Part 2

Trek North: Coming to America on Foot

A growing number of Chinese migrants in recent years have traveled thousands of miles to South America, where they begin a dangerous trek to the United States. Their journey begins in Ecuador and through Colombia, and then the long route north through Panama, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras and Guatemala in Central America. The final leg of the journey is Mexico, where the route leads to the U.S. border toward their American dreams.

After crossing the U.S.-Mexico border while still walking on an abandoned bridge, Yulong Shen heard police sirens from behind.

He wasn’t afraid. He had finally reached his destination, and he felt safe.

“We walked all the way through Central America, where the crime rates are really high. We were mugged by the police and by drivers along the way. So, I actually felt safe the moment I stepped foot on American soil,” Shen told VOA Mandarin on a bench in New York’s Central Park. He has been in the U.S. for eight months.

For 5-year-old Xiao Chen, walking to America was adventurous, to say the least.

Chen Xiao, 5, came to the U.S. with her parents in the summer of 2022. When asked what would happen if she hadn’t held tight while climbing the U.S.-Mexican wall, she said, “I will die.” (VOA)

“When I was climbing the [border] wall, I couldn’t hold on to it. But a guide caught me. Otherwise, I would have fallen down,” she told VOA at her family’s home in San Francisco.

Her father, Xu Chen, recalled the wall was about 6 or 7 meters tall. He said his wife, Chunmei Liu, was pale when she finally made her way down the wall.

The family of three were then taken by the U.S. Customs and Border Control Agency.

“Their van had hard seats, but I still thought it was comfortable. We’re finally at our destination,” Chen said.

The path north

For many Chinese migrants seeking to enter the United States illegally, the path begins in Ecuador. With few possessions, they go through Columbia, Panama, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras, Guatemala and Mexico, before finally arriving at the U.S.-Mexico border.

According to U.S. Customs and Border Protection, 2.4 million illegal immigrants were intercepted at the U.S.-Mexico border in fiscal year 2022. At least 853 people have died during the trek north, a record high.

In recent years, growing numbers of Chinese migrants are taking this dangerous route toward their American dreams.

“Mainly because China’s economy is slowing down,” said 37-year-old Fei Yang, who uses a pseudonym to protect his identity. “I was in e-commerce selling sports goods online. Things got worse year by year. At first, the revenue was several million RMB [renminbi]. Then it became 1 million. And later, it’s several hundred thousand,” he told VOA.

“The narrative that only the Communist Party can save China. .... I don’t want them exposed to that.”

“China as a country is rich, yet its citizens are poor,” he said.

Yang’s family of four spent time in Thailand and Africa before deciding to come to America. He said one of the reasons he emigrated was because he didn’t want his two children subjected to brainwashing by the Chinese government.

“The narrative that only the Communist Party can save China,” he said. “I don’t want them exposed to that,” he told VOA in a phone interview.

After arriving in Mexico, the family bought a scooter for $800 dollars, rode it for 11 days — roughly 2,400 kilometers — before arriving in the United States.

Xu Chen also didn’t want his daughter exposed to the so-called patriotic education in China. His small business crashed during the COVID-19 pandemic, and he couldn’t see himself migrating during school and work.

He didn’t know what to do until May 2022, when he learned it was possible to walk to the United States. After joining a group on Telegram to better understand emigration logistics, the family started their journey three months later.

It took Yulong Shen 5 months, traveled 8 countries to arrive in the U.S. (VOA)

Legal, illegal migration

“Actually, Ecuador was a transit point of illegal Chinese immigrants some 20 years ago,” a Chinese immigration agent who requested anonymity told VOA. “Later, the line slowly died down, mainly because Chinese people can apply for U.S. visas quite easily,” he said.

For the past 20 years as the U.S. and China deepened bilateral economic ties, growing numbers of Chinese citizens legally entered the U.S. through school or work. But things have changed in the past five years. Deteriorating U.S.-China relations, the COVID-19 pandemic and China’s strict border control convinced some Chinese dissidents that this could be their last chance to get out.

The immigration agent told VOA that so far this year, between 30 to 100 Chinese migrants checked into hotels in Quito, Ecuador’s capital, on a daily basis — most of them were preparing to travel to the U.S.

“The more you restrict people, the more they want to get out,” he said.

‘Anti-government rebels’

Shen was a member of a WeChat group that in his words, consisted of “anti-government rebels.”

“There were a few hundred of us. Now, all of us have come [to the U.S.] via various routes,” he told VOA.

The 37-year-old loves rock music. In China, he was a guitar teacher by day and a guitarist at a bar by night. After President Xi Jinping came to power, Shen found there was less freedom of speech, half the bars had closed down, and Communist Party flags were at the entrance of his village.

He criticized the government on WeChat and was summoned by the police. His social media account was shut down, and banks refused to issue him a debit card. He couldn’t afford a condo. He couldn’t afford to be sick. And he had no freedom to speak his mind. To him, his life in China was hopeless.

He left the country in July 2021, but the journey was not easy.

He flew to the Bahamas, about 400 kilometers south of Florida. There, he united with a dozen migrants, and together they spent $50,000 for transportation on a sailboat named Exodus. The plan was to sail to America like the pilgrims on the Mayflower and seek asylum in Florida.

“He told me that we would be sent to Cuba, and then the Cuban government would facilitate the deportation. I was devastated. I know Cuba and China are similar — both have authoritarian governments.”

“We didn’t examine the sailing conditions in the Bahamas and just set off, thinking that we would just head north to the United States. But we were grounded as soon as the tide went out,” Shen said.

They were stopped by the Royal Bahamas Defense Force, which Shen said was the most anxious part of his journey.

“What I feared most was that I would be deported back to China. I [asked] a guard if I would be deported. He said yes. I asked what the route was. He told me that we would be sent to Cuba, and then the Cuban government would facilitate the deportation. I was devastated. I know Cuba and China are similar — both have authoritarian governments,” he said.

Shen sought help online, and the group caught the attention of the media and some human rights organizations. With their help, the Bahamian government set them free after a few months.

‘What I was looking for’

Shen and another migrant went to Quito and planned their journey to America on foot.

“The most difficult part is the rainforest in Panama. You feel like it’s impossible to walk out of it. It’s extremely hot, and it’s all mountainous roads. You are basically in knee-high mud all the time,” he said.

Trekking in the rainforest between Columbia and Panama, Yulong Shen onced felt desperate. “I felt it’s impossible to walk out of it,” he said.

Most of the migrants who talked to VOA said the rainforest was the most dangerous part of their journey.

Yang told his six- and 4-year-old children that they were having a jungle adventure.

Liu said she still couldn’t believe her family walked through the forest together.

After five months and eight countries, Shen arrived in America on December 19, 2021, and stayed at four immigration detention centers before being released and going to New Jersey. He has filed for political asylum.

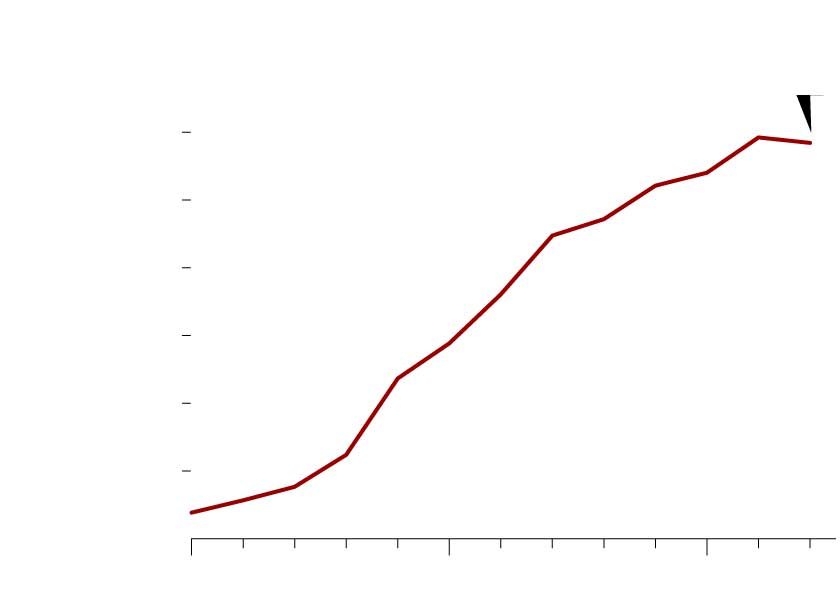

2022: 116,868

120,000

100,000

80,000

60,000

40,000

20,000

2010

2015

2020

2022: 116,868

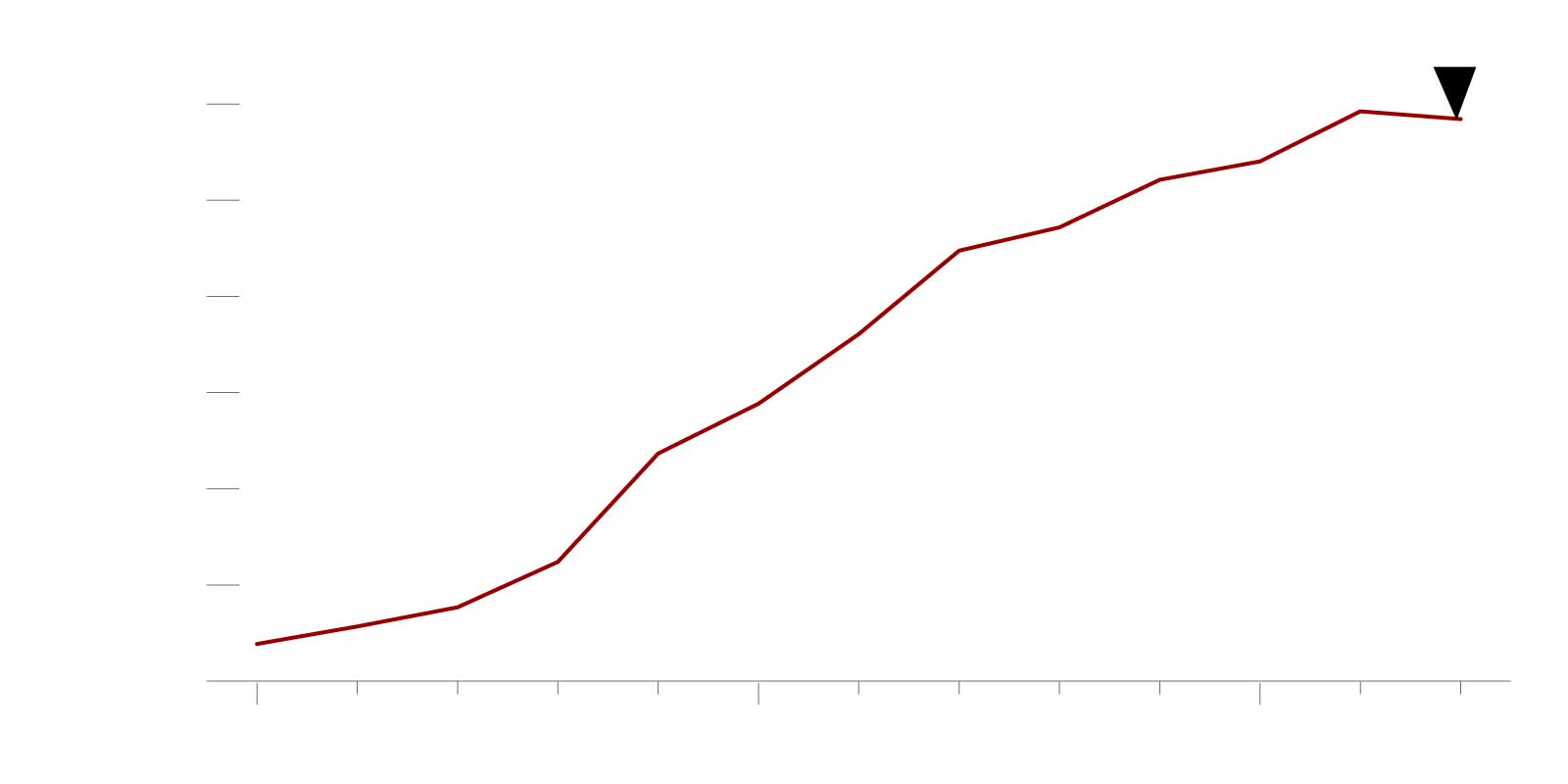

120,000

100,000

80,000

60,000

40,000

20,000

2010

2015

2020

2022: 116,868

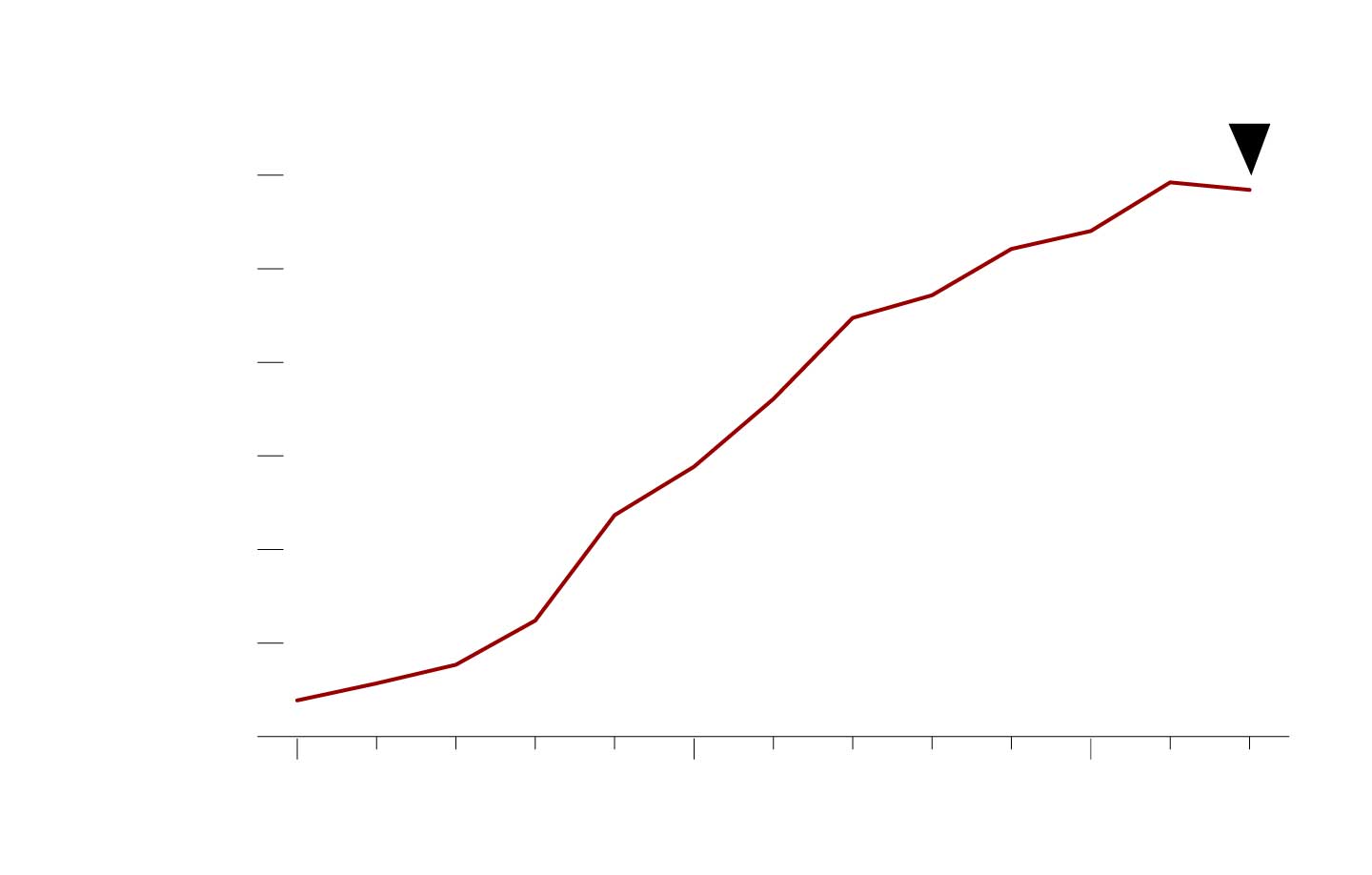

120,000

100,000

80,000

60,000

40,000

20,000

2010

2015

2020

UNHCR statistics shows, the number of Chinese seeking asylum overseas has increased 14-fold in 13 years. (VOA)

According to data from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, the number of Chinese people seeking asylum overseas has increased from 7,732 in 2010 to 116,868 in 2022. The number has increased 14-fold in 13 years, with most of that growth occurring after Xi became president.

Shen doesn’t regret his arduous journey.

“[The U.S.] is not a perfect place. But the thing is, you have freedom. You have freedom of speech. You have freedom to make choices. This is exactly what I was looking for,” he said.