“There was nothing illegal about publishing what we published … The problem with what we did was publishing it in Kurdish.”

—Sajjad Jahan Fard

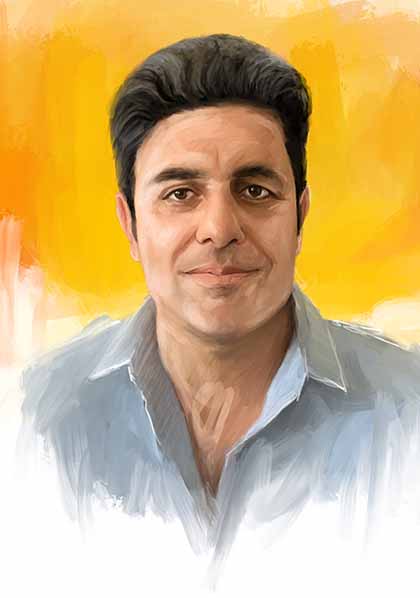

(Portrait by Lukman Ahmad | VOA News)

With a sizable population and rights laid out in the constitution, the Kurdish community in Iran should arguably have a thriving media scene.

But as journalist couple Anise Jafarimehr and Sajjad Jahan Fard found, running a magazine can be treacherous.

Through a combination of Tehran’s repressive laws and expansive censorship, journalists are persecuted for their culture and their profession, forcing many —Jafarimehr and Jahan Fard included — to go into exile.

Part of the problem stems from two vaguely worded articles in the constitution, related to media freedom and regional language.

Both allow for a lot of interpretation, especially when it comes to Kurdish-language media, experts say. And both allow for curbs, especially for content deemed “detrimental to the fundamental principles of Islam or the rights of the public.”

Russia

Caspian Sea

Georgia

Black Sea

Armenia

Azerbaijan

Turkey

AZ.

Predominantly

Kurdish

regions

Iran

Syria

Damascus

Baghdad

Iraq

Saudi Arabia

Jordan

Kuwait

In Iran, any independent or opposition voice is vulnerable to arrest or harassment.

More than 60 journalists have been detained in recent weeks as Tehran sought to silence coverage of mass protests over the death in custody of Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old Kurdish woman arrested for not fully covering her hair with a hijab. Several of the journalists arrested are Kurdish or work for Kurdish media.

But Kurdish journalists further risk being accused of links to the pro-Kurdish militant organization Free Life Party of Kurdistan (PJAK) or of promoting secession.

The PJAK has links to the Turkish militant group PKK and has been in an armed struggle with Tehran for nearly two decades. Iran designates it a terrorist organization.

Accusations of promoting the PJAK were leveled at Jafarimehr in 2020 when security agents raided her family home and questioned the journalist about her work.

Authorities detained the co-founder of the literary J-Magazine for 17 days, and guards laughed when she asked for a lawyer. She believes the arrest was linked to her magazine.

“Recognizing identity was the spark” for J-Magazine, Jafarimehr said. After decades of trying to assimilate Kurds, Iran “did not expect such a serious and independent magazine.”

Nationwide assault

Shaho Hosseini, a Germany-based analyst of Kurdish affairs, believes Iran targets Kurdish media because of the role they play in political mobilization.

During hardliner President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s rule from 2005 to 2013, several Kurdish publications were closed.

“It was much more serious in Eastern Kurdistan because Kurdish publications had a significant impact on culture and fostering a Kurdish perspective to issues that affected the Kurds’ nation,” Hosseini said, using the unofficial name for a predominantly Kurdish region in northwestern Iran.

“Iran wants to erase Kurdishness from those areas in any way possible. It wants to assimilate Kurds in those areas however it can.”

Jahan Fard, who was chief editor of J-Magazine, was more direct: “Iran wants to erase Kurdishness from those areas in any way possible. It wants to assimilate Kurds in those areas however it can.”

VOA submitted emailed questions to Iran’s Foreign Ministry and its United Nations office in New York. Neither responded. A follow-up email to Iran’s U.N. mission was returned as “undeliverable.”

Tehran does offer state-run channels in Kurdish, including Sahar TV. But Jahan Fard dismisses those as a poor source of news.

“Iran wanted to send an international message that Kurds in Iran have rights,” he said.

“But if you really watch those [state-owned] channels, you would not find anything substantial apart from demeaning Kurds.”

A VOA review of Sahar TV’s news website in October found the site focused primarily on international issues from Iraq.

For domestic news, the site included an article on a parliamentary investigation into Amini’s death that absolved Iran’s “morality police” of responsibility.

The main news page carried other government statements but no reports specifically focused on domestic Kurdish issues or protests that have spread across Iran in recent weeks.

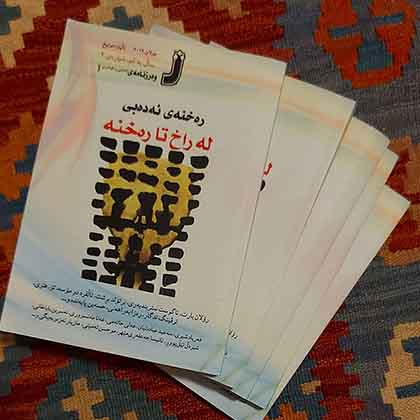

Copies of J-Magazine, a culture publication founded by Jafarimehr and Jahan Fard. (Jahan Fard)

Forced out

With diminishing sources for independent Kurdish-language news, journalists like Jafarimehr and Jahan Fard wanted to find a way to preserve their culture.

Jahan Fard

Editor of J-Magazine

Jahan Fard

Editor of J-Magazine

The chance to “reconnect the people of the area with their language” is the impetus behind J-Magazine, Jahan Fard said.

The magazine’s founders expected a struggle, but not a raid on Jafarimehr’s home nor that both journalists would have to flee.

Jahan Fard left first.

He had previously been arrested and harassed for his articles and books on Kurdish culture. But Iran’s response to his arrest in Turkey in 2017 was the turning point.

That year, Jahan Fard traveled to Turkey to attend a seminar and meet with publishers.

But Turkish authorities accused him of belonging to the PKK and took him into custody.

At the time, Ankara was arresting dozens of journalists as part of its response to a failed attempted coup.

Jahan Fard spent four months in a prison in the predominantly Kurdish city of Mardin.

After his release, Jahan Fard was deported. Back in Iran, authorities subjected him to prolonged interrogations.

No longer feeling safe, Jahan Fard worked with the advocacy organization PEN International to find a way to seek asylum and in 2018 moved to Germany.

From there, he worked to establish J-Magazine while Jafarimehr remained in Iran, studying for a master’s degree in linguistics.

“It gave me a special power,” said Jahan Fard about their joint effort. “It was like two loves in one: a love for your homeland and a love for your partner, all coming together.”

“We wanted people to think about their identity and be proud of their Kurdishness. We wanted them to see that the Kurdish language can be the language of serious literary work,” Jahan Fard said.

J-Magazine published only three editions in Iran. After the first two volumes, Jafarimehr said, authorities told her to “cease producing the magazine.”

And it was hard to find a printer who could produce the magazine without risk.

The third edition was printed in Europe and was available in Iran only digitally.

The couple eventually discontinued J-Magazine but continue to write about Kurdish-Iranian culture.

In 2022, a selection of their work was included in a German-language book titled “In the Never-ending Amber Night: Voices from Exile.”

For Jafarimehr, her arrest and security raid on the family home underscored her vulnerability as a journalist.

When authorities released her pending trial, bail was set at about $8,300 (350 million Iranian tomans) — the amount is roughly equal to an annual average salary in Iran, where the country is struggling under international sanctions related to its nuclear program.

The family home was put up as collateral and Jafarimehr was placed under a travel ban.

Meanwhile, Jahan Fard was working with PEN International to secure a German visa for her. They just had to wait for the right moment.

That moment came six months later, when the travel ban was lifted.

“It takes some time for them to extend the ban if they want to,” Jafarimehr said.

It was a short and uncertain window in which to act. But Jafarimehr took her chance and was able to fly to Europe.

But her parents and siblings were left behind.

For some journalists, exile can make their relatives more vulnerable.

The country has a reputation for detaining those it sees as opposing the regime. And it doesn’t give up, even after someone has fled.

In 2020, Iranian journalist Ruhollah Zam was lured to Iraq and forcibly returned to stand trial. A court sentenced him to death.

It is a tactic also attempted against VOA Persian host Masih Alinejad, who was the target of an elaborate plot to kidnap her from the U.S.

A new trial is scheduled for Jafarimehr’s case in 2022. But she won’t be attending. In leaving, she joins an untold number of Iranian Kurds who decided life away from Tehran’s grip was better than remaining.

No official estimates exist for the number of Iranian Kurds to flee government persecution in recent years, though rights activists believe it to be in the thousands.

Many live in nearly a dozen camps in neighboring Iraqi Kurdistan. Others have taken refuge in Europe and elsewhere.

From there, they try to keep reporting for communities back home.

“It is difficult for anyone to be away from family and land,” said Jafarimehr, adding that Kurdish identity is what can lead to someone being detained.

But, she said, “seeing the amount of energy and money [Tehran] spent on detaining journalists, writers and activists,” is what motives her to keep going.