What is the entrapment defense?

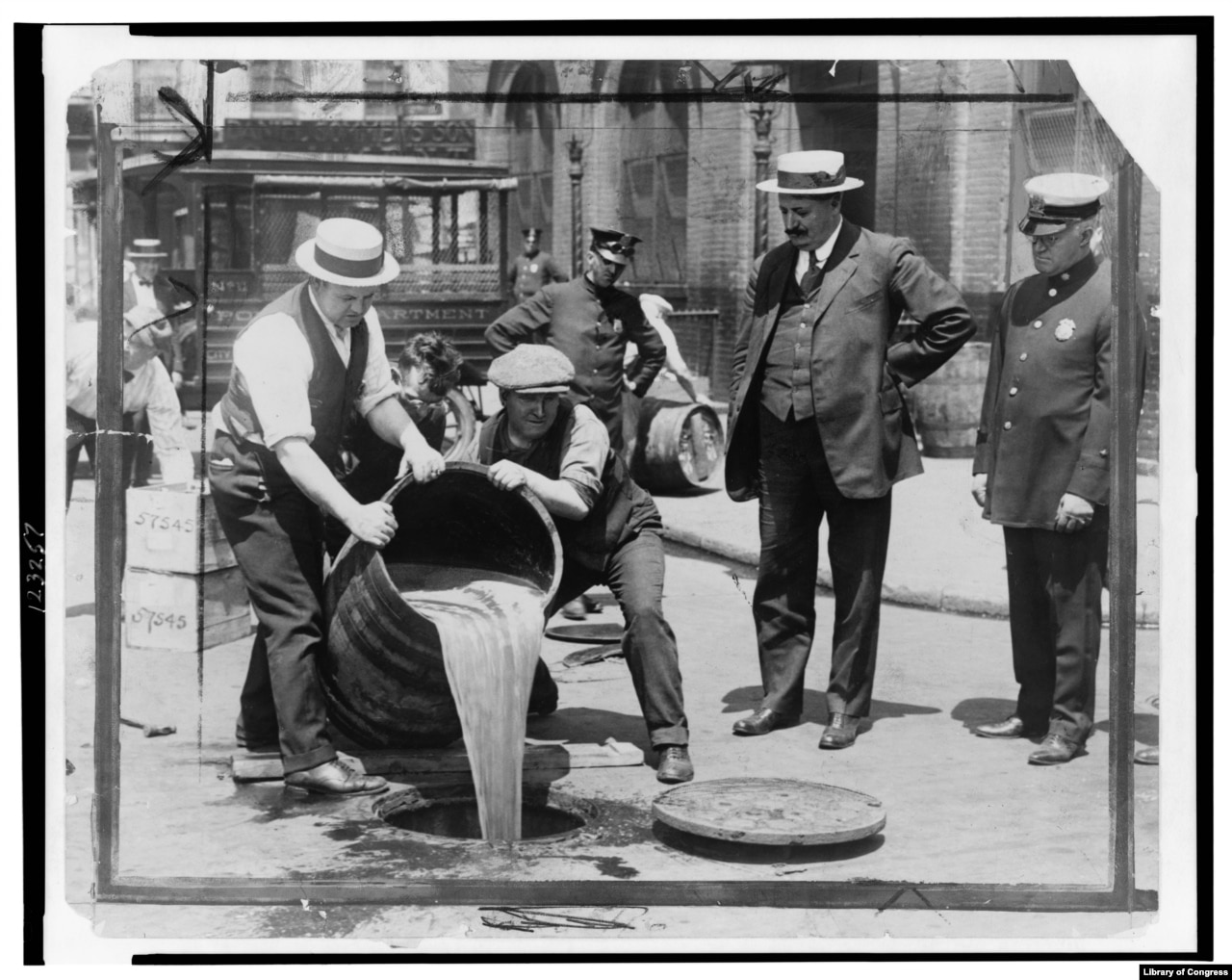

The roots of the defense strategy go back to a Prohibition-era case that eventually went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

By Masood Farivar | VOA News

Thank an alleged Prohibition-era bootlegger named C. V. Sorrells for the entrapment defense.

In 1930, Sorrells, a World War I veteran, was convicted of violating the National Prohibition Act for selling a half gallon of whiskey to an undercover federal agent.

C. V. SorrellsSorrells said he had been entrapped because the agent repeatedly asked him to get whiskey.

C. V. SorrellsSorrells said he had been entrapped because the agent repeatedly asked him to get whiskey.

The lower courts didn’t buy Sorrells’ argument. But the Supreme Court took his case, reversing his conviction on the grounds that the government had “instigated” an “otherwise innocent” person into committing the crime.

The ruling set the legal standard for an entrapment defense. To claim entrapment, a defendant must argue that he or she lacked a “predisposition” to commit the crime and was “induced” into carrying it out.

A 1992 Supreme Court decision (Jacobson v. United States) affirmed entrapment as a defense and a 1994 appeals court ruling (United States v. Hollingsworth) defined predisposition as both the willingness and ability to commit an offense.

The FBI has long used informants to infiltrate the mob, bust child pornography rings, and catch other criminals. But 9/11 made counterterrorism a high priority. “Your job is to prevent an attack, not to investigate after the bomb goes off,” said former FBI agent David Gomez.

FBI agents who work with informants are required to follow strict procedures. Undercover operations must be “conducted with extraordinary care and precision” so that “suspects are neither entrapped nor denied legal protections,” then-Attorney General Eric Holder said in 2014.

But critics say that’s not always the case. An extensive study of post-9/11 terrorism cases by Jesse Norris, an assistant professor of criminal justice at State University of New York, Fredonia, found that “facts and allegations supporting an entrapment defense” were “quite widespread.”

What ever happened to Sorrells?

The Supreme Court sent his case back for retrial. A judge dismissed the charges.