China Sends Scientists to Key Arctic Outposts After Research Setbacks

After lengthy absences, Chinese scientists paid visits to outposts in Norway and Iceland, arctic researchers tell VOA.

A photo of China Iceland Arctic Research Observatory research building in Karholl, Iceland, as published by Chinese state news agency Xinhua. The image is dated Oct. 18, 2018, but VOA could not verify its authenticity.

Beijing is trying to recover from years of setbacks to its scientific, land-based projects in the Arctic, by sending personnel to two outposts that are vital to its goal of establishing China as a “near-Arctic” state.

China’s Arctic policy document, published in 2018, said scientific research to “explore and understand” the Arctic is the “priority and focus” of Chinese participation in Arctic affairs. It said that participation will involve “Arctic-related cooperation … with all relevant parties … under the Belt and Road Initiative,” China’s global infrastructure development program marking its 10th anniversary this year.

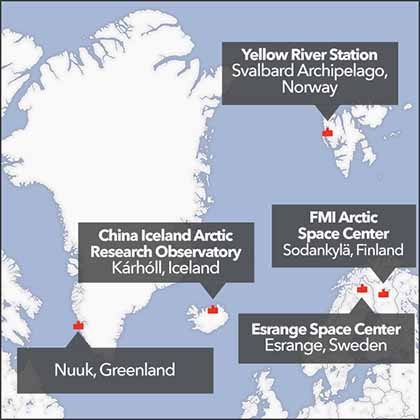

Over a 14-year period beginning in 2004, China launched scientific projects in the Arctic regions of four western European nations with their approval — Norway, Iceland, Sweden and Finland — and it sought to do the same in a fifth, Denmark’s autonomous island of Greenland.

China's projects in the Arctic

Another goal of China’s Arctic policy is economic. It seeks cooperation with other nations to jointly build a “Polar Silk Road” that will open the Northern Sea Route along Russia’s Arctic coast to Chinese vessels, significantly reducing shipping times between East Asia and western Europe.

The Biden administration, which published its own “National Strategy for the Arctic Region” in October, said the scientific projects undertaken by China have helped Beijing to increase its influence in the Arctic and “exacerbated” strategic competition in a region where the U.S. has long been a major power.

China Iceland Arctic Research Observatory (CIAO)

Kárhóll, Iceland

Operational date: October 2018

Type of facility / purpose: Newly built research building, farmhouse with accommodation for 10 people, and older farmhouses for service, wet-labs, workshops and storage.

The U.S. strategy document said China has “used these scientific engagements to conduct dual-use research with intelligence or military applications in the Arctic,” requiring the U.S. to respond by positioning itself to “effectively compete and manage tensions” in the region.

China’s state-run Global Times newspaper quickly responded to the U.S. strategy with an article citing Chinese analysts as saying Washington has been “politicizing” China’s activities in the Arctic. It said the Chinese analysts assert the U.S. is “using ‘increased competition’ as an excuse in trying to control the region after seeing its increasingly prominent economic and military value.”

As it snipes publicly at the U.S., Beijing has been less vocal about setbacks to its land-based Arctic scientific projects in recent years and its nascent moves to revive some of them.

Arctic researchers have told VOA that China recently sent several people to the two most important Chinese scientific outposts in Norway and Iceland after lengthy absences of Chinese scientists from both sites. But there have been no signs of China trying to renew two other scientific projects in Sweden and Finland where national organizations told VOA that Chinese activity is set to end or has ended.

Late last year, the Polar Research Institute of China, or PRIC, registered three projects in the scientific community of Ny-Alesund in Norway’s Svalbard archipelago, where it has rented and operated a Norwegian-owned building since 2004 called Yellow River Station, its first Arctic ground facility. PRIC registered the projects on Norway’s Research in Svalbard Portal.

The entrance of China's Yellow River Station research building, rented from a Norwegian company, is seen in this photo taken by Geir Gotaas, Norwegian Polar Institute, in 2015.

Scientist Geir Gotaas, leader of the Ny-Alesund Program at the Norwegian Polar Institute, said Chinese personnel had been mostly absent from Yellow River Station after the start of the pandemic because of travel restrictions—with a Chinese researcher departing in March 2022 after a solo three-month stay at the building, which has a capacity of approximately 10 staff.

But Gotaas said four Chinese scientists traveled to Svalbard in December, with three of them staying for a few weeks in Longyearbyen and Ny-Alesund before departing, while the fourth was scheduled to remain at Yellow River Station until March to maintain instruments during the winter. He said another three Chinese researchers were planning to make a short visit to Ny-Alesund in the first half of February.

“This is another example of Chinese scientists returning to normal operations in Ny-Alesund,” Gotaas said.

A photo of polar lights in the sky above China's Yellow River Station research building in Ny-Alesund, Norway, as published by Chinese state news agency Xinhua. The image is dated March 10, 2008, but VOA could not verify its authenticity.

In northern Iceland’s Karholl, six Chinese personnel, including four scientists, arrived at the China Iceland Arctic Research Observatory (CIAO) in late November after a three-year Chinese absence from the complex, according to its spokesperson, Halldor Johannsson, director of the Arctic Portal.org news organization.

Johannsson said pandemic travel restrictions had kept the Chinese personnel away from CIAO, which opened in 2018 and is jointly operated by China’s PRIC and the Icelandic Center for Research (Rannis). The returning Chinese contingent had a “good visit” with local scientists and community leaders and departed in early December, he added.

CIAO consists of a new research building and several farmhouses for accommodation and other uses. China fully funded the building’s construction but does not own anything at the site and rents the property from Icelandic nonprofit group Aurora Observatory, Johannsson said.

A photo of an antenna dedicated for use by China at Sweden's Esrange Space Center, as published by China's Institute of Remote Sensing and Digital Earth (RADI). The image appeared online in 2018, but VOA could not verify its authenticity.

Esrange Space Center

Esrange, Sweden

Operator: Swedish Space Corporation, which says it controls and operates all antennas at Esrange collaboratively with customers according to terms of each contract.

Type of facility / purpose: Antenna dedicated for use by China's RADI only receives data from earth observation satellites.

Two antennas dedicated for use by China's CMA only receive data from meteorological satellites.

Antenna dedicated for use by China's CLTC receives data from and sends data to satellites and space crafts.

In northern Sweden’s Esrange Space Center, contracts enabling three Chinese scientific agencies to use four satellite dish antennas built from 2008 to 2016 will not be renewed, according to Philip Ohlsson, Swedish Space Corporation (SSC) head of communications.

SSC controls all data received from and sent to satellites by the antennas, three of which are SSC-owned while the fourth is Chinese-owned, Ohlsson wrote in a series of emails. He said Chinese personnel have visited Esrange from time to time but never have been stationed there.

“In 2018, SSC took the decision not to enter into any new contracts with Chinese customers, given the limited size of our company in relation to the complexity of the Chinese market,” Ohlsson said.

Ohlsson declined to reveal when the existing contracts will end, “out of respect for our customers and the confidentiality of these contracts,” as he put it. Those Chinese contracts were still in effect at the end of January, he noted.

Auroral activity above antenna field at Finnish Meteorological Institute's Arctic Space Center in Sodankyla, Finland, is seen in this photo taken by Matias Takala on March 16, 2017.

In northern Finland’s Sodankyla Space Campus, a joint research project launched by the Finnish Meteorological Institute (FMI) and Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) in 2018 ended in 2021 when a three-year agreement expired, said Jouni Pulliainen, FMI Space and Earth Observation Center director.

FMI and CAS Joint Research Center for Arctic Space Observation and Data Sharing, 2018-2021

Sodankylä, Finland

Operator: Jointly operated by Finland's FMI and China's CAS

Type of facility / purpose: Research activity involving CAS personnel visiting Sodankylä and FMI personnel visiting China to cooperate in cryosphere research with satellites.

Delivery of data from European Space Agency’s Copernicus Sentinel-1 to CAS researchers.

CAS announced in 2018 that a joint research center for Arctic space observation and data sharing would be “constructed” in Sodankyla. But Pulliainen wrote in an email that there was no new construction at the space campus and the project mainly involved temporary visits by five Chinese researchers to Sodankyla’s existing facilities before the start of the pandemic.

Pulliainen said the outcome of the project was “not as impressive” as the Chinese side had originally expressed through state media.

“Due to changes in the world’s political situation, we were not any more so interested in deepening the cooperation activities, and we were not contacted from CAS about the renewal of the agreement,” he added.

China also never realized its 2017 proposal to build a satellite dish antenna ground station for remote sensing in the Greenlandic capital of Nuuk.

Beijing Normal University Dean Cheng Xiao held a “launch” ceremony in the Greenlandic town of Kangerlussuaq for the proposed Nuuk ground station on May 30, 2017. A group of more than 100 Chinese visitors attended the event along with two representatives of Greenlandic NGOs, but the project never won approval from the Greenlandic and Danish governments, and it did not proceed.

Proposed Chinese Satellite Receiving Ground Station in Greenland

Nuuk, Greenland

Type of facility / purpose: Proposed construction of a remote sensing satellite ground station antenna in Nuuk to serve people of Greenland, improve climate change research and serve China’s Arctic policy goals.

Note: Greenlandic and Danish governments never approved the proposal and it did not move forward.

China’s foreign ministry did not respond to a VOA email asking why Beijing did not send personnel to the Norwegian and Icelandic project sites for lengthy periods, why it did not reach agreements to extend the Swedish and Finnish projects and why the Greenlandic project never got off the ground.

Marc Lanteigne, a social studies professor at the Arctic University of Norway, said China ran into local opposition for some of its projects.

“I’m thinking primarily of China’s plan to set up a research base in Greenland that was announced to great fanfare and then ran smack into Danish opposition,” Lanteigne said. Denmark, a NATO member, has been “very touchy about anything that might look like a Chinese strategic beachhead” in Greenland, he added.

Lanteigne said China’s diplomatic disputes with some European Arctic nations have undermined the progress of its other scientific projects.

“China’s relations with Sweden really have begun to sour over the past few years due to human rights issues, and that has affected the ability of Chinese researchers to set up any kind of a base in Sweden itself,” he said.

The scientific community of Ny-Alesund in Norway's Svalbard archipelago is seen in this photo taken by Royal Holloway University of London Professor Klaus Dodds in 2018.

Nengye Liu, a law professor at Singapore Management University, said he expects Beijing to focus on developing its more established Arctic projects in Norway and Iceland rather than on smaller projects that ran into obstacles in other nations.

As Arctic ice melts because of climate change, China sees new opportunities for shipping, fisheries and oil and gas development in the region, Liu said.

“So, all these scientific activities are meant to ensure that a major economic power like China won’t be left behind. That is why China describes itself as a ‘near-Arctic’ state,” Liu said.

VOA emailed the White House to request a National Security Council comment on what the U.S. is doing to manage tensions arising from China’s scientific projects in the Arctic but did not receive a response.

In an October forum at Washington’s Wilson Center, Devon Brennan, NSC director for maritime and Arctic security, said the U.S. is concerned that China’s exploitation of Arctic resources, such as fisheries and hydrocarbons, may diverge from what he called the rules-based international order.

But Brennan also said the U.S. recognizes that China has a “vested interest” in the region.

“While first and foremost, we will want to work with our like-minded partners and allies in the Arctic, there is room to cooperate with other non-Arctic nations for the betterment of the region,” he said.