Preah Vihear provinces. Less noticeable changes in other parts of the country can be explained by recent demographic patterns. Data source: Cambodia's National Election Committee. (Michael Dickison/Julia Wallace for VOA Khmer)

(Michael Dickison/Julia Wallace for VOA Khmer)

“Yes, there is registration from the soldiers,” Eum Yun said. “They came to protect here, so they have to register here.”

He confirmed that he had personally approved the registration of the hundreds of military personnel who arrived in Tram Sasar in September as new voters, along with many of their family members. He said there were no soldiers living in the area before.

“They are stationed here to prepare to defend the next election in 2018,” he said.

(Michael Dickison/Julia Wallace for VOA Khmer)

Marching Ahead

In a country whose ruling party has dissolved its primary opposition, the Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP), “election defense” may seem like overkill. But the CNRP almost won the last national election in 2013, when, days before the vote, Cambodia yielded to international pressure and allowed opposition leader Sam Rainsy to return from exile to campaign. Five years later, registering soldiers looks a lot like a defensive move made by a government determined to retain the veneer of electoral legitimacy, even as it has overseen a large-scale crackdown on dissent over the past six months that has drawn international condemnation and cuts in aid from the United States and the European Union.

Although Cambodia is nominally a democracy, the ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) has held power in some form since 1979 and has near-total control over the country’s military, as well as the police force, court system and most other state institutions. A VOA investigation has revealed that the influx of soldiers into Tram Sasar commune was part of a much larger movement of voters into northern Siem Reap province during the 70-day registration period in 2017, many of whom appear to be military personnel and their families. Nearly 6,000 people arrived from the highly militarized northern provinces of Oddar Meanchey and Preah Vihear, of whom almost 90% were men.

Multiple communes in northern Siem Reap saw large spikes in voter registration, far exceeding the national average, that cannot be explained by any known settlement patterns.

In Srei Snam district, where Tram Sasar is located, two other military bases were also established during the election registration period, according to Ho Chhin, who served as a district official until November, when the opposition party was dissolved and he lost his job.

Those bases were located in Klaing Hay and Chroy Neang Nguon communes, which also saw large spikes in voter registration last year: 31.4% and 38.9%, respectively. Another commune, Moung, had a pre-existing military base known as Base Station 41, and had a 33.1% increase in registered voters. The district’s two remaining communes, Sleng Spean and Brei, both registered new voters at approximately double the national average.

This is not the first evidence of politically motivated troop movements in the area. During the June 2017 local elections, the Phnom Penh Post reported that around 800 soldiers from Preah Vihear province were trucked into Ta Siem district in northern Siem Reap to vote there. Multiple former opposition officials from Siem Reap who spoke to VOA said that they had received sporadic reports of soldiers voting in the June commune elections, but that many more soldiers had arrived during the September registration period.

“If they came here for election defense, why not on Election Day? And there are police, military police. Why soldiers?”

A provision in Cambodia’s election law allows soldiers to register in areas they are assigned to guard on Election Day, but under no circumstances should hundreds or thousands of soldiers be needed to protect rural polling stations, Ho Chhin said.

“They came here for registration,” he said. “If they came here for election defense, why not on Election Day? And there are police, military police. Why soldiers?”

A soldier rests in a hammock at the newly established military camp in Smarch village of Siem Reap province’s Tram Sasar commune on Dec. 21, 2017. Although hundreds of soldiers registered to vote there in September, only a few were present at the camp in December. (Julia Wallace/VOA Khmer)

Srei Snam’s governor, Neak Nerun, grew angry when asked by a VOA journalist about the appearance of multiple new military camps in his district.

“I am wondering why you, VOA, are curious about the camps in the communes. Are you the enemy of the soldiers? Camps can be anywhere. It is under the Ministry of National Defense. Is it wrong to have the soldier camps in the communes?”

Defending the Election

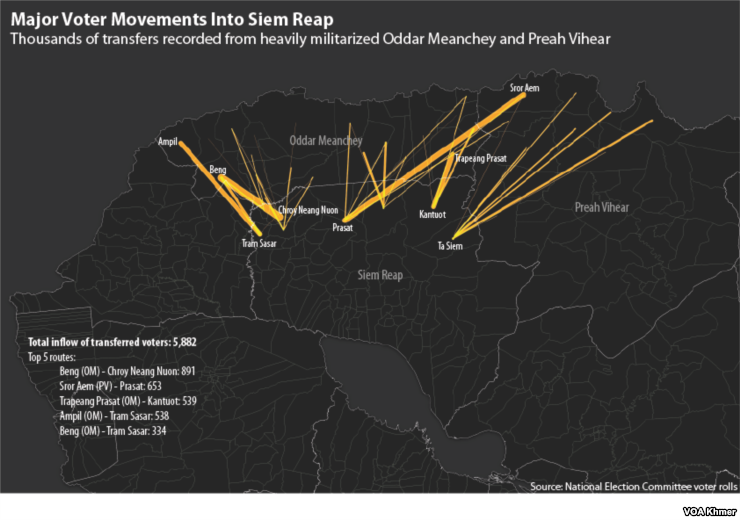

According to an analysis of the most recent National Election Committee (NEC) voter rolls, at least 5,882 new voters flowed into northern Siem Reap province in September and October from their previous homes in Oddar Meanchey and Preah Vihear, both sparsely populated provinces along the Thai border with a heavy military presence.

This graphic shows thousands of voter transfers recorded from heavily militarized Oddar Meanchey and Preah Vihear provinces to Siem Reap province in Cambodia. Data source: Cambodia's National Election Committee. (Michael Dickison/Julia Wallace for VOA Khmer)

There are six parliamentary seats up for grabs in Siem Reap, a large province in Cambodia’s northwest, while Oddar Meanchey and Preah Vihear have only one each. In the registration period that opened in September, Siem Reap province gained the highest number of new voters nationwide, nearly 42,000 people in total.

Siem Reap, like much of the northwest, was once solidly in the government’s camp, with the ruling CPP garnering 61% of the popular vote in nationwide local elections in 2012. But by the following year’s national election, it had fallen to 50%, edged out in many areas by the new CNRP, which was formed by a merger between two smaller opposition parties and galvanized massive support.

Ou Virak, a political analyst who heads the Future Forum, a local think tank, said the ruling party’s “serious drop” in popularity in Siem Reap was part of a broader phenomenon across Cambodia’s west, where many villages have been hollowed out by mass migration of young people seeking work in neighboring Thailand. Many of the farmers who remain are struggling with debt and low crop prices, while increasing access to information via smartphones and news from Thailand means that geographically isolated rural voters no longer reflexively vote for the CPP, Ou Virak said.

After almost being knocked out of power in 2013, the CPP scrambled to reestablish its dominance, ordering officials to “scrub themselves clean” of corruption and be more responsive to voters, while simultaneously cracking down on dissent. The party also established “working groups” to get out the vote in every province, headed by senior party figures. Despite an ostensible ban on politicking by military officials, the person placed in charge of the CPP’s efforts in Siem Reap was Defense Minister Tea Banh, a four-star army general.

In a speech in Siem Reap in May last year, General Banh told CPP members that they “absolutely must win the commune election.” Two weeks later, however, the CPP’s share of the popular vote in Siem Reap fell to 39%. The ruling party did manage to win the popular vote nationwide, but by just a hair above 50%.

In August and September, the CPP began taking steps that would lead to the formal elimination of its main political opposition. The CNRP’s popular president, Kem Sokha, was arrested on September 4, accused of colluding with the United States to overthrow the government. Finally, in mid-November, the CNRP was dissolved altogether by the CPP-stacked Supreme Court, and the government declared membership in the party illegal.

During the voter registration period, however, this outcome was still far from certain. What was clear was simply that the CPP was not doing as well as it had hoped to in Siem Reap and many other areas of the country.

Although it is not known precisely how many soldiers registered to vote in Siem Reap in 2017, there is evidence that thousands did. Of the nearly 6,000 voters who transferred from Cambodia’s border provinces into Siem Reap, 87.66% were men, compared to approximately 47% of registered voters nationwide. Several areas where the new arrivals registered are now heavily male. Nine polling stations in Siem Reap are over 95% male, including one station where 612 men and no women are registered, and another that registered the maximum 750 new voters but only three women.

Diep Yat, who was the deputy chief of Tram Sasar commune for the CNRP until the party was dissolved, said he personally witnessed hundreds of soldiers moving in from Oddar Meanchey to register there.

He said he had recognized some of them as members of his extended family and acquaintances who are members of the military.

“I asked them why they came to register here, and they said their boss ordered it. Before, they voted in a commune in Oddar Meanchey.”

Pang Sok is a former CNRP official in Klaing Hay commune, which also saw an unusually high increase in new voter registrations, around five times more than the national average.

Serving as an election registration observer, he said he witnessed several hundred soldiers and their families register in Klaing Hay, but when he attempted to report the alleged fraud to the National Election Committee, which is dominated by the ruling Cambodian People’s Party, he was brushed off.

On August 14, shortly before the soldiers began arriving in Tram Sasar, the NEC issued a declaration requiring local police chiefs to approve residential transfers for voter registration.

Most police chiefs are appointed by the ruling party, while commune chiefs, who had previously been in charge of the certification process, are democratically elected. The new rule allowed police officials like Eum Yun, who was appointed by the CPP in 1998, to gain control over the voter registration.

“I observed that the soldiers would come, go to the commune chief’s office, get a letter, immediately register to vote, and then go home,” Pang Sok said. “First the soldier would get a kind of letter certified by the commune police.”

He said some of the soldiers did not even know the names of the villages where they were registering as residents.

“I did ask the NEC about that and they just said, ‘This is the procedure. They have a letter,’ ” Pang Sok said.

“I was ordered to come here to protect people. I don’t know why.”

Hang Puthea, the NEC’s spokesman, confirmed that a number of soldiers had registered in Siem Reap, but denied this constituted electoral fraud. Instead, he said the military presence was necessary for “election defense,” echoing the term used by the commune police chief.

“There are some military registrations over there, but there are no irregularities,” he said. “We know that the Ministry of National Defense assigned them to register over there for election defense.”

He said he did not know the exact number of soldiers who had moved to register in Siem Reap, but doubted it was in the hundreds.

“Do you have the evidence or witnesses?” he asked. “You can show it to the NEC. Some people just said this.”

“I was ordered to come here to protect people. I don’t know why.”

An AK-47 assault rifle and camouflage accessories hang inside the makeshift military base camp in Srey Snam district's Tram Sasar commune on Dec. 21, 2017. (Sun Narin/VOA Khmer)

During a visit by VOA journalists to Tram Sasar commune in December, locals pointed out the location of the new military base, supposedly home to hundreds of people, in a forested area behind a school and a rice field.

There, in a clearing, an army wife was preparing a large cauldron of rice porridge for the soldiers based there. She said that there were only around 10 of them, not the hundreds of new residents the voter registration rolls would suggest.

“They came here during the election registration,” explained the woman, Tuon Sreylin, 34. “They just come in, come out, and around 10 people at a time stay here. The military register for voting here.”

Tuon Sreylin said that she, too, had been told to transfer her voter registration to Siem Reap, despite maintaining a permanent residence in Oddar Meanchey, where she had left her children with their grandparents.

“After the election we will go back,” she said.

In a wooded area nearby, a handful of soldiers were lolling in hammocks, napping or playing with their smartphones. Only their commander was sitting upright, tucking into a spread of Khmer stews and pickles at a desk in the compound’s main structure, a ramshackle building made mostly of corrugated metal. Behind him was the bed where he slept, decorated with Minnie Mouse sheets.

The commander of the military camp in Tram Sasar commune eats lunch on Dec. 21, 2017. “I was ordered to come here to protect people," he said. "I don’t know why.” (Sun Narin/VOA Khmer)

He declined to give his name, but confirmed that he was in charge of the encampment, and that the soldiers were stationed there “temporarily.” He said the number of soldiers in the area was confidential and could not be revealed.

“We came here to protect people and maintain social order,” he said. “I was ordered to come here to protect people. I don’t know why.”

At that moment, Commune Police Chief Eum Yun’s head popped out from behind a pillar, where he had apparently been hiding to observe the interview. Seeing that he had been spotted, he emerged. He had combed and slicked back his hair and donned his official uniform in the hour since VOA reporters had visited him at his own office, where he had been wearing rumpled plainclothes.

He told reporters that his “boss” had ordered him to follow them, determine whom they were speaking to, and bring them to the police station. There, they were extensively photographed and detained for around an hour. Finally, they were allowed to leave after being warned to cease conducting interviews in the area.

“We are afraid you came here to interview other political parties,” Eum Yun said.

A sign bearing the Cambodian People's Party logo and the faces of Prime Minister on the road to Tram Sasar commune in Srey Snam district, Siem Reap province. Dec. 21, 2017. (Sun Narin/VOA Khmer)

A sign bearing the Cambodian People’s Party logo and the faces of Prime Minister on the road to Tram Sasar commune in Srey Snam district, Siem Reap province. Dec. 21, 2017. (Sun Narin/VOA Khmer)

According to Cambodia’s Press Law, it is not illegal to conduct interviews with villagers or members of political parties, and prior permission from authorities is not required.

Pol Saroeun, the commander-in-chief of the Royal Cambodian Armed Forces, declined to comment on military voter registration or troop transfers.

“[What you] know, report. No need to ask me. I will not tell about this since you are not my boss,” he said.

His boss, Defense Minister Tea Banh, could not be reached for comment.

Ou Virak, the political analyst, said the CPP needed to focus on addressing the issues affecting voters in Siem Reap, rather than adding more of them. If soldiers are truly being brought into the province to register, the government risked alienating villagers even further, he said.

“In the short term they might be able to win the number, but if they continue this way they will not be able to win the hearts and minds of the people,” he said.

“Even if they don’t have the opposition to challenge them and there is no chance they will not win the election, at the end of the day they still need legitimacy and the mandate of the people.”

Pang Sok, the ex-commune official, said many of his constituents had observed soldiers registering to vote in their area, but could not do anything about it. He himself felt powerless, although he had an official position.

“I feel that it is unfair to the ordinary people,” he said.

“They just do whatever they want.”

This story originally appeared on VOAcambodia.com. (April 2, 2018)