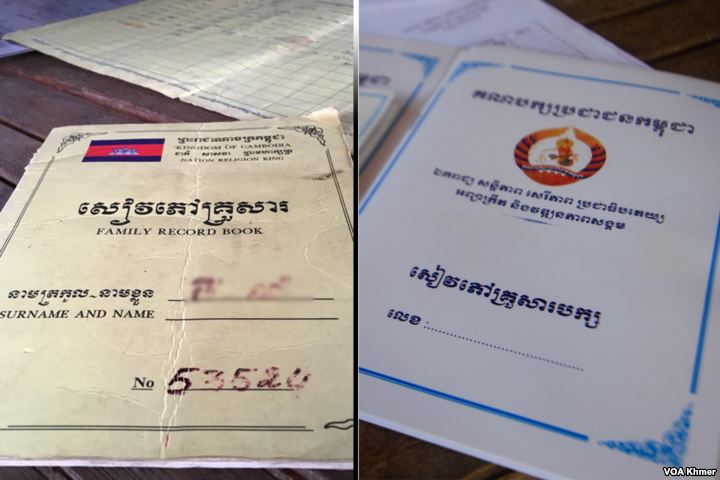

The "CPP family book" (right) registers party members in a family, while the "CPP group book" (left) assigns members to groups who will monitor each other's party spirit, Wednesday, November 8, 2017. (Sun Narin/VOA Khmer)

Community Stories

Cash, Oaths and Holy Water

Inside the CPP’s Quest to Identify Its Own True Supporters

Taches Commune, Kampong Chhnang Province This tiny, The ruling Cambodian People’s Party has seemingly never had a firmer grip on power.

It dominates government administration, the military and the judiciary, and has eliminated or outlasted all of its political opponents.

But its apparent supremacy masks a serious and growing problem: The more control the party exerts, the less clue it has about whether anyone truly supports it.

Here in Taches, a group of 15 rice-farming villages bisected by a new national highway, but beset by land conflict and hollowed out by emigration, Duch Thuon embodies the contradiction at the heart of the CPP’s might.

The 66-year-old used to support the ruling party, but a decade ago quietly transferred his allegiance to the opposition after becoming angered by government corruption.

Duch Thuon, 66, a villager in Taches commune, said he registered as a CPP member after being approached by local officials and feeling he had no choice, Wednesday, November 8, 2017. (Sun Narin/VOA Khmer)

But when his village’s deputy chief and a CPP-aligned councilor came to his home last month and asked him which party he would vote for, he knew the right answer.

“The party that gives life,” he told the visitors, using a politically correct term for the CPP.

Across the country, the ruling party has worked for decades to blur the boundaries between itself and the state. Projects paid for by state funds or external donors are often attributed to the CPP’s largesse. Thousands of schools are named after the prime minister. Villagers are told, repeatedly, that the party “gives life.”

An unintended consequence of this totalizing push is that citizens find it hard to reveal their true political preferences, given that military officials and local leaders who control access to state services are also party affiliates.

This can create the false impression that the CPP is universally liked—a balm to high-ranking officials’ egos, but one that complicates the fundamental business of democracy: actually winning elections.

“Because I live under their authority, when they came to ask, I just followed them. But in my mind, my heart, it is not that way,” Duch Thuon explained in an interview last week.

He grinned conspiratorially.

“I’m actually voting for the CNRP.”

“One Party Member, One Vote Supporting the CPP”

In response to disappointing results in June’s commune elections, the CPP has embarked on an ambitious new membership campaign to register entire households as “CPP families” and ensure that everyone who signs up is smos trong (ស្មោះត្រង់)—a Khmer term meaning “honest,” or literally, “straight and loyal.”

In other words, party administrators want to identify people who will actually tick the box for the CPP once they get inside the voting booth, which is increasingly the only place in Cambodia where true political inclinations can be expressed.

The rationale behind the drive was laid out in a party document circulated on June 7 and signed by Prime Minister Hun Sen. Three days earlier, on June 4, 3,540,056 people nationwide had cast votes for CPP commune councilors. But the party has 5,370,313 members.

FILE: Voters queue to cast their ballots in the fourth commune election, in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, in June 04, 2017. (Hean Socheata / VOA Khmer)

Hun Sen exhorted local officials to re-register supporters, this time making sure that each one of them would truly vote for the party. The campaign’s slogan is “One Party Member, One Vote Supporting the CPP.”

“It is since we lost two million votes, so we have to selectively choose for quality, which refers to people who are completely honest with the party,” party spokesman Sok Eysan told VOA.

Here in this part of Kampong Chhnang province, the registration drive has seen village chiefs go door to door asking residents like Duch Thuon to register for a new document called a “CPP family book.”

Confusingly, it looks similar to a key Cambodian state identity document also known as a family book. Unlike previous party registration cards, the book requires affiliates to provide photographs of their faces.

A Cambodian family book (left), a required government identity document, and a ‘CPP family bookÆ (right) registering party members in a family, Wednesday, November 8, 2017. (Sun Narin and Julia Wallace/VOA Khmer)

Those who register as “CPP families” are to be given a cash payment three times per year, according to documents viewed by VOA. However, they will also be expected to vote for the CPP, multiple local officials and villagers said.

Multiple interviewees told VOA that they felt pressure, implicit or explicit, to register for the document, or to agree to be included in their parents’ or husbands’ CPP family books, since the same local officials asking them to sign up were the ones responsible for processing normal identity and land ownership documents.

“There is confusion,” said Sun Kosal, a commune councilor for the opposition Cambodia National Rescue Party in Taches. “People are asking around: ‘What is it for?’”

Everybody interviewed said they were asked to thumbprint and add their photographs to a CPP family book by their village chief or deputy chief, even though village administrators are not supposed to engage in party politics. (The National Election Committee in May issued a circular reminding local officials that “the village chief and deputy village chief do not have the right to note or ask villagers about which political parties they vote for.”)

Village officials have been instructed to ensure that every “CPP family” genuinely supports the party, but they also report being under pressure by higher-level officials to boost the numbers of supporters on their lists.

This has resulted in some unusual efforts to ensure that those on the CPP family list show up in the polling booth in July and tick the party box.

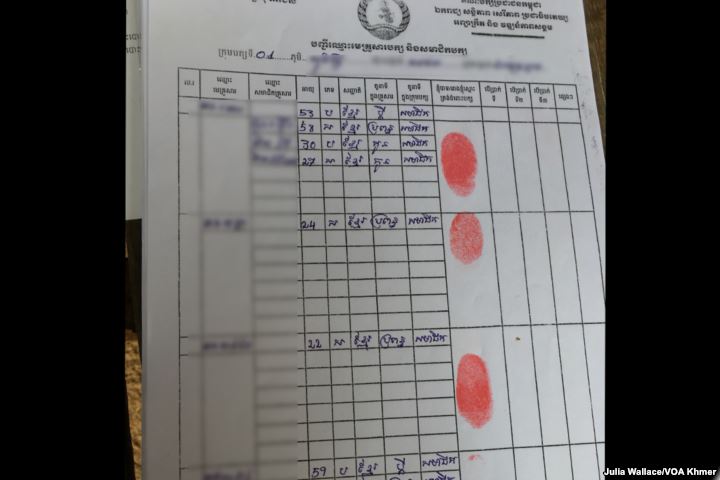

Everybody who signs up is also assigned to a “party group,” a cell of around 10 people who are assigned to monitor each other’s loyalty. Some village chiefs in Taches say they were told to make registrees swear an oath bringing death upon them if they did not vote for the CPP. In one case, a village chief went from house to house demanding that CPP registrees drink holy water to prove their loyalty.

“Why are you asking me a lot? Where are you taking this information to?https://projects.voanews.com/cambodia-election-2018. Honestly speaking, VOA and RFA are part of the structure of the color revolution. If you follow them it is up to you.”

FILE: Sok Eysan, a spokesman and lawmaker of the Cambodian People's Party, gave an interview to VOA in his office at the CPP's headquarters in Phnom Penh, October 12, 2016. (Hean Socheata / VOA Khmer)

CPP spokesman Sok Eysan said that although the registration drive was a national initiative, provincial officials were given latitude to implement it differently. He said swearing oaths, drinking holy water and paying new members were not official party policy, but they were allowed.

“It depends on the ability of each provincial head,” Sok Eysan said.

In an indication of how sensitive the issue is, the party spokesman cautioned a VOA reporter that asking detailed questions about the registration drive might be a sign that the journalist was supporting a “color revolution.”

“Why are you asking me a lot? Where are you taking this information to?…. Honestly speaking, VOA and RFA are part of the structure of the color revolution. If you follow them it is up to you.”

“Are You With the CPP? Gold Is Not Frightened of Fire”

Before the June elections, the chief of Boeng Kak village in Taches took a straw poll. The responses indicated that the CPP would win the vote, but in the end the opposition took the village by a margin of around 80 votes.

That is why identifying smos trong CPP supporters is so important, said Nget Vanna, a former soldier who became village chief around five years ago.

In a quest to do so, he instituted a “water pledge.” After registering villagers for the CPP family book, he asked a Buddhist monk to bless a large bottle of water and toted it from house to house, testing those who had professed support.

“If you love other parties, we don’t say anything, just walk away,” Nget Vanna said. “But if you say you are CPP and you will vote for CPP, do you dare to swear? Do you dare to drink the oath-taking water? This is for honesty since some tell lies just for gifts.”

The oath-takers were asked to swear that if they did not vote for the CPP they would meet with death and destruction, he said. They were allowed to choose their own form of calamity.

“They swore by themselves, including [dying] while walking, getting a snakebite, getting into a car crash, and Buddha destroying them,” he said.

For Nget Vanna, there is nothing problematic about asking people to swear fealty to the party. He said nobody was pressured to sign up in the first place.

“We just want to know, are you sure with the CPP? If you are with the CPP you are not afraid. Gold is not frightened of fire.”

Nget Vanna said that after villagers drank the water and swore allegiance, they would have their CPP family book formally registered and receive three cash installments of $12.50 each, starting next year. In the past, he said, party supporters received small gifts, but not money.

This CPP document from Kampong Chhnang province, pictured in this November 8, 2017 photo, lists names of registered party members who will be given cash payments three times next year. (Julia Wallace/VOA Khmer)

The first payment is scheduled to be made in April 2018, three months before the national election in July.

Out of 437 eligible voters in Boeng Kak village, 166 drank the holy water. Mr. Vanna said he would expect every one of those people to be “honest” and deliver a vote to the CPP.

But what does it mean to be honest in a rural village where everyone knows your name and professed party affiliation?

Long Savoeun, a 65-year-old Christian pastor, is sick and frail, but recalls being visited by Mr. Vanna and his deputy, along with a third village official.

“The village chief just said, ‘If you are gold, if you are not afraid of fire, if you vote for the CPP, dare to take the water,’” he recalled.

Confronted with the demand to swear allegiance, Long Savoeun was distressed, partly because he felt it might be un-Christian. Ultimately, he said he drank the water but declined to take an oath, citing his religious beliefs.

“After they left I discussed it with other villagers, and they said it’s not necessary to drink the water and it’s up to us which party we vote for,” he said.

As Long Savoeun was being interviewed, the village chief drove by his home and parked at a house nearby. Long Savoeun trailed off. He said he preferred not to discuss his political preferences.

Falsified Preferences: “I Didn’t Refuse Them, Because I Was Afraid They Would Watch Me”

A short drive down National Road 5 from Boeng Kak village lie the neighboring villages of Banteay Meas and Sovong, where the registration drives were in full swing for most of October.

In Banteay Meas, the CPP beat the CNRP by just one vote in the June commune elections, a fact that everyone here seems acutely aware of.

Sun Kosal, the opposition commune councilor, said that although savvy villagers understood that registering for a CPP family book was a way of joining the party, others were confused.

Once they signed up, he noted, they would be incorporated into the CPP “group book” system, and other party members would go to greater lengths to enforce politically correct behavior.

“Some people will follow the CPP because they don’t understand much and are easily forced to join the party,” he fretted.

Down the road, the Banteay Meas village chief, Nguon Korn, was relaxing at his home, which doubles as a small convenience store. Several large signs promoting the CPP were stacked against a wall just inside.

He confirmed that he had gone door to door asking villagers to sign up as party members, but insisted he put no pressure on them.

“I know as a village chief we have to be neutral, but we just want to know who supports the CPP,” he said.

“Honestly, the intention is to find the true supporters who truly support the CPP. We just want to look for people who are honest with the party.”

But in rural Cambodia, that is easier said than done.

Villagers will often go to great lengths to stay on good terms with their commune and village chiefs, according to Caroline Hughes, a professor at the University of Bradford in the UK, who specializes in Cambodian politics.

Doing so “ensures that they will be considered, even consulted, in commune-level decision making about local development issues,” she wrote in a 2013 paper.

“They will be invited to participatory planning meetings and included in distributions of resources and gifts from commune patrons. Most importantly, if they have a problem—a reversal of fortune or a serious dispute—they will be able to get a degree of support.”

But in exchange for such help, Hughes writes, villagers must show loyalty. Because local officials are responsible for routine document processing, it can be difficult to openly deny them when they ask for a thumbprint.

Duch Thuon, the opposition supporter who registered for a CPP family book, felt he had no choice but to go along with the process.

“I just gave it [my thumbprint] to them because I live under their authority,” he explained. “I know they were forcing me to join their party.”

He was aware that if he agreed to join, he would make his life easier—and be put on a list to receive cash next year.

If he refused, he expected to be watched and harassed, which he claimed had occurred to opposition supporters during the last election.

He said there were rumors that government officials would be using cameras to monitor polling stations in 2018 so they would know if any registered CPP family book holders did not vote for the ruling party.

In the neighboring village of Sovong, a man named Mey Chham said he had been directly warned of poll cameras by the trio who visited him asking him to register for the CPP: his village chief, the deputy village chief and a third village official.

“They said, ‘If you give your photos and ID card and then vote for the other party, they will know because they have a camera.’”

Mey Chham, 69, a resident of Sovong village in Taches commune, was uncomfortable telling his village chief he did not want to join the CPP when she came to his house and asked for photographs of each of his family members to register them in a CPP family book. (Sun Narin / VOA Khmer)

He said he was visited twice by the officials, once soon after the election and again about two weeks ago.

“They said, ‘If you give your photos and ID card and then vote for the other party, they will know because they have a camera,’” said Mey Chham, a wiry 69-year-old farmer who has only just started feeling too old to clamber up palm trees to collect their sugary sap.

He knew he did not want to become a registered CPP supporter. He was also afraid to directly inform his village chief and deputy chief—the two most powerful local officials—that he did not support their party. So he fibbed.

“I didn’t refuse them, because I was afraid they would watch me,” Mey Chham said. “I just said I had no photos.”

A Village Chief’s Dilemma: “I’m Just Waiting to be Blamed”

Across National Road 5 from Mey Chham’s house, his village chief was sitting at home—anxious, in turn, about those who are watching her from above.

Seum Yun, a voluble 63-year-old grandmother, earns $50 a month as the head of Sovang village, a job that is increasingly seeming like more trouble than it’s worth.

Seum Yun, 63, is the chief of Sovong village and has been tasked with registering residents for the CPP family book. “We don't know if they feel pressure or not, but we don't force them to sign,” she said, Wednesday, November 8, 2017. (Sun Narin/VOA Khmer)

She oversees local charity efforts, like a sanitation system paid for by an NGO that is being planned out by a group of young staffers at her house this week. She is responsible for village administration. And then there is the work she is expected to do on behalf of the CPP—despite holding an ostensibly apolitical position.

“Party work is busier than state work!” she exclaimed, gesturing dramatically with one hand as she used the other to feed grains of rice to a blind chicken on her lap, one of several animals in her compound that she dotes upon.

The hardest thing, at the moment, is the CPP registration drive, which she had been working on for three months.

“It’s a lot of work. I need to walk into houses day and night, asking people for photos, and for this work I don’t get any money,” she complained.

“I’m so sick of it. I have to walk and get into houses, from house to house, and sometimes it’s not just one time, but two times, three times, checking if they are really honest with the party.”

She said village chiefs in the area were all aligned with the CPP and had been advised by party officials to make villagers swear oaths. Seum Yun, however, was doubtful that this would succeed.

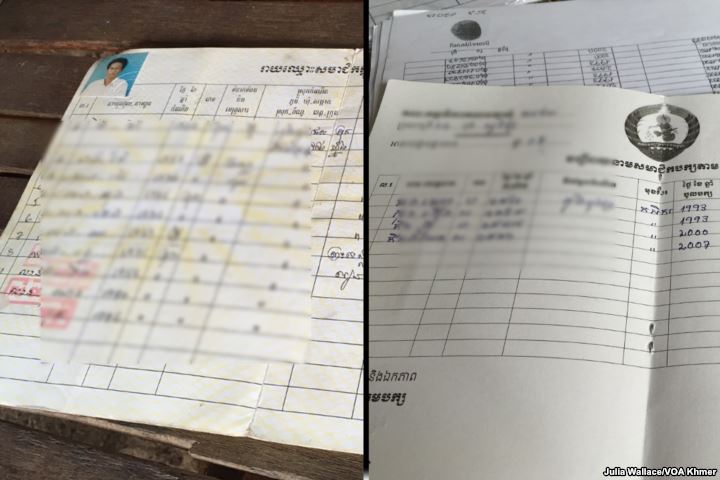

The government's family book (left) and CPP family book (right) have similar layouts, listing names of parents and children, as pictured Wednesday, November 8, 2017. (Julia Wallace/VOA Khmer)

“The party advised people who signed their name to pledge to vote for the party or get a car crash, get hit by lightning, but I don’t do that with my people. This was said in the committee meeting,” she explained.

“There is a concern—they want genuine supporters, to select people who will really vote for the CPP. We don’t know. That’s why they want people to take an oath.”

She insisted that no villagers were pressured to register—but cheerfully admitted that once they did, they would be considered honor-bound to vote for the CPP.

Her own position is on the line. Her bosses in the party are simultaneously telling her to collect more members and to make sure registrees are “honest.”

“If those people we collected do not really vote for the CPP, those people [higher-level officials] will blame me,” she said.

“But they asked me for more people, and it’s above my ability. I’m just waiting to be blamed.”

Taches commune has struggled in recent years with a high-profile land dispute pitting a group of determined smallholders against the powerful wife of the Mines and Energy Minister. There is also a sense of despair at the emptying out of villages as young people migrate to Thailand or take jobs in the garment factories surrounding Phnom Penh.

In the June elections, the CPP lost five of the commune’s 15 villages, and for the first time four opposition party members sit on the Taches commune council. Seum Yun said she knew there were more CNRP supporters in her village than true CPP believers, and feared her job was on the line.

Mey Chham and his wife, Neang Mai, said so many youth had departed the village for Thailand or factories near Phnom Penh that a new joke was going around: “Now it seems like old people are having babies again.”

As they spoke, they dandled and soothed their fretful 2-year-old grandson, Samnang. Their children, too, are all away.

Making a Younger Generation of Voters ‘Legible’

It is partly these new patterns of migration and urbanization that have led the CPP to its current quandary.

Intensive local-level surveillance, subtle intimidation and vote-buying are not new tactics; in fact, they are partly how the CPP has kept the country in its grip for so long.

But what is different now is the competition and the electorate. In 2013, for the first time in years, the CPP was up against a united opposition party that has a compelling message and widespread popular support. At the same time, Cambodian voters are increasingly young, mobile and sophisticated, rather than older peasants grounded in the rhythms of village life.

“They said, ‘If you give your photos and ID card and then vote for the other party, they will know because they have a camera.’”

Children ride their bicycles past a sign bearing the Cambodian People's Party logo and the faces of Prime Minister Hun Sen and National Assembly President Heng Samrin in Banteay Meas village, Taches commune, Kampong Chhnang province. Although village officials are supposed to be politically neutral, the chief of Banteay Meas is registering villagers as CPP members. “We just want to look for people who are honest with the party,” said the chief, Nguon Korn. (Sun Narin / VOA Khmer)

Hughes noted that despite its vast local networks, the CPP was taken aback when it nearly lost the 2013 national election.

“This is significant because it suggests that these sophisticated and well-practiced techniques of social control are not working as well as previously in rendering the electorate legible to the party,” she writes.

She attributes the party’s overconfidence partly to demographic and economic change, which has brought young Cambodians to cities to be educated or sent them to Thailand as migrant laborers, disrupting traditional household and village structures and feeding them new ideas about governance.

While many local officials continue to have a clear idea of how older people will vote, they often find themselves stymied by the younger generation.

This may explain why the new registration campaign revolves around family groups. The June CPP circular signed by Hun Sen says it “urges the expansion of new members, especially youth, to support the party so the party can win next year’s election.”

In Kandal province’s Takhmao City, village chief Hang Savoeun, 57, said she generally had a clear idea of how older people would vote, but not their children.

“Their parents are CPP and when we go to ask for the photos, their parents give, then we also meet the young people and they allow us to take photos,” she said.

Hang Savoeun said she did not personally believe in oaths, but tried to gauge families’ true affinity for the party by how friendly they were during their interactions and how positive toward the CPP they acted generally.

“Only words do not prove anything, but we also observe them, their actions,” she said.

In Phnom Penh, an educated professional in his early 30s named Ty said that his mother, who is 69, was well-known to local officials as a regular CPP voter.

“She thinks the CPP brought peace and makes people do business well,” he explained. “She is also afraid of war.”

Aware of this, a CPP commune official stopped by their home and said she would register the entire family into a CPP family book.

The official already knew the names of everybody in the household and promised a payment of $12.50 if they signed up.

Feeling pressure, Ty, who asked to be referred to by a nickname for fear of reprisals, agreed to thumbprint the book along with his wife and his sister. But he feels no commitment to the CPP.

Unlike his mother, he is not afraid of war, and in the commune election he voted for the opposition party. This time around, he plans to watch and wait before choosing a political side.

“I am still observing the political situation,” he said. “I will decide on Election Day.”

This story originally appeared on VOAcambodia.com. (November 15, 2017)