The Economic Toll of the Underage Marriage Market

Child marriage stops education, limits earnings potential

Child marriage exacts a heavy toll, not only on girls and their families, but also on their countries, says Quentin Wodon, a lead economist at the World Bank.

“Child marriage has major negative implications for the rights of girls to safety and security, to basic health, to going to school and to be able to make their own decisions in life,” Wodon says. As for consequences to the country, early “marriage has major negative impacts for poverty reduction and for economic growth.”

Wodon is co-author of “Economic Impacts of Child Marriage,” a 2017 study by the World Bank and the International Center for Research on Women that looks at 25 developing countries.

Child marriage typically halts a girl’s education, limiting her lifetime earning potential and her country’s productivity, researchers found. Girls who marry early have more children and health risks. For those countries collectively, the overall cost of failing to curtail child marriage by 2030 could reach trillions of dollars, the report concludes.

VOA talked to Wodon at the World Bank’s headquarters in Washington, D.C. The economist, who also holds doctoral degrees in theology, health sciences and environmental sciences, has long focused on poverty, and he now looks at its interplay with education and early marriage.

He emphasizes the need for policymakers to make sure families have viable alternatives. The best bet, he says, is extending girls’ education beyond the primary level. The study found that the likelihood of a girl marrying early falls by at least 5 percentage points for every year of secondary school she completes.

Wodon urges more use of proven interventions. The goal is to reach a tipping point in which families recognize the benefits of, and opt for, delaying unions. Normalizing that behavior, he says, “shifts the dynamics of the marriage market.”

The interview has been edited for clarity and length.

VOA: How extensive is child marriage around the globe?

QW: The situation is very different depending (on the location). In South Asia, we’ve had a very large decline in the prevalence of child marriage — the share of girls marrying before 18 — over the last two decades, especially thanks to India. In Africa, you had a very slow decline, but still more than a third of the girls marry before 18. In Latin America (and the Caribbean), the incidence apparently has gone up slightly. Globally, it remains a very serious issue.

Global perspective

| 10% | 20% | 30% | 40% | 50% | 60% |

Why is this still such a persistent issue?

Most girls who marry before 18 do so because there’s a lack of viable alternatives. The best alternative is to keep the girls in school. But it’s not always feasible. The schools may be far away, too costly to attend or of low quality, which means that parents will have a hard time making the financial sacrifices that are necessary for the girls, and the boys, to remain in school. It’s not that parents do not want to do the best for their daughters. They do. But often, there is no alternative. That may lead parents to marry off their daughters at a young age. Parents are trying to protect their daughters, actually.

How do you look at the costs?

The largest cost is related to fertility. If you marry early, you are going to have, on average, more children over your lifetime. And that has huge implications in terms of poverty rates and in terms of GDP per capita. If you have many more mouths to feed in your household, that would lead to lower levels of consumption per person. You’re going to be poorer. The second largest cost is earnings. Marriage is not the only reason why girls drop out of school, but it’s certainly the most important reason. In many countries, 20% to 30% of girls who drop out do so because of marriage or pregnancy. When girls have lower levels of education, they tend to earn much less in adulthood. They don’t have access to the same jobs. They’re not as qualified.

How do you explain to ordinary people the economic benefits of delaying marriage past childhood?

The question is whether conditions are there for economic benefit. In some countries with the highest incidences of child marriage and early childbearing, there are few opportunities for girls who would complete their secondary education to have good jobs. I do believe that in many cases, parents do want a girl to have the best education that she can get.

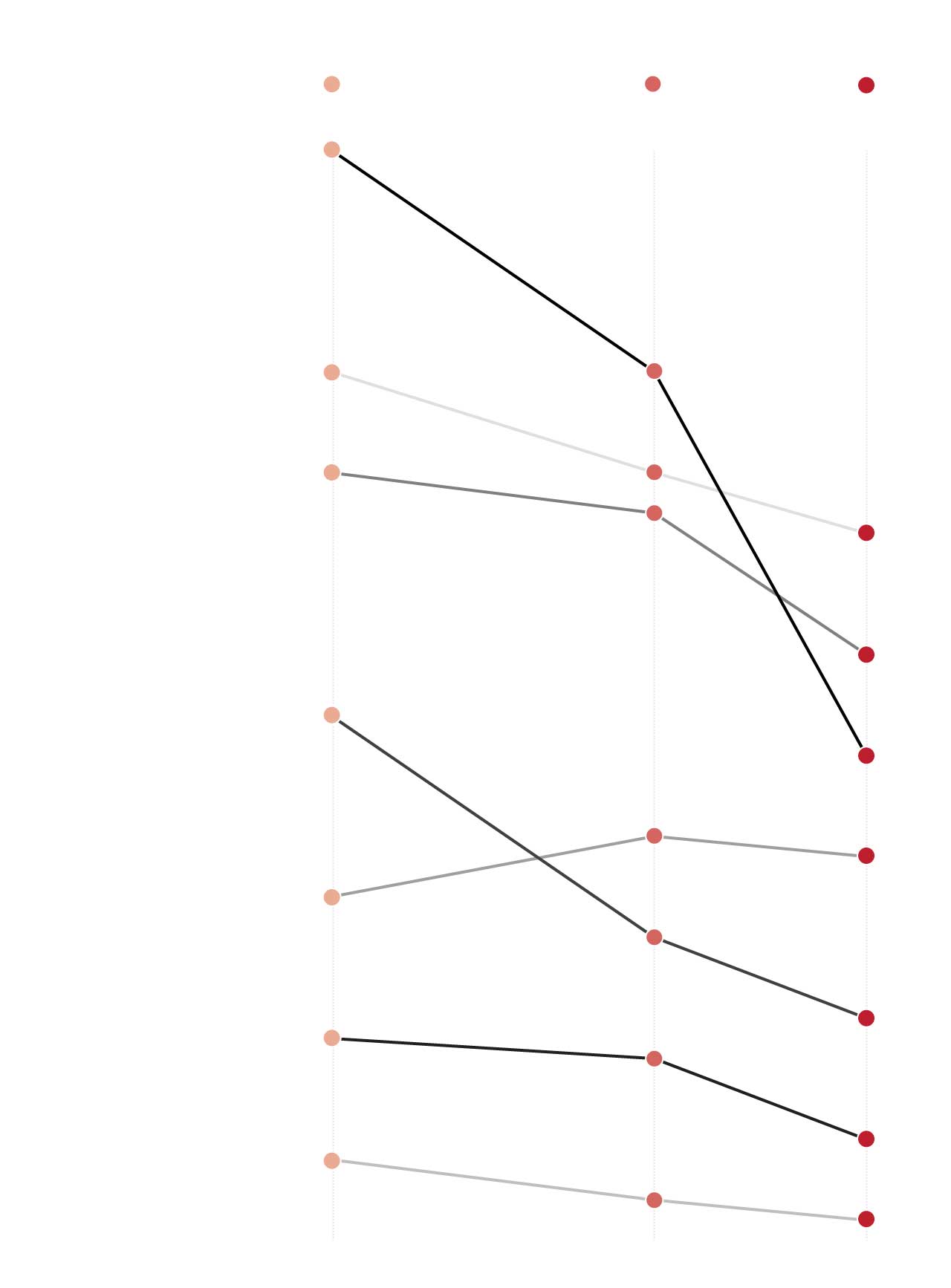

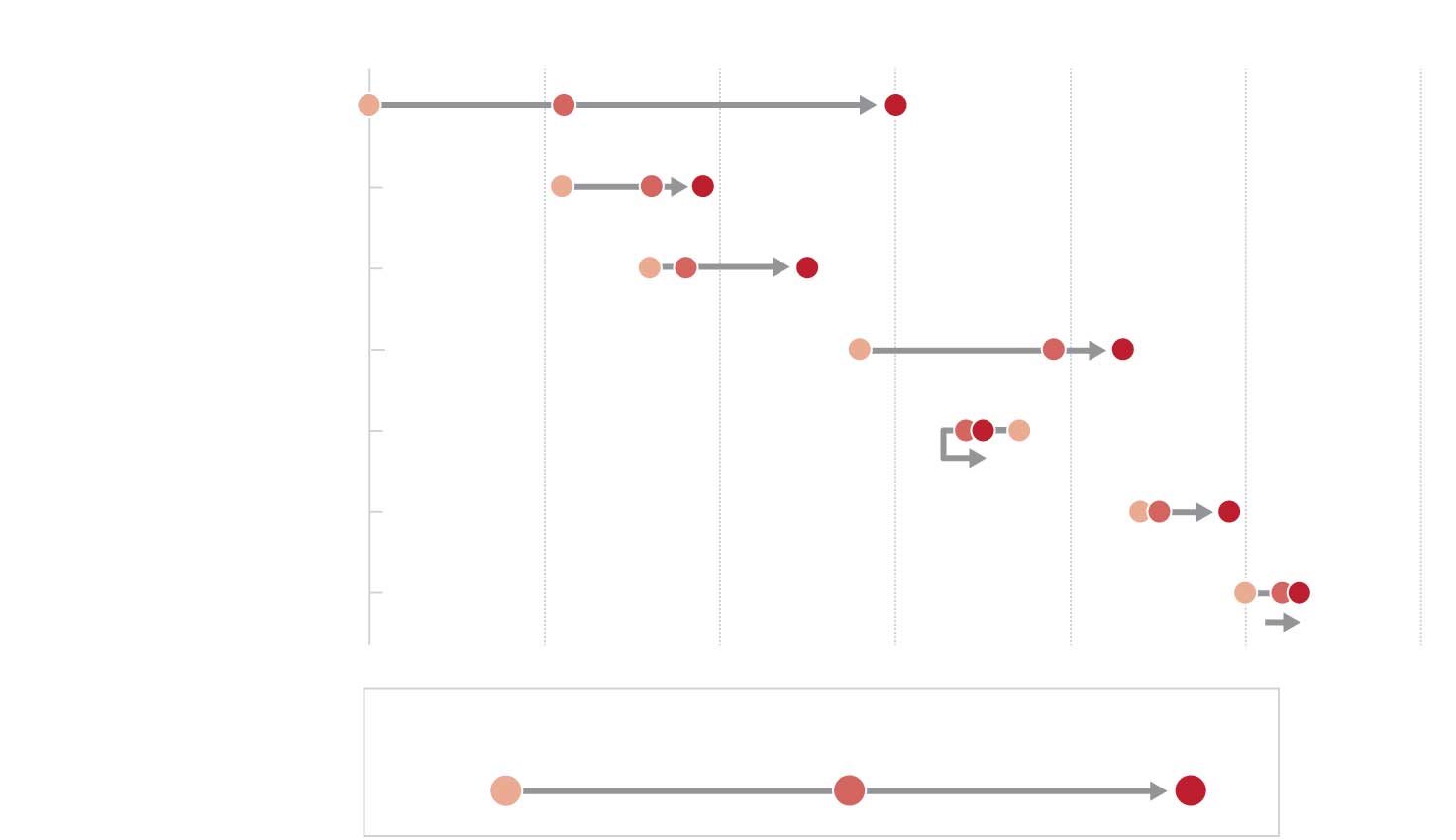

The changing percentage of women aged 20-24 years who were first married or in union before age 18, by region:

| Region | 25 years ago | 10 years ago | Today |

|---|---|---|---|

| South Asia | 60% | 49% | 30% |

| West and Central Africa | 49% | 44% | 41% |

| Eastern and Southern Africa | 44% | 42% | 35% |

| Middle East and North Africa | 32% | 21% | 17% |

| Latin America and Caribbean | 23% | 26% | 25% |

| Eastern Europe and Central Asia | 16% | 15% | 11% |

| East Asia and Pacific | 10% | 8% | 7% |

25 years ago

10 years ago

Today

South Asia

60%

West and Central Africa

49%

Eastern and Southern Africa

44%

41%

35%

Middle East and North Africa

32%

30%

25%

Latin America and Caribbean

23%

17%

Eastern Europe and Central Asia

16%

11%

East Asia and Pacific

10%

7%

60%

50%

40%

30%

20%

10%

0%

South Asia

West and Central Africa

Eastern and Southern Africa

Middle East and North Africa

Latin America and Caribbean

Eastern Europe and Central Asia

East Asia and Pacific

25 Years ago

10 Years ago

Today

Source: UNICEF

You mentioned a decline in child marriage prevalence in South Asia. Are there any other reasons for optimism?

In quite a few countries, you’ve had a large decrease over the last 20 years or so. Niger has the highest rate of child marriage in the world. But the Niger government is actually very interested in finding ways to reduce the prevalence of child marriage. In the West African country of nearly 20 million, 76% of girls marry by 18. Ending child marriage and early births would reduce its projected 2030 population by 5%, the World Bank/IRCW report found. There has been a shift in many countries with a realization that it is feasible to reduce dramatically and, hopefully, end child marriage, and the benefits would be very, very large for the countries.

How much do laws and policies matter?

Laws are not always enforced for random reasons in the developing world. About two-thirds of child marriages happen below the legal age. And this just points to the fact that laws are not enough. You need all those interventions on the side.

Girls take a break at Loreto secondary school, July 30, 2017, in Rumbek, South Sudan. The region's only all-girls boarding school requires a signed promise by each girl’s guardian not to remove the child from school until her graduation. (Photo by Mariah Quesada for AP)

You’ve talked about reaching a tipping point in social norms. Please explain.

Imagine that you have a pot of money — for example, cash transfers for girls to be in school or reduced fees. You could provide a little bit everywhere in a country, or apply it to an area with an especially high rate of child marriage. It’s important, when you have limited funds, to go in a concentrated way to those hot spots. … In some of the interventions, at the local level there is a shift where many girls would stay in school. Sometimes, you see a shift then in the local marriage market that enables other girls to get married later because the norm is not the same anymore.

How has your research affected your thinking about child marriage?

Before I got involved in this work, I knew that investing in girls’ education was important. But this whole research project and the findings that we got have convinced me that this is truly one of the best investments that countries can make.