‘I forgot about my own fear’

The director of Afghanistan's leading TV channel knew that staying on air could help restore calm.

When the Taliban took over, keeping (news outlet) TOLO on air and securing our compound became a matter of honor.

Most of our staff left in panic, and I realized that if we went off air, it would have a negative impact on the public.

I also knew it would be a difficult, if not impossible, task to get us back on air.

Throughout the day (August 15), my wife, my son and my daughters kept calling, asking me to come home.

All I could tell them was that I was alive and well but couldn’t leave. I was so single-mindedly focused on my mission that I forgot about my own fear.

With the help of a skeleton staff, we kept TOLO on air. And to reassure the public, we repeatedly aired a Ministry of Interior statement that mentioned a peaceful transfer of power.

I had no idea at the time that the minister who issued that statement had already left the country, as had the president.

I later contacted Taliban spokesperson Zabihullah Mujahid, and he too reassured me that the Taliban had no plans to enter the city.

But by the evening, it was all over. There was no government to speak of, and we were getting reports of (looting) from across the city.

To reassure the public, I called Mujahid again and invited him on our show. He gave us a 15-minute phone interview that we carried on all our TV and radio channels.

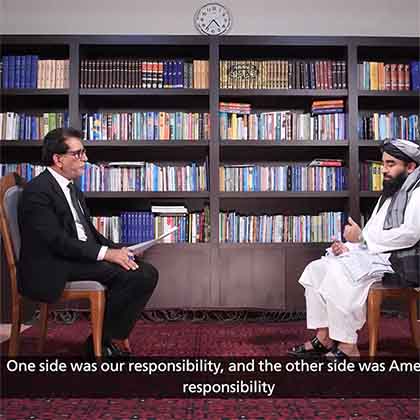

Khpalwak Sapai interviews Taliban spokesman Zabihullah Mujahid in October, 2021. (Screenshot: TOLOnews)

In the days that followed, staff shortages were a major problem.

The morning after the fall of Kabul, we started with a rebroadcast because we didn’t have an anchor.

But as staff saw that we were on air, some, including female presenters, started showing up, and our broadcast schedule gradually returned to normal.

When a Taliban official called and asked if he could come on to discuss the situation, I agreed.

When he arrived, the news anchor (Beheshta Arghand) was on the set, so we seated him next to her. Their interview made a splash around the world.

Arghand later fled Afghanistan, citing safety fears.

More than 90% of our staff quit and never came back. Among them were our most experienced reporters, well-known anchors, editors, camera operators. All of them rushed to the airport.

The staffing situation was so bad that on no fewer than three occasions we came close to going off air.

We had to replace everyone. But finding new talent is hard when journalists from across the country – the best and the brightest – scramble to leave.

I contacted former employees and asked them to come back. I hired new reporters. They lack experience, but they are motivated and work hard.

The quality of our programming took a hit, but this was to be expected.

Naturally, there are (other) problems. Access to information is far more restricted under the Taliban. We have a different government in place. The work environment has changed. They’ve given us new media guidelines, and we have no choice but to follow them.

But that doesn’t mean we act like the state broadcaster and air whatever the Taliban say.

Some of our presenters ask tough questions. Our on-air discussions are independent. Our analysis is independent. Our news reporting is independent.

There is no certainty what tomorrow brings and whether independent journalists will still be able to work. The Taliban’s new media law will clarify just how far we can go. I may not like their guidelines and decide to quit. It’s too early to say.

We’ve lost too many people, and the exodus continues.

The doors, the ceilings, the hallways, the rooms and the studio are all the same at TOLO, but our people are gone. I can’t forget them.

Whenever I walk around the station and see an empty chair and the area where our staff used to drink tea and smoke cigarettes and joke around, or I walk into a studio, memories flood back.

In the past three to four months, my optimism has dampened.

Restrictions and pressure are increasing by day, as are threats, making it more difficult for journalists and the independent media to operate. If the situation doesn’t change materially, I’m not certain how much longer the independent media can survive.

There are a lot more restrictions in the provinces. (Those) journalists are asked to clear stories with local authorities. That is overt censorship.

The Taliban detained Sapai and two other TOLO employees briefly in March after the station reported on Taliban directives to not air foreign dramas.

My impression is that the Taliban are internally divided over the very existence of an independent media. Some recognize the need, but more of them don’t.

Often, they have the same expectations of the independent media as they do of government-controlled media.

The change in my view has absolutely nothing to do with my recent detention. It’s a general view. It’s not about one person or one outlet. It’s about the entire media landscape.

Earlier, I didn’t think much about leaving Afghanistan. I was more focused on keeping a major outlet alive, and I viewed that as a personal achievement.

At the moment, whatever drive I had to stay in Afghanistan has been lost.

Interviews with Sapai have been translated and edited for length and clarity. TOLONews is a VOA affiliate.

About this project

Hundreds of Afghan journalists fled after the Taliban takeover last year, but many more chose to stay in spite of the regime’s hostility. Masood Farivar, former chief of VOA’s Afghan Service, interviewed several about what drove them to their decisions, and how their work has changed in a culture of intolerance.

— Jessica Jerreat, VOA Press Freedom Editor