Cause of Death

Migrant Workers and the 2022 Qatar World Cup

Thousands of workers died during Qatar 2022 World Cup-related construction, far more than in the run up to every other World Cup or Olympic Games in the past 30 years combined. This short documentary mixes firsthand accounts from families of the deceased in Nepal, explaining how so great a tragedy surrounds so celebrated an event — with no governments, organizations or companies taking responsibility.

Khajuri, Nepal

Ramesh Gupta

“Football is one of the most popular games in the world.

“When I play, it makes me so happy.

“We play against the local teams. And everyone is celebrating when we win the game.

“To celebrate, we take pictures of ourselves with the trophy. And later on we also receive some cash prize. With that money we throw a party for the boys. That’s it.”

Archive 2010 VOA News report

“Certainly the most surprising decision was the 2022 victory by Qatar, to become both the first Middle East nation and the smallest nation to host a FIFA World Cup.”

Archive 2019 VOA News report

“An estimated two million migrant workers are in Qatar, mostly from South Asia and Africa. There were widespread complaints of unpaid wages, dire living conditions and dangerous construction sites.”

Gianni Infantino, FIFA president

“All the stadiums, they are state-of-the-art, they are beautiful.”

Sepp Blatter, former FIFA president

“But in no way can FIFA accept to be responsible for the welfare of workers, they belong to commercial and industrial companies of other countries. We couldn’t do that.”

Ramesh Gupta

“I am from Nepal. My uncle passed away three and a half months ago in Qatar.”

Dr. Parkash Raj Regmi, cardiologist in Nepal

“We find coffins with dead bodies arriving to Kathmandu airport.”

Urmila Devi Sah

“My husband died in Qatar four months ago.”

Hiralal Pasman

“I had a son who passed away.”

Aslani Devi

“He died in Qatar.”

Shekh Akhtar Husen

“My father called me with the news and asked me to come home right away. I couldn’t believe it and I said, ‘I talked to him this morning.’ ”

Sakhil Saphi

“He told me that his ticket home was booked for next month. But the next morning at 4 o’clock he was found dead.”

Kaushalya devi Bin

“I have lost my son. What else is there to say?”

Ramesh Gupta

VOA News

“My name is Ramesh Gupta.

“Our team name is Shree Mahabir Sports Club.

“If I had the opportunity to stay in my village, then I would like to start a small business. We have a shop here that I would expand.

“The government has not been able to provide enough employment opportunities for all of the people here in Nepal. So, because we have no choice, in order to earn a living, to live our lives and to secure a future we are forced to go abroad.

“I’m not sure what work I will get overseas. It’s not determined yet. But, given my abilities, it would be good if I could work in an office. Or, I would like to work as a cashier.

“Yes, I do get scared. The work we do abroad is like that.

“We have to work at building construction sites, and we don’t know what might happen.

“Whatever work people can get, they do it. Since we don’t have proper education, whatever work we get, we have to do.

“A lot of people have died in Qatar.”

VOA News

In 2010, when Qatar clinched its bid to host the 2022 FIFA World Cup, the controversies began.

The tiny Gulf country didn’t have the infrastructure in place to host the World Cup.

Qatari representatives were accused of bribing their way to securing the Cup. Investigations into alleged corruption continue more than a decade later.

There were complaints summer heat- sometimes soaring to 50 degrees - was too much for fans and players. That was solved by moving the games to the winter.

And while wealthy, Qatar has virtually no native construction workers. But over the next 10 years the population of foreign workers grew, adding more than 65% to the foreign population.

The influx meant the already fraught system of hiring abroad for labor would be put to the test. And it was.

Construction boomed: a $300 million renovation of its Khalifa International Stadium; seven new stadiums; and a new luxury city – Lusail, where the Lusail Iconic Stadium will host the World Cup finals.

Qatar now boasts more than 100 new hotels and serviced residences, new skyscrapers, entertainment plazas, museums, public art works and a complete new metro and tram system.

As quickly as all those buildings rose, so, too did reports of human rights abuses of the people who were building them.

Human rights groups, including Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, as well as news media reported that workers were subjected to wage theft and restrictions on their movement. Most egregiously, they said, workers suffered from dangerous working and living conditions.

Thousands of workers died during Qatar 2022 World Cup-related construction, far more than in the run up to every other World Cup or Olympic Games in the past 30 years combined.

A 2021 Guardian Newspaper investigation revealed more than 6,500 deaths of migrant workers in Qatar since the World Cup was awarded.

Amnesty International says most death certificates list “natural causes” or “cardiac arrest,” as the cause of death, causes that shift blame, and liability, away from employers.

Ramesh Gupta

“My brother brought back the body. He was living in Qatar. There are many people from this village in Qatar. They all helped him. The people who were living there had raised about 300,000 Nepalese Rupees to bring his body back here. Everyone pitched in.”

Urmila Devi Sah

VOA News

“My name is Urmila Devi Sah.

“My husband died in Qatar four months ago.

“I have four children. My oldest son is 15, 16, the others are ten, eight and five-and-a-half years old.

“Sometimes I wake up at 6 a.m., sometimes at 5.

“First, I clean the house, the shop and the yard. Then I open the shop. After that, I wake up my sons and make tea and a light breakfast. I serve my family members and then I cook a meal.

“After cooking, if I have other work, I do it. If not, I run the shop in the afternoon.

“I opened the shop three or four months ago for support. But it doesn’t generate much income. From the income, I purchase goods for the shop. To date, I have not made enough for household expenses.

“My husband worked as a painter. He used to go to work at 9 a.m. and return around 6 or 7 p.m.

“I talked to my husband a few hours before his death. He told me that he was feeling pain in his chest after he attended a party. He endured the pain for three or four days and was taking medicine.

“Later, he died of cardiac arrest on his way to a hospital there, they said.

“When I heard about his death, my mind stopped working. My whole family was crying.

“When I knew he was no more, I thought about what to do. I could do nothing if he was no more.

“Everyone started weeping and crying.

“Whenever I remember my husband, I can’t stop tears falling from my eyes.”

Dr. Prakash Raj Regmi, cardiologist in Nepal

VOA News

“But what we see every day, we find coffins with dead bodies arriving to Kathmandu airport.

“How can it be a natural death? Either it should be an injury, either it should be some serious illness.

“How can a person, 20 years old, die naturally?

“Of course now, if we go beyond the death if we try to explore the cause of death what were the causes of death? What were the triggers that caused the complication so that a person died?

“The non-cardiac death, if we evaluate then there are several: work injuries, fall from height, there are poisonings, there is homesickness, leading to depression and suicide.

“And this extreme atmospheric condition where the workers work the day long. It causes dehydration. It may cause heat stroke. It may cause massive dehydration, electrolyte imbalance. And this may lead to death.

“Sweating is a defense mechanism. It cools the body. But when the person is exposed to extreme hot climate for a long duration of time this mechanism, body mechanism, fails. The sweating cannot cool down the body. So the temperature of the body rises and this leads to several complications which may later on cause death.

“Death may occur immediately at the spot. Or it may occur several hours or days later.”

Ashmita Sapkota, Amnesty International Nepal

VOA News

“Because their deaths are unexplained, not investigated properly, as a result, the families are denied compensation. And also they do not know how their near and dear one died in Qatar.

“It could be heat and it could be because of the pressure, the suicide rate is also very high, because they take loans they must have a lot of mental pressure also.”

VOA News

Despite the danger, workers keep traveling to Qatar for the chance to work. Most come from India, Nepal, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, also the Philippines, Kenya, Sudan, Uganda and Nigeria, countries where jobs are scarce and poverty is rampant.

In Nepal, one of Asia’s poorest countries, 56% of households receive remittances from these workers abroad – that’s more than half the country dependent on their income.

The death of a family’s main earner can be devastating. If a worker is deemed to have died due his job, his family is compensated financially. But if his death certificate says he died of “natural” causes or other non-work-related reasons, the family gets nothing from the employer.

And this is usually the case.

Some say the worker hiring process known as Kafala is the heart of the problem.

Ashmita Sapkota, Amnesty International Nepal

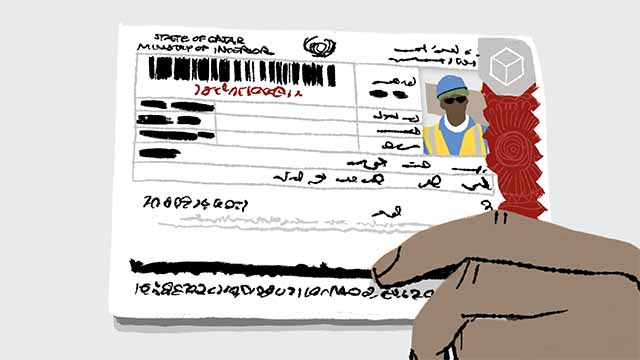

“Due to this Kafala system — which is also called the sponsorship system — the workers were tied to their employers, they were not allowed to switch their jobs and they were not allowed to leave the country without taking permission from their employer.

“As a result, migrant workers were forced to remain submissive to labor exploitation and abuses.”

VOA News

The Kafala system is a legal framework used in many Middle Eastern countries to help employers hire workers from abroad, usually for household help or manual labor, and puts the employer in charge of the worker’s legal and visa issues.

Under Kafala, workers need employers’ permission to enter the country, stay in the country, change jobs, and leave the country.

It’s a system so ripe for abuse that one Nepalese diplomat referred to Qatar as “an open jail.” Human Rights Watch said some of the abuses could amount to “modern slavery”.

Years of criticism of harsh working conditions, low or no pay, and deportations because employers withheld documents led Qatar to implement reforms starting in 2017, and officially dismantle the Kafala system.

Among the improvements have been a set minimum wage - 1,000 Qatari Rials a month [about $275] - and a stipend for food and housing. That standard appears to be generally upheld.

Workers officially no longer need their employers’ permission to travel or change jobs. But many people say they still need to seek that permission — often for fear of retribution. Others who want to leave can’t, as they owe large sums of money to lenders who helped them pay recruitment companies.

And they still have no right to join unions or participate in strikes. Three months before the games, a local advocacy group reported 60 workers were detained, some of whom were deported for protesting unpaid wages, according to the Associated Press. The Qatari government acknowledged arrests for “breaching public safety laws” but declined to provide details.

Ashmita Sapkota, Amnesty International Nepal

“So in the paper, Kafala has been dismantled but in terms of, if you see the practicality still it exists in Qatar.

“So, in my opinion, we think that FIFA and Qatar should establish and fund a comprehensive program to provide a remedy to the migrant worker who faced exploitation and abuses for the last twelve years that went unaddressed.

“And it should not be limited to migrant workers who worked in stadiums or in the training sites but also other workers who were deployed in preparation for the delivery of the tournament.

“We continue to receive cases from migrant workers through phone calls, through emails complaining that they had not been paid for the last few months and also some workers, they complained that they had been underpaid or they were not paid for overtime.”

Ramesh Gupta

“We go abroad because we are not getting any work here. Otherwise, we would want to stay in our own villages and do something for our country.

“If I go now, then I think I will stay there for a minimum of two to three years. And after I come back, I will think about what I will do.

“I will have to support my mother, my father, and my elder brother. Until now, my brother has been doing everything for me. So, now I will have to support them as well.

“People go there for work and if some kind of accident happens to them, then it’s a sacrifice.”

Aslani Devi

“We had small children at that time. So, my husband decided to go for foreign employment to earn money for the food and their schooling.

“He called me on the phone everyday.

“He had to climb high buildings and work hard there. He had to carry construction materials up to the top of those buildings.

“We were told he died the next morning when his friend called me. He passed away at night.

“His body was brought here 15 days after he died. After that, we performed his last rites and rituals at our home.

“I have no source of income since my husband’s death. I sold my one katha [338 m2] of land and I am running my home from the money I got from the sale.

“I sometimes feared he would die abroad.”

Sukhi Mukhiya

VOA News

“My son was paid six kilograms of [unshelled] rice a day here. I heard from others he was willing to go abroad for work but I told him not to go.

“We had to take out a loan to send him abroad. We had to ask for loans from the other villagers.

“He went there as a painter to paint houses. But when he got there, he was forced to work as a laborer using a shovel.

“He said the work was very difficult and that the employment agent betrayed him.

“He said, ‘I want to come home.’

“He went there with loans. So he wanted to pay off the loans and come back home.

“He was just getting 300 Qatari Riyal per month for his work. He said that he will first pay back the loans and then come back.

“After repaying the loans he said, ‘I will come back now.’ So I told him to come back soon.

“His roommate called me and said that Jit Narayan had passed away.

“We were shocked.”

Sakhil Saphi

VOA News

“I went abroad because my family was in debt and we were struggling financially.

“My brother was already in Qatar and he arranged my passport and told me to come there for work.

“A month ago, he told me he was going to come home soon, but the next night at 4 a.m. he was found dead.”

Dr. Prakash Raj Regmi, cardiologist in Nepal

“And they are forced to work for a longer period during the daytime. They are more exposed to the outdoor heat. The living conditions are poor. The healthcare system is not that good. As it should be. So all these factors are causing the rise in death in these workers.”

Urmila Devi Sah (speaking in Maithili)

“He was good natured. His voice and behavior were also so nice. We had very good relations. He never quarreled or fought with me. He was not rude. He was a good guy.”

Ramesh Gupta

“My village is a very beautiful place. I find it beautiful. I don’t feel like leaving my village and going somewhere else.

“While I can stay in my village, I want to play football with my friends. Football is my favorite game.”

Qatari World Cup officials declined VOA interview requests but issued a statement saying their “commitment to ensuring the health, safety and dignity of all workers employed on our projects has remained steadfast.”

They say just three people have died in World Cup work-related accidents since 2014.

Just prior to the start of the World Cup, Qatari officials removed hundreds of workers from Doha.

Though officials claimed they had been giving adequate living conditions, critics say Qatar tried to remove the spotlight from the migrant workers during the tournament.

Sepp Blatter, the former FIFA president who oversaw the vote for the 2022 World Cup host country, has since called the selection of Qatar “a mistake.”

Credits

Editing

Animation and Graphics

Producers

Special Thanks

Yolanda Lopez

Leslie Washington

Walid Ghariani