The Imam’s Choice

How a Milwaukee cleric’s advice changed the course of an FBI sting.

Photos by Marco Monge for VOA

How a Milwaukee cleric’s advice changed the course of an FBI sting.

By Masood Farivar | Illustrations by Brian Williamson | VOA News

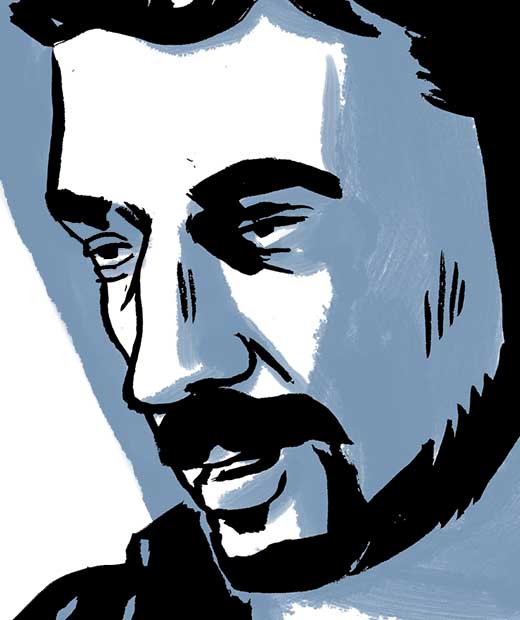

Samara was in the final year of a Ph.D. program at the University of Wisconsin at Milwaukee and led a congregation of Muslims at a mosque near campus.

The call came from an unidentified number. Against habit, Samara decided to take it.

Imam, I'm in the mosque downstairs. I need to talk to you about something important and urgent.*

Samara sensed impatience in the stranger’s voice. Fearing that an outsider might have broken into the mosque, Samara demanded to know who the caller was.

“My name is Samy Hamzeh,” the man told him.

Kamil SamaraSamara, a 40-year-old native of Jordan, lived in the house next door with his wife and their two children. When he got to the mosque, he found a man about half his age, dressed in jeans and a black jacket.

Kamil SamaraSamara, a 40-year-old native of Jordan, lived in the house next door with his wife and their two children. When he got to the mosque, he found a man about half his age, dressed in jeans and a black jacket.

At the time, Samara led more than 300 worshippers each Friday in prayers. Most were University of Wisconsin students and faculty members. He didn’t recognize Hamzeh.

The men shook hands and sat. Hamzeh got right to the point.

Can I entrust you with a secret?

Can I entrust you with a secret?

“I said ‘Of course!’ ”

The imam had no way of knowing it, but Hamzeh had become the target of an FBI terrorism sting. The choice he’d just made – to hear Hamzeh out – would alter the course of that investigation and provide a vivid example of how Muslim leaders can be a moderating force against extremist ideology.

In interviews with VOA, Samara told his behind-the-scenes story of the case for the first time. Along with details from court records, including surveillance excerpts, his account provides a rare look at the inner workings of an FBI sting.

As their conversation continued, Samara said Hamzeh launched into a rage-filled tirade.

“Muslims are being oppressed everywhere, being killed everywhere – in Burma, Palestine, Africa,” Hamzeh vented to the imam. He then aimed his fury at the Masons, an association of fraternal groups that has become a favorite subject of conspiracy theorists.

Hamzeh asserted that the Masons controlled the U.S. government.

“It was anger that was driving him,” Samara told VOA. “It wasn’t like some other people who are taking verses from the Quran or hadith and twist them and they convince themselves that this is the truth. He didn’t go that far. He was not there.”

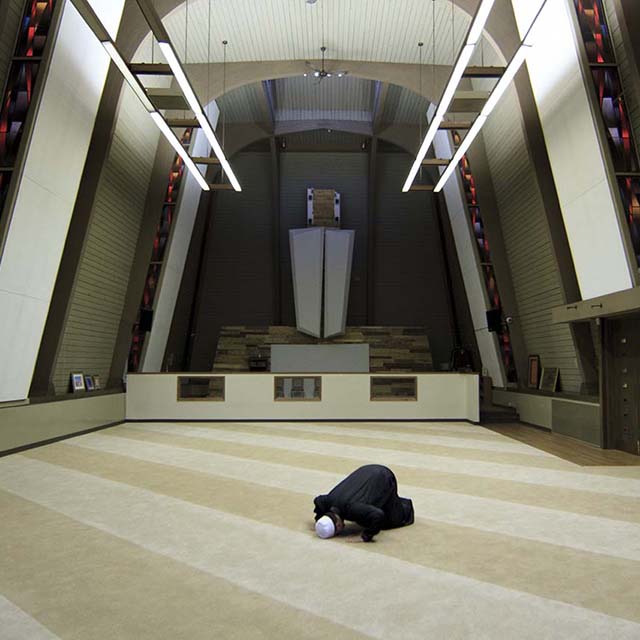

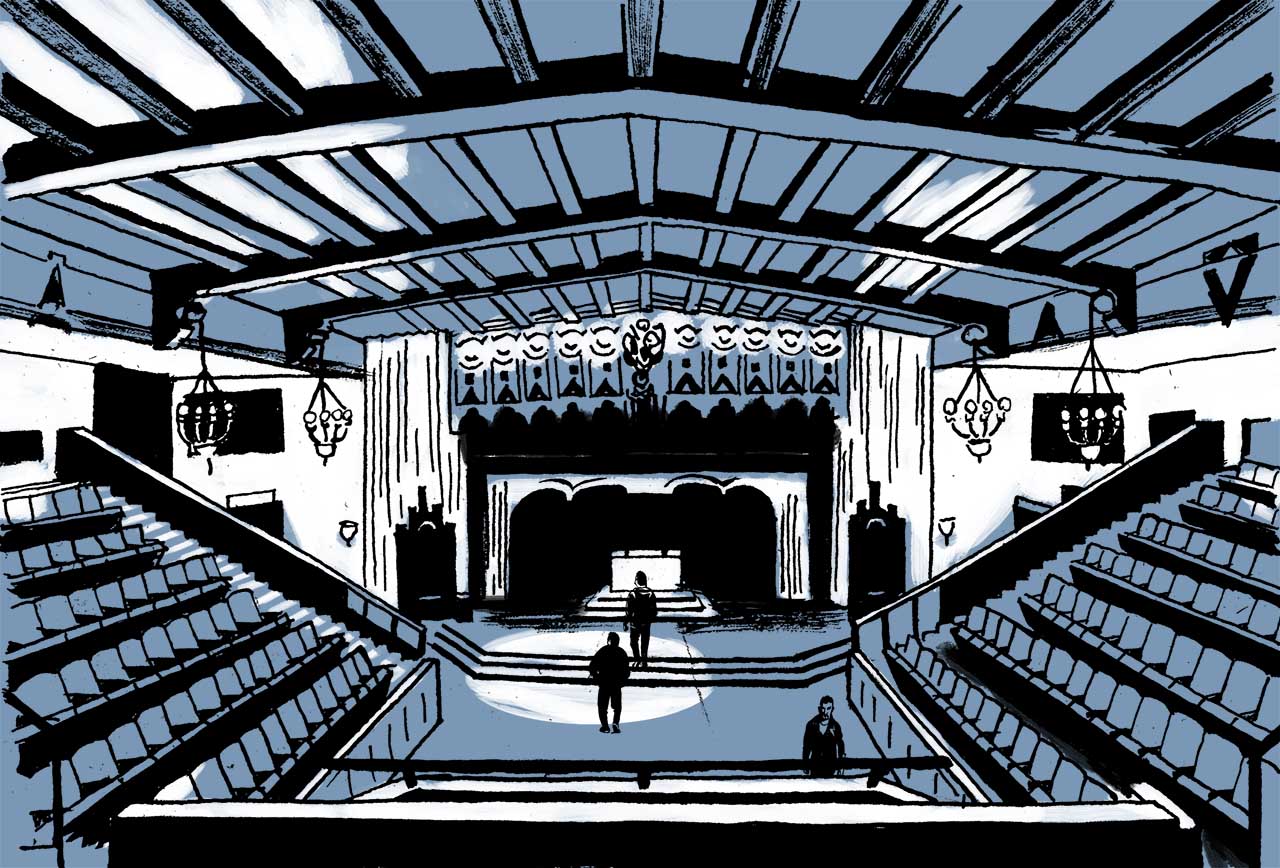

The Masons, Hamzeh told Samara, had a temple in downtown Milwaukee. Samara hadn’t heard of the temple, called the Humphrey Scottish Rite Masonic Center, though he was familiar with discredited claims that Masons had created the extremist group Islamic State to destroy Islam and kill Muslims.

Then the conversation took a fateful turn.

Me and another two guys, my friends, we're planning to acquire guns, go there and shoot the people in the temple.

Then the conversation took a fateful turn.

Me and another two guys, my friends, we're planning to acquire guns, go there and shoot the people in the temple.

Shock and fear jolted Samara.

Shock and fear jolted Samara.

Before him sat a man contemplating a deadly rampage.

Before him sat a man contemplating a deadly rampage.

His mind raced. “What am I getting myself into? Why did I answer that call?”

Hamzeh then asked Samara a direct question.

“Is this right, what I’m trying to do?”

“No,” Samara replied. “It is haram” – forbidden by Islam.

Still reeling, Samara searched for the best arguments he could muster to change his interlocutor’s mind.

“First of all,” Samara began, “when we came to this country, we came with a covenant that we live in peace, follow the laws and respect the institutions of this country.”

Hamzeh did not interject.

“Number two,” Samara continued, “you’re killing innocent people, and this is against the teachings of Islam. We’re not sure these people are having any relations with all the massacres and bad things happening to Muslims.”

“And third, what would happen to you after that?” Samara asked. ”You’ll be shot and killed or thrown in prison … Is this what you want?”

Hamzeh listened silently. “He didn’t argue much,” said Samara.

The exchange lasted 20 minutes.

As he got up to leave, Hamzeh showed no sign that he’d been swayed. Before the imam saw him off, Samara offered to set up a meeting with the mosque’s more senior leaders. But Hamzeh wasn’t interested.

After the visitor left, Samara panicked. Was Hamzeh on the verge of a massacre? Or just a confused young man?

“I was not sure what to do,” he said.

Samara immediately alerted the leadership of the Islamic Society of Milwaukee, the organization that oversees Samara’s mosque.

He phoned Ziad Hamdan, the imam at the society’s main branch in downtown Milwaukee. Hamdan, in turn, contacted the mosque’s two senior leaders.

“We obviously took it extremely seriously,” recalled Othman Atta, then the society’s CEO. “We wanted to make sure that we’d be able to respond to that if somebody was really thinking about it.”

After a flurry of frenetic phone calls, text messages and emails in the next two hours, the leaders decided to arrange a meeting with Hamzeh the next day and then alert the FBI.

They never got to do either.

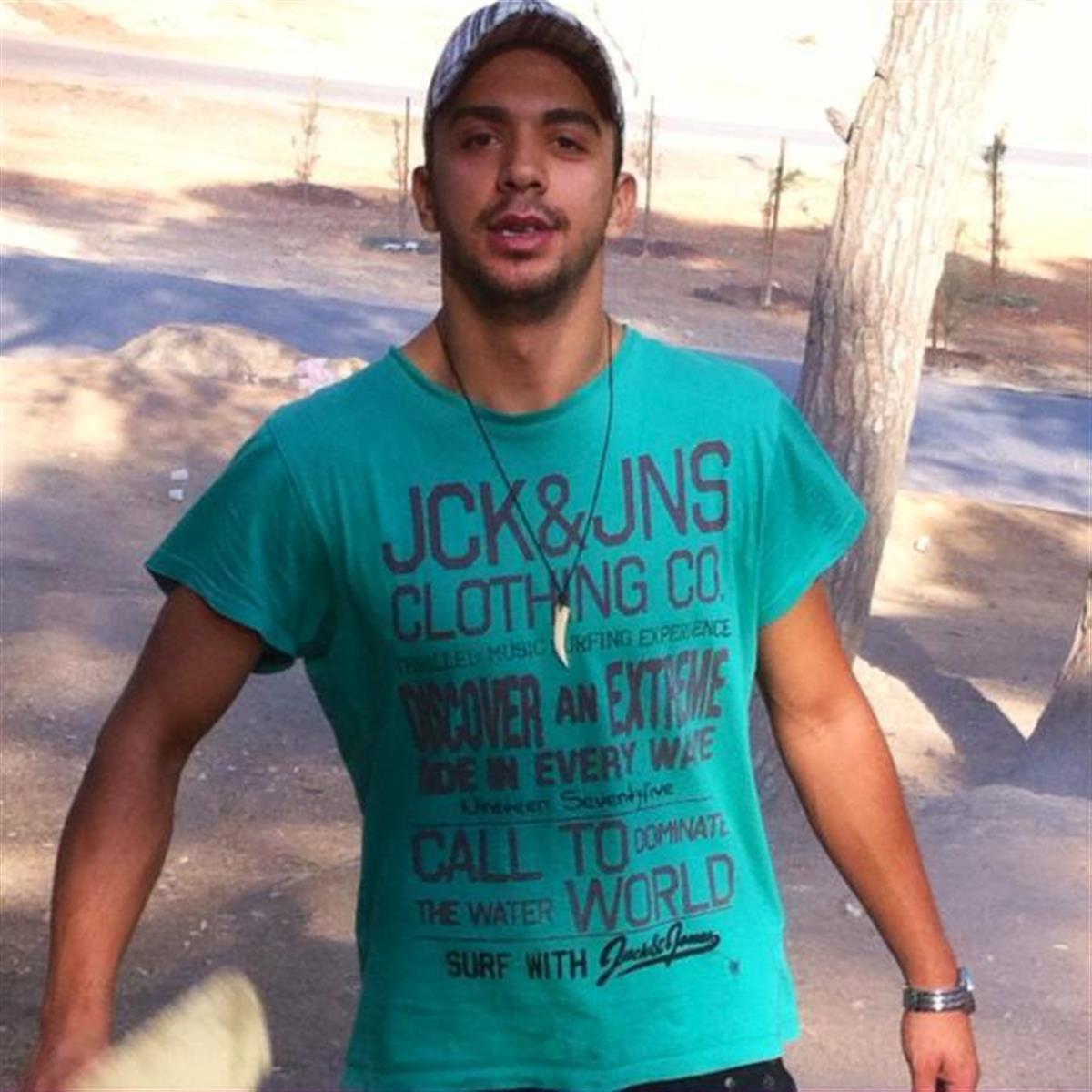

Samy Hamzeh, now 25, is the son of Palestinian immigrants. He was born in New Jersey, but when Hamzeh was three, the family moved to Jordan, his parents’ home. In 2011, the 19-year-old Hamzeh returned to the United States. He settled in Milwaukee, a city with a small Palestinian community that traces its roots to the 1960s.

Hamzeh was joined by his parents and younger sister two years later. They lived together in an apartment, and the burden of supporting the family fell on Hamzeh.

He took odd jobs, working as a delivery driver, bus boy, gym trainer and valet while taking classes at a community college. He had no criminal record and wasn’t fervently religious. Defense documents say he used hashish. Hamzeh handed his paychecks over to his father, the filings say, taking only a small allowance in return.

Hamzeh appeared on the FBI’s radar on Sept. 16, 2015, when a friend reported him to the agency’s Milwaukee office.

Court documents say the friend told agents Hamzeh “was talking about traveling to Egypt for terrorist training, obtaining a commercial driver’s license to conduct a terrorist attack in the name of ISIS [Islamic State], and that he’d obtained a .45 caliber pistol.”

The Islamic State was on the retreat in Iraq and Syria, but concern remained high in the United States about the risk of Muslim Americans joining the terrorist group. Believing they had a would-be jihadist in their sights, agents opened an investigation. They asked Hamzeh’s friend to start recording his conversations with him.

The friend, identified as “Steve” in court filings, reported within a week that Hamzeh had “changed his mind about doing stupid things.” Still, the FBI brought in a more experienced informant a few days later: “Mike.”

Both Mike and Steve are of Palestinian descent, according to several members of the Milwaukee Muslim community. Defense records indicate Steve did not have work authorization papers. It’s unclear whether the two were paid, but the FBI routinely compensates informants. The agency keeps a roster of 15,000 paid and unpaid informants, according to a budget request to Congress.

Defense filings depict Mike as the more aggressive of the pair. Planted in the same restaurant where Hamzeh waited tables, he befriended Hamzeh and tried to “steer the conversation toward extremism and guns,” defense filings assert.

Within days, he introduced Hamzeh to guns, showing him and Steve his pistol and suggesting they all go to a shooting range.

As an informant’s quarry, Hamzeh did not disappoint.

In conversations reported or recorded that October, November and December, Hamzeh told Steve and Mike things that even his defense team termed “unsettling.”

He talked about traveling to Palestine to “buy a weapon and shoot civilians or military personnel.” He vowed to join the terrorist group Hamas and “strap on a suicide vest to prove his loyalty.” He planned a martyrdom mission to Israel where he would “get a machine gun and fire it randomly” at soldiers and civilians.

At least three times, Hamzeh told Steve and Mike that he wanted to buy a gun.

According to his lawyers, all this was little more than bluster. Hamzeh “was just making up stories to impress or entertain his friends,” they wrote in a filing seeking bail.

To prosecutors, however, it showed Hamzeh was serious about a mass terrorist attack.

By January of 2016, the investigation hadn’t produced a chargeable offense. But in the middle of that month, things took a turn.

Mike informed the FBI that Hamzeh had begun “talking about an attack on the Masonic center in Milwaukee,” defense filings state. Hamzeh, Steve and an unidentified person had watched videos about the Masons on cell phones, Mike reported.

Among other things, the incendiary videos linked the Masons and Islamic State and claimed members of the group “talked to the devil,” “kidnapped [and] grabbed some people” and “cut them to pieces.”

Hamzeh’s lawyers say it was Mike who exposed Hamzeh to the videos, cooked up the plot and induced Hamzeh to take part. But prosecutors argue that Hamzeh “carefully planned the shooting and recruited people to join the attack.”

They paint Hamzeh as the mastermind. In blood-curdling detail, they say, Hamzeh told Steve and Mike how many machine guns and silencers they’d need to execute everyone at the temple and make a daring escape.

On Jan. 19, prosecutors say, Hamzeh went to the local shooting range with Mike and Steve to practice using a handgun.

Later that day, the trio took a guided tour of the Masonic center.

They learned of the temple’s layout and determined how many people attended weekly meetings there: 30.

They talked into the early morning hours about machine guns and an attack. Hamzeh was recorded saying:

Thirty is excellent. If I got out after killing 30 people, I'll be happy 100 percent.

They talked into the early morning hours about machine guns and an attack. Hamzeh was recorded saying:

Thirty is excellent. If I got out after killing 30 people, I'll be happy 100 percent.

But after meeting with Samara five days later, Hamzeh had a change of heart.

That night, he visited Steve to say he was quitting the plot. Citing the imam’s advice, he urged his friends to do the same lest they all go to hell.

“I told you this operation will be considered haram,” Hamzeh is quoted saying in surveillance excerpts. “He, the Sheikh, told me this plan will be forbidden because people will not trust and they will kill and slaughter Muslims and all this will be because of what you did and it will be your fault.”

As Steve and Mike pushed back, Hamzeh grew flustered and implored them to “listen to someone who understands religion.”

“What do you want me to do?” Hamzeh barked. “God damn your religion, go talk to the Sheikh.”

But the informants were unfazed.

Samara, Mike told him, was not to be trusted because he’d only recently become a Muslim (Samara, raised as an Orthodox Christian, had converted in 2002). But Hamzeh defended the imam, saying Samara told him “what he needed to know.”

To get a second opinion, Hamzeh called an uncle in Jordan who is also an imam. The uncle confirmed Samara’s view: The planned operation would be haram.

The temple plot had come apart thanks to Samara’s 11th-hour admonition.

But Hamzeh had not given up on a long-running interest in guns, and Steve and Mike knew it. When Steve said they could “get the weapons” from one of Mike’s contacts the next day, Hamzeh readily agreed.

Just what kind of a gun Hamzeh wanted and for what purpose is in dispute.

His lawyers say Hamzeh wanted a handgun for protection while working as a delivery driver in dangerous neighborhoods. Prosecutors say Hamzeh wanted machine guns for an attack.

Hamzeh agreed to meet two gun sellers Mike had lined up. On Jan. 25, the day after seeing Samara, Hamzeh and Steve arrived in a hotel room.

The sellers were actually FBI agents working undercover.

The sellers were actually FBI agents working undercover.

The agents showed Hamzeh a rifle.

But Hamzeh said he wanted a smaller gun.

They produced two MP-5 machine guns, one of which was outfitted with a silencer.

The agents wanted $1,000 for both weapons (a Heckler & Koch MP-5 has a price of $2,500 or more). That was more money than Hamzeh and Steve had, so the agents cut the price to $570 – $270 for Hamzeh’s gun and $300 for Steve’s.

Hamzeh had only $200 on him and had to borrow the rest from Steve to pay.

The undercover officers provided Hamzeh with a green bag to carry the guns to his car. As he placed the bag in the trunk, Hamzeh was interrupted.

He was under arrest.

Hamzeh is being held in Kenosha County Detention Center. (Photo courtesy of Waukesha County Sheriff's Department)

The news broke in a burst of laudatory coverage for law enforcement.

Milwaukee Mayor Tom Barrett said: “My message to the city of Milwaukee is we should be incredibly thankful to the FBI and the U.S. Attorney’s Office for acting so decisively and so quickly to apprehend this individual and to thwart this threat.“

Mug shots of “terror suspect” Hamzeh dominated the reports, and the Islamic Society of Milwaukee said law enforcement had “protected our community.”

Left unmentioned was Samara’s role.

In court filings, defense lawyers say Hamzeh faced a “moral crisis” and sought spiritual counsel “outside the echo chamber Mike and Steve created.”

Prosecutors say that while Samara’s intervention made a difference, it wasn’t the main reason Hamzeh backed out. Instead, they say, Hamzeh was afraid word of the plot had been leaked and he would be caught.

They have used Hamzeh’s quest for religious guidance against him.

“That the defendant needed two imams to tell him mass murder is wrong shows he is dangerous,” U.S. Attorney Greg Haanstad argued at a bail hearing in July.

Hamzeh faces three counts of receiving an unregistered weapon, with each carrying a maximum sentence of 10 years in prison. He is being held in Kenosha County Detention Center south of Milwaukee.

The FBI says undercover operations such as this have deterred attacks and saved lives. But civil liberties groups say some stings amount to entrapment – luring suspects to commit crimes they otherwise would not.

Since 9/11, there have been more than 800 terrorism-related prosecutions, with about a third involving FBI sting operations that relied on informants, according to a database compiled by The Intercept, an online news site.

Hamzeh does not dispute the gun purchase; he was caught red-handed as an FBI camera rolled. Instead his lawyers plan to raise an entrapment defense, claiming the idea to buy expensive machine guns originated with the informant Mike.

“The idea becomes, whose idea was it that this gun that Samy Hamzeh wanted for protection but couldn’t afford became a machine gun?” said Daniel Stiller, who formerly headed the Federal Defender Services of Wisconsin and has closely followed the case.

But to date, no entrapment defense has succeeded in a terrorism-related case. The bar is high. Defendants must first admit they committed a crime, then argue they were not “predisposed” to carry it out.

“So you have this natural bias that a jury is going to feel,” said Andrea Prasow, who as deputy Washington director for Human Rights Watch has extensively studied post-9/11 terrorism investigations. “Someone says, ‘Yes, I dialed that cell phone number thinking a bomb was going to blow up a bunch of innocent people’ … and the jury stops listening.”

Prosecutors and defense lawyers declined to comment to VOA ahead of Hamzeh’s trial, scheduled for Feb. 12, 2018.

Some who’ve followed the case say Samara’s role is pivotal to an entrapment defense.

The fact that Hamzeh sought spiritual guidance “is pretty powerful evidence that the defendant didn’t on his own have it in him to carry out what the informants were proposing,” Stiller said.

For some time, Samara thought his advice had failed. That was based on news reports suggesting Hamzeh had gone ahead with his plot.

But after VOA tracked Samara down and shared details from court documents, he came to believe he made a difference.

“I feel happy I was able to change his mind,” said Samara, who still lives next to the Milwaukee mosque, but now works as an assistant professor of computer science at Illinois Wesleyan University.

“I really believe all the imams in the U.S. (would) provide the same advice.”

Reflecting back, Samara said, Hamzeh was a “confused” young man. “I think if we had enough time to talk to the kid, things would have gone differently,” he said.

Atta, of the local Islamic Society, said Samara “clearly gave (Hamzeh) a message that what you’re doing is haram. He seemed to be convinced by that.”

“My belief is Samy deep down knew it was wrong,” Atta added. “He needed or wanted someone with some credibility to reinforce what he truly believed.”

Hamzeh’s lawyers have contacted Samara about testifying at the trial.

“I’ll tell the truth,” he said. “Hopefully, it’ll help him.”