Highlights in China's Development Spending

China’s influence continues to grow through global development and its Belt and Road Initiative. So what’s next?

(Illustration by Walid Haddad / VOA News)

China’s vast overseas development spending has made Beijing one of the most sought-after financiers from countries around the globe.

From 2000 to 2017, China’s loans and grants totaled $843 billion across 165 countries, according to a database by AidData, a university research lab at William & Mary in Virginia.

The massive expenditure is part of China’s vision to invest in primarily low- and middle- income countries, a plan that was ramped up with the creation of its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013. That program initially focused on infrastructure projects — including developing a new Maritime Silk Road connecting China to Southeast Asia, Africa, and Europe — but quickly expanded to include such sectors as health, technology and education. The initiative now stretches to most corners of the world, including Latin America and the Caribbean.

The scale of the Chinese lending has made it the largest state-driven capital outflow since U.S. loans to war-ravaged Europe following World War II, according to the Harvard Business Review, and also surpasses official international lenders, including the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund.

China seeks to make both political and economic gains from its development spending, including strengthening bilateral ties, acquiring access to resources around the world, and making partner countries more interdependent with China’s economy.

“The BRI may be China’s idea, but its opportunities and outcomes are going to benefit the world,” Chinese President Xi Jinping said at the 2018 Boao Forum for Asia in the Chinese city of Boao.

Countering criticism that the initiative is being used as a vehicle for China to further its global influence, Xi said at the forum, “China has no geopolitical motives.”

Critics of the BRI point not only to questions about Beijing’s motives, but also to the high amounts of debt racked up by some poor countries in the program, the willingness of China to invest in corruption-plagued governments, and concerns over the environmental and labor practices at some Chinese development sites.

A global initiative

Source: AidData, “Banking on the Belt and Road,” September 2021

By 2021, 143 countries had formally joined the BRI, accounting for over half the world’s population, excluding China, according to AidData. The regions with the most countries participating in the initiative are sub-Saharan Africa (94%), the Middle East and North Africa (85%), South Asia (75%), and East Asia and the Pacific (73%).

Ammar Malik, a senior research scientist at AidData, describes the scope of the Belt and Road.

“The best way to understand the Belt and Road Initiative, in my view, is to consider it as a bit of a cloud under which — or an umbrella under which — a lot of activity is taking place,” says Malik. “Belt and Road is not a single entity. It is not a budget line in the Chinese government’s budget. It is a concept. It is an umbrella under which many entities are delivering projects in many countries across many sectors around the world.”

China’s overseas development spending significantly jumped with the introduction of the BRI in 2013, but its spending also spiked before that — in 2009 following the global financial crisis at the end of 2008. Beijing responded to the crisis by unveiling a massive stimulus package, which led to state-owned companies building roads, railways and airports across China, but which also led to overproduction. This in turn led to Chinese companies becoming unprofitable, and fears by the government that the situation could lead to unrest. To address the problem, China redirected state-owned companies to overseas development projects.

Boston University associate professor Min Ye said during this time of overcapacity, some Chinese factories were overproducing by as much as 30%.

“After 2008, China’s stimulus was, like, trillions of dollars,” say Ye. “It was so massive. And they threw the money into the domestic producers in just 18 months. And so, they built so much. And then they couldn’t have a domestic market. If they keep doing it, they could keep stimulating, but then the environment would not have been able to tolerate [it].”

Market rates

While China offers concessional loans with rates lower than a commercial bank, much of Beijing’s international financing is priced near or at market rates, due to China’s willingness to invest in higher-risk places and sectors such as mining, according to Malik. In contrast, the World Bank Group and many Western nations mainly offer loans to low- and middle-income countries at below-market rates.

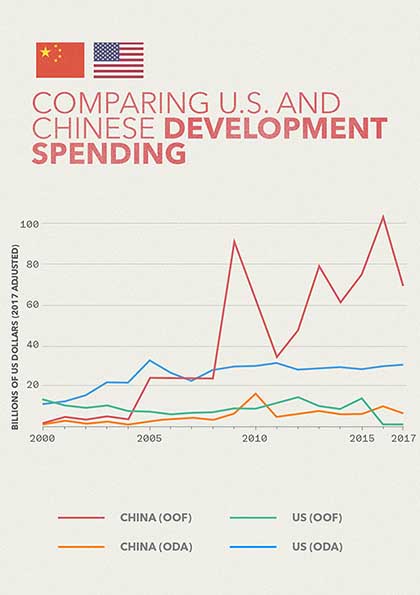

Since China introduced the BRI, it has maintained a 9-to-1 ratio of Official Development Assistance (ODA) to Other Official Flows (OOF), according to AidData. Financing that qualifies as ODA, as defined by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, contains a grant element of at least 25% and includes loans that are mostly below-market rates, while OOF financing contains a lower grant element, along with less-forgiving loans.

Source: AidData Global Chinese Development Finance Dataset, Version 2.0

In addition to offering mostly market rates for its loans, many of China’s loans are backed by collateral, meaning the debt repayments are often secured by the sale of exports back to China, including oil, gas and minerals. China uses this collateral system to mitigate against the risk of investing in less stable countries, with AidData calling the practice “the linchpin of China’s implementation of a high-risk, high-reward credit allocation strategy.”

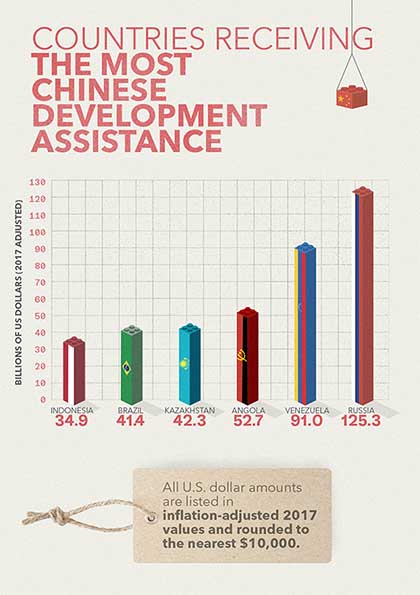

Source: AidData Global Chinese Development Finance Dataset, Version 2.0

The top three recipients of China’s overseas development spending — Russia, Venezuela, and Angola — are all countries that receive a large share of loans that are collateralized with the proceeds of oil sales to China.

U.S.-China comparisons

At the turn of the century, the United States was slightly outspending China in its overseas development, but by 2017, China was outspending the United States and other major powers on a scale of 2-to-1 or more, according to AidData.

Source: AidData, “Banking on the Belt and Road,” September 2021

U.S. President Joe Biden announced in 2021 that the United States would work with other G-7 countries to create a global infrastructure initiative meant as an alternative to China’s program. The Build Back Better World initiative aims to help emerging economies meet infrastructure needs while also prioritizing the fight against climate change. However, it is still unclear whether the new initiative can emerge as a viable alternative to China’s far-reaching overseas spending program.

Biden administration officials have largely sought to downplay any competition between the United States and China related to overseas development spending. When asked about the U.S. response to China’s footprint in Africa, U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Linda Thomas-Greenfield told VOA in February, “We’re not asking African countries to choose between their friends and choose who they will partner with.”

When lending to emerging economies, the United States, along with other Western powers, favor ODA loans, or those with a higher percentage of grants and favorable loan rates, while China puts the majority of its financing in OOF, or financing with a lower aid component along with loans that are closer to market rates.

Malik at AidData describes how China’s loans differ from those of Western donors.

According to Malik, “When we do a comparison of China’s overseas loan-giving program and compare it to typical Western donors, we found that Chinese loans tend to be more expensive. On average, a Chinese loan is [a] 4.2% interest rate, according to our dataset, with a repayment period of 10 years. Whereas Japan or Germany would give the same sort of loan for around 1% with a much longer repayment period of 28 years.”

Spotlight: Africa

While much of China’s lending is made up of concessional loans that tend to be near market rates, loans to Africa are an exception. Malik said that unlike other regions of the world, 78% of Chinese overseas development financing in Africa is in the form of aid.

“The most distinctive feature of China’s engagement in Africa, in my view, have been the large share of aid projects that they’ve given out,” says Malik. “In many cases, we have seen Chinese health teams repeatedly for a number of years going back to the same town or the same village, sometimes on a ship, sometimes on foot, and setting up camp every year consistently for 16 or 20 or 25 years sometimes, in order to provide health care services.

Megaprojects

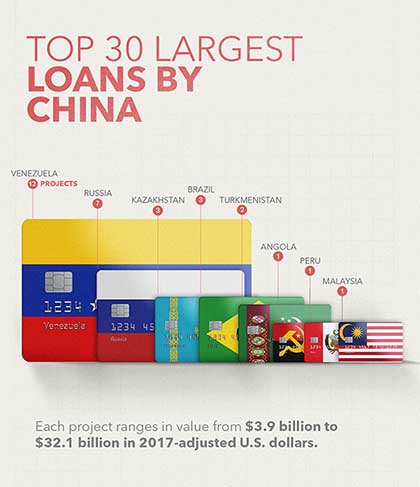

Since China began the BRI, the financing of megaprojects — involving loans of $500 million or more — significantly increased, according to AidData. Their data show that in the years before the initiative was introduced [2000-2012], China approved 11 loans per year for megaprojects, while in the years following Belt and Road implementation [2013-2017], that number jumped to 36 loans in an average year. The 30 largest projects that China is financing are in just eight countries.

Source: AidData, “Banking on the Belt and Road,” September 2021

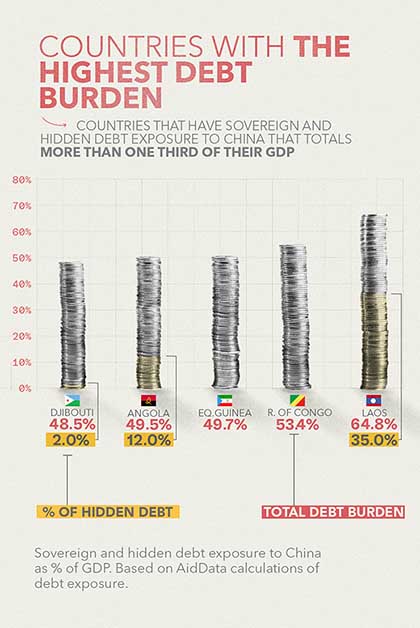

Debt burden

The increase in China’s overseas lending has led to 42 low- and middle-income countries having levels of debt exposure to China in excess of 10% of their GDP, according to AidData. Their research also shows that debt to China is often significantly under-reported to the World Bank, because in many cases, the loans are set up in new ways which do not appear on the balance sheets of host countries. The result is that some countries have significant sums of hidden debt, in addition to growing sovereign debt.

Source: AidData, “Banking on the Belt and Road,” September 2021

Because of the debt crisis in some countries, Malik said China has increased the amount of short-term loans it is giving out. He added the loans give countries an injection of cash to help them stay afloat and to eventually repay the loans that they had taken in the previous era. But because global interest rates are on the rise, the new short-term loans tend to be at higher interest rates.

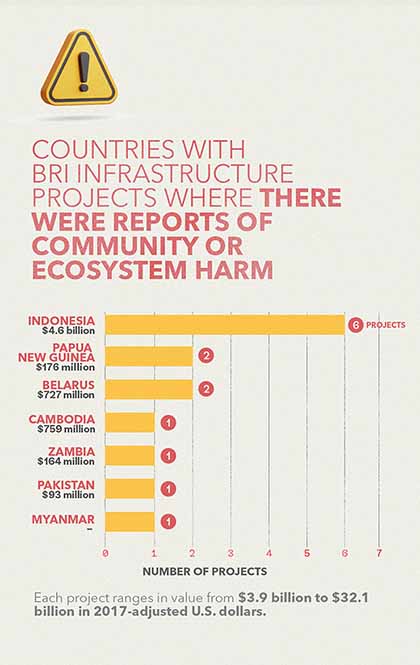

Implementations challenges

AidData found that 35% of BRI infrastructure projects encountered major problems during their implementation, including corruption scandals, labor violations, environmental hazards and public protests. AidData based its findings on reports of such issues but did not independently evaluate the claims. Regarding problems labeled as community or ecosystem harm, the data found such issues disproportionally occurred in three countries: Indonesia, Papua New Guinea and Belarus.

Source: AidData, “Banking on the Belt and Road,” September 2021

Looking ahead

In recent years, China has been moving away from a heavy focus on infrastructure projects in its overseas financing, toward the sectors of health, digital development and green energy, according to Ye of Boston University. She said the path forward for the West and China will depend on whether or not the West can accept a non-democratic superpower in China.

According to Ye, “So, what China pursues, in my opinion, is to really make its own political system more legitimate internationally, to make its own system more acceptable internationally, as a legitimate international system.”

While China’s overseas development spending has resumed after a pause during the global coronavirus pandemic, Malik predicts the next dataset from AidData will show that Beijing’s spending is slowing. He said this is because interest rates have gone up across the world, making loans more costly, as well as the fact that many low- and middle-income countries are already heavily indebted.

He said whether countries that receive Chinese loans can prosper from the investments will depend not just on the initial foreign financing, but also on whether governments can put in place reforms to sustain long-term changes.

According to Malik, “Whether a developing country is able to convert that initial investment into foreign direct investment, create jobs for their economy and become more competitive in the international market depends on not just the scale of Chinese investments but also the governance structures that are put in place in these developing countries. And that is, in my view, the biggest challenge right now.”