Water's Edge

A Shrinking River Threatens the U.S. Southwest

A Jet Ski rides past Lake Mead’s “bathtub ring,” mineral deposits that show how far the water level has dropped. The lake hit a record low in July. (Steve Baragona/VOA)

By Steve Baragona

The desert sun beats down from a cloudless sky as Las Vegas landscaper Mat Baroudi roars across Lake Mead in his motorboat.

It’s hot. The lake is the perfect place to be on a scorching Nevada morning. Baroudi loves coming out here with his son to fish and swim. But for the last few years, they have watched the lake shrink from under them.

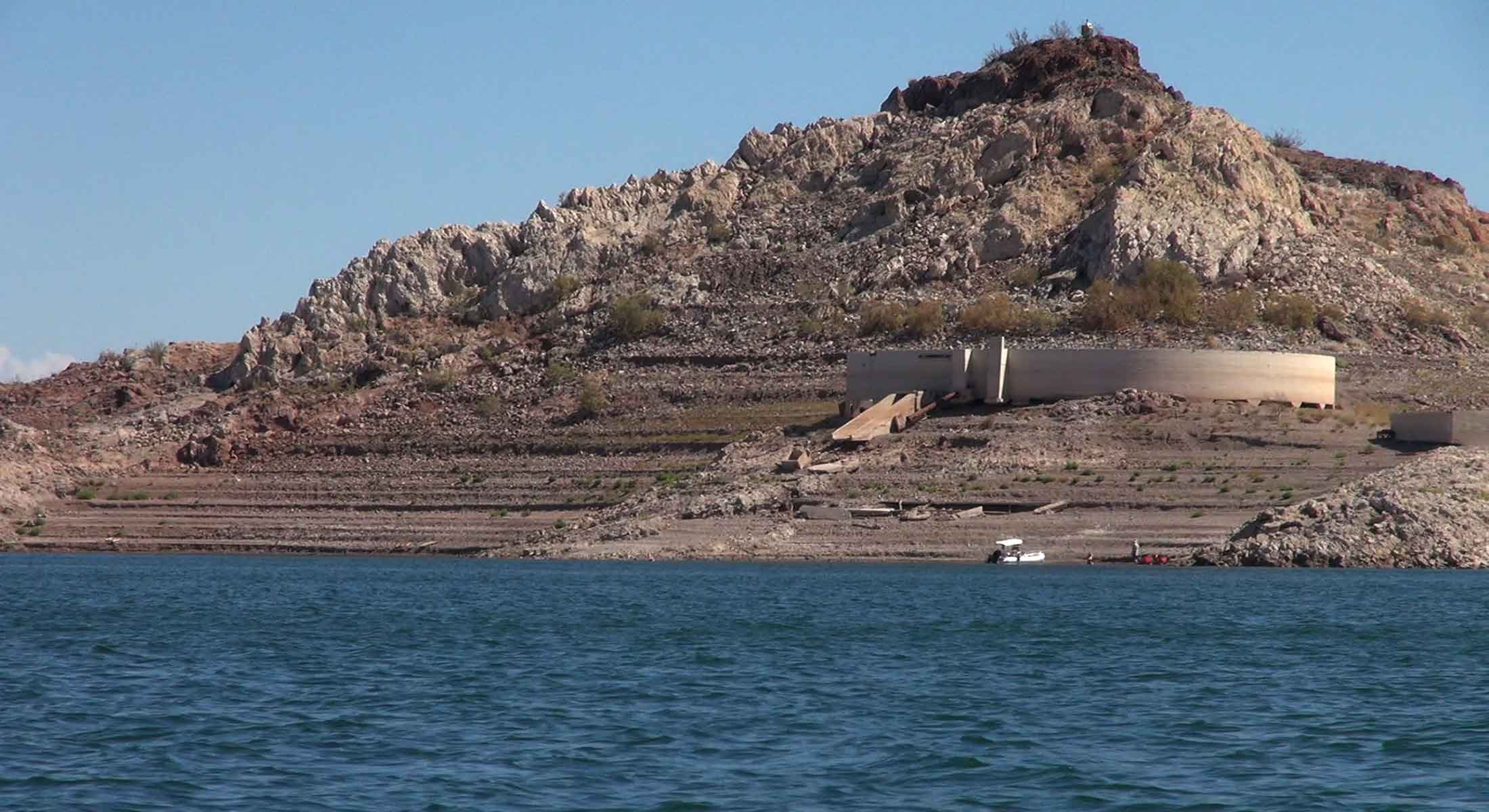

To get an idea how far the nation’s largest reservoir has fallen, consider this: What was once one of Lake Mead’s top scuba-diving spots is now halfway up a dry hillside.

“Every time we come out here, we’re shocked by how much water’s missing,” Baroudi shouted over the roar of the engine.

To get an idea how far the nation’s largest reservoir has fallen, consider this: What was once one of Lake Mead’s top scuba-diving spots is now halfway up a dry hillside.

Baroudi steers the boat past an island with a squat, beige cylinder the width of a basketball court. It looks a bit like a concrete UFO. It was part of the plant that churned out 4,360,000 cubic yards of concrete to build Hoover Dam, a couple miles over the hills to the southeast. The plant disappeared into the murky depths in the 1930s when the dam was completed and the reservoir filled.

“Now look at it,” Baroudi said. The structure sits beached on a rocky outcrop looking down on the lake it helped create. Reaching it is no longer a dive. It’s a climb.

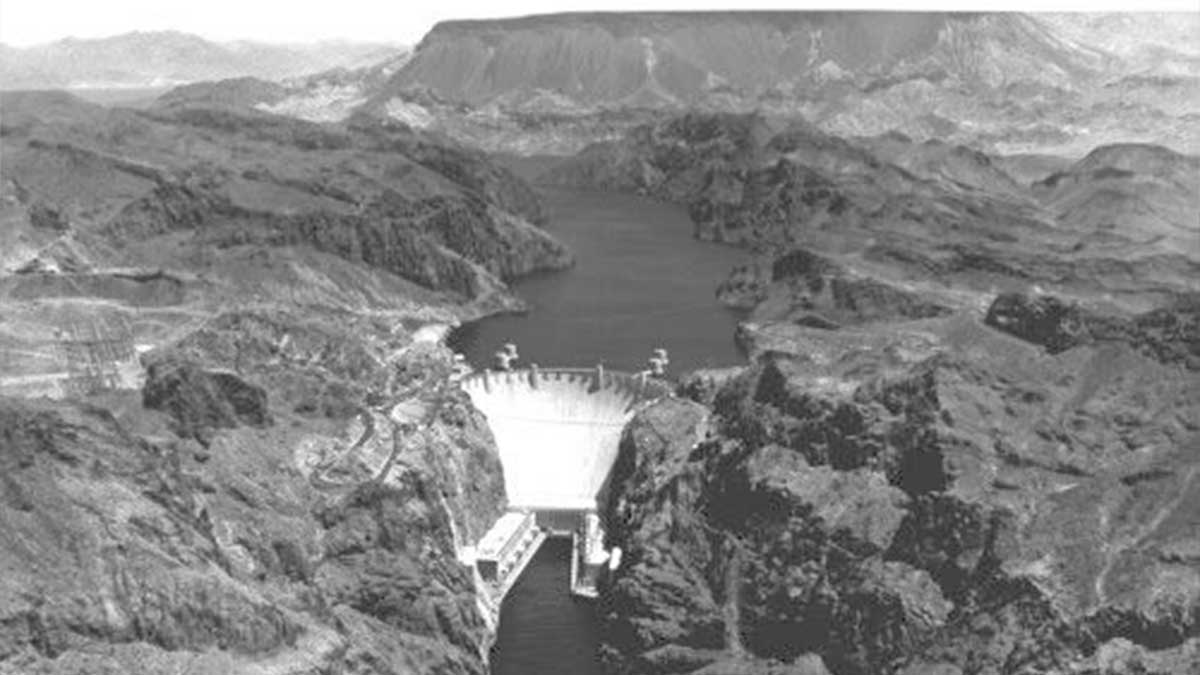

Hoover Dam was built to store the waters of the fickle Colorado River, taming floods, relieving droughts and pouring life into the desert southwestern United States.

Lake Mead anchors the lower half of the river basin, a system that provides water to nearly 40 million people in seven U.S. states. Cities from San Diego to Denver drink from the Colorado. The river irrigates more than 5 million acres of farmland, including California’s Imperial Valley and Arizona’s Yuma County, two areas that supply the nation with most of its vegetables through the winter season. Both would be barren without its waters.

As Lake Mead recedes, it has left a white stripe of mineral deposits 14 stories tall across the brown and red rock walls, as if to underline a question: Have we overreached?

Scuba divers used to swim down to this section of the old concrete plant that helped build Hoover Dam. Parked at the water's edge, boaters can be seen beginning the climb up to it. Only the brown tip of the island is above water when Lake Mead is full. (Steve Baragona/VOA)

From North Africa to Southeast Asia, many of the world’s key river systems are being stretched to their limits. In a 2012 report, U.S. intelligence agencies said fresh water supplies along the Indus, Mekong, Nile, Tigris-Euphrates and other river systems will not keep up with demand in the coming decades. Food security, economic development and regional stability are all at risk, it warned.

The same is true for the Colorado. The river touches nearly every aspect of life in the Southwest, said Pat Mulroy, former head of the Southern Nevada Water Authority and currently a senior fellow at the Brookings Mountain West research institution.

“You have some of the largest Western cities — some of the largest American cities — that are critically dependent on this water supply,” Mulroy said. “You have some of the most productive agricultural areas…. You have some of the grandest national parks. You have any number of [Native American] tribal nations. You have an enormous hydropower production. And you have an obligation to deliver water to the country of Mexico. I mean, this is a system that can’t fail.”

Arizona State University researchers calculated that the river supports 16 million jobs, generates $870 billion in income for workers and contributes $1.4 trillion to the region’s economy.

But after 14 years of drought, the system is closer to failure than ever.

This summer, Lake Mead hit a record low. At 1,080 feet above sea level, it was less than 40 percent full and just 5 feet from the point at which water authorities must cut deliveries downstream for the first time ever. Winter rains have raised the lake a few feet. But forecasts are not looking good. A cut is expected as soon as 2016. Farmers in central Arizona would take the first hit.

A 30-foot drop, to 1,050 feet, threatens the equipment that generates enough hydroelectricity to meet the needs of 1.3 million people in Southern California and beyond.

At 1,000 feet, the lower water intake for the city of Las Vegas sucks air. The city is building a “third straw” to draw water from the bottom of the lake, at a cost of $817 million.

The reservoir hits “deadpool” at 895 feet. Below that point, water no longer flows out of the lake, leaving users in California, Nevada and Arizona dry.

The Hoover Dam was built in the 1930s to control the Colorado River and store its waters. But from the very beginning, experts overestimated how much water the river could provide. (Courtesy of U.S. Bureau of Reclamation)

The lake sits in a V-shaped basin, narrower at the bottom than the top. That means the lower the water level gets, the faster it drops.

The current drought is already the worst in a century of recorded history. But tree-ring records and other proxy climate data going back more than a millennium show it could still get much worse.

“That region has experienced extended droughts, much longer than the current drought,” said Debra Knopman, principal researcher at the RAND Corp. “These droughts can persist for decades, in fact.”

Even when the drought does end, the region’s water troubles will not. They started even before Hoover Dam was built.

When a 1922 law divided the waters of the Colorado River among the seven basin states, hydrologists had just a few short decades of data on how much flowed in the river.

“Lo and behold, it turns out that that was a period of high flow,” Knopman said.

The river has rarely delivered that much water since. As a result, every drop of its water is spoken for, and then some. And cities that drink from the river continue to grow.

“All the users on the system live on the razor’s edge,” said Kathryn Sorensen, water services director for the city of Phoenix. “We use everything that’s available to us every year. And what that means is, we’re not leaving water behind to prop up levels in Lake Mead to provide for resilience in drought, megadrought [or] climate change.”

And that’s a problem, she said. Most models show the region getting warmer and drier through this century, and droughts will get longer and more severe.

One 2008 study gave 50-50 odds that Lake Mead would hit deadpool by 2021.

City managers across the region face a cardinal challenge: find more water.

Native Americans, Las Vegas battle over water

The drive to the Goshute Native American reservation: laser-straight and dry. (Steve Baragona/VOA)

By night, the Las Vegas Strip sparkles like a sequined jumpsuit.

Marquee lights flash and giant LED screens blaze along the six-kilometer constellation of casinos, hotels and shopping malls. This is the Las Vegas of legend. It’s a big part of what draws 40 million visitors to the city each year.

But from the hills outside the city, the shimmer of the Strip is swallowed up by a shining sea of suburbs. After two decades as the nation’s fastest growing metro area, Las Vegas now sprawls across 500 square miles. The population has nearly tripled since 1990. Three-quarters of the population of Nevada lives in the Las Vegas area. It generates 70 percent of the state’s gross domestic product, including $6.5 billion in gambling revenue on the Strip alone.

Just west of Lake Mead, Las Vegas has nearly tripled in population since 1990. Meanwhile, the lake has fallen to a historic low. (Data provided by Google, USGS)

The unprecedented growth of this desert oasis would not have been possible without Lake Mead, just over the hills to the east. Ninety percent of the city’s water comes from this one overburdened, dwindling source.

Las Vegas urgently needs to diversify.

To the casual observer, the Goshute Native American reservation is not a promising place to look for water.

The road to the reservation, 275 miles north of Las Vegas, runs laser-straight through wide-open valleys of dry grass and scrub. The hills run the full spectrum of browns and grays, lit orange and gold by the setting sun.

It’s breathtaking. But it’s dry. The name “Goshute” means “desert people” in the tribe’s Shoshone language.

There is water to be found here, however.

Former tribal chairman Ed Naranjo leads the way through a patch of fragrant sagebrush to a clear, cold spring rushing out from under a hillside. Bonneville cutthroat trout swim in the currents. The water disappears in spots under a carpet of watercress.

Former Goshute tribal chairman Ed Naranjo fears for some of the tribe's sacred places. (Steve Baragona/VOA)

An underground aquifer feeds this spring. It’s the water underneath this valley and four others nearby that has drawn the attention of Las Vegas. The Southern Nevada Water Authority plans to tap these aquifers through a multi-billion-dollar pipeline supplying the growing metropolis to the south.

But Naranjo says pumping water from this desert valley would be the end of the Goshute people.

“We’ve been here for years living on the desert, and we’ve adapted,” he said. “But you can push it only so far [before you] just can’t continue to live.”

There is virtually no industry here. One of the tribe’s few sources of income is selling permits to visitors to hunt elk that live in the mountains. If the water table drops and the springs and vegetation dry up, “the elk are going to move elsewhere,” Naranjo said, “and that’s going to be one hell of an impact on our tribe.”

Not to mention the impact on some of the tribe’s most important spiritual sites.

Federal troops killed Goshute Native Americans on this site in the late 19th century. Goshute legend holds that where each of their people fell, a cedar tree grew. They say Las Vegas's plan to pump groundwater threatens this sacred grove. (Steve Baragona/VOA)

Along a lonely stretch of the Grand Army of the Republic Highway 300 kilometers north of Las Vegas, a narrow strip of swamp cedar trees stands out against the expanse of brown and gray. Goshute blood was spilled here in late-19th century battles with federal troops — massacres, the Goshutes say.

Where each of their people fell, Goshute legend holds, a cedar tree grew. This grove is a sacred place to honor their ancestors.

Pumping the water under these trees would destroy this hallowed ground, Naranjo said.

It’s not just the Goshutes concerned about the pipeline. Farmers, ranchers and small towns in the valleys depend on the underground aquifers.

Tom Baker’s center-pivot irrigators paint half-mile-wide circles of green alfalfa in the desert sand. Three generations of Bakers have raised cattle and crops here in Baker, Nevada, population 68.

Farmer and rancher Tom Baker (Steve Baragona/VOA)

“Water is the basis for everything we do,” Baker said. “Without water, the land here is, in ways, virtually useless. If we have water, it can be incredibly productive.”

But Baker said he’s not even sure pumping water to irrigate his crops is sustainable, let alone supplying Las Vegas.

And then there’s the impact on the fragile desert ecosystem.

Baker said drawing down the water table will dry up much of the deep-rooted vegetation that survives here. And he said the soils in many areas may be too harsh for even the hardiest plants to tolerate.

Many worry the area will become a dust bowl.

“It’s a huge experiment over a huge area,” Baker said.

The view from Las Vegas

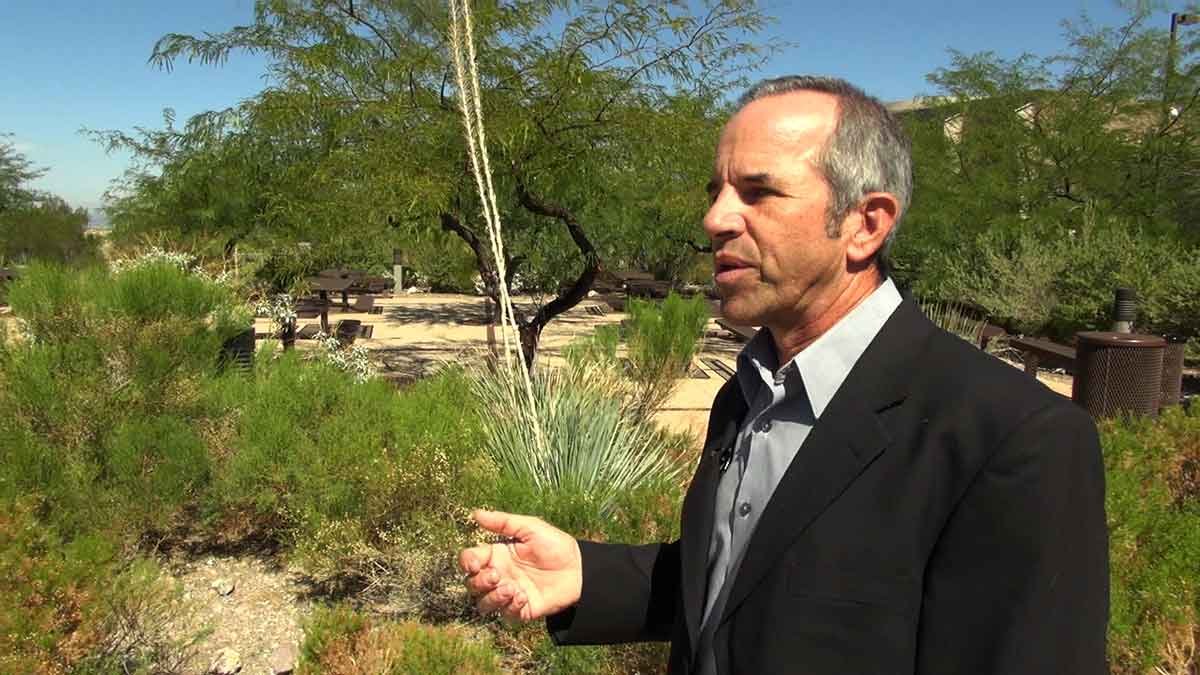

Pat Mulroy spent the last quarter-century securing Las Vegas’ water supply. She retired as head of the Southern Nevada Water Authority last February after fighting for the pipeline since 1989.

But, she said, Las Vegas is not out to steal the valleys’ water. According to Mulroy, the project can supply the city without destroying the livelihoods of farmers, ranchers and Native Americans.

“I don’t think we would ever have embarked on it if we didn’t know that it was possible,” she added.

“There is nothing that would justify Southern Nevada having water at the expense of its neighbors in the north.”

Opponents have the wrong idea, she said. These groundwater sources would be a safety net, not a regular supply, to be used only in years when the Colorado River falls short.

Environmental law limits the amount of water the city can take and how much damage pumping could do, Mulroy noted. The project would be closely monitored, and the water authority would be required to protect sensitive areas and recharge aquifers it depletes.

As she sees it, climate change and growing populations mean many cities around the world — not just in the U.S. Southwest — are going to have to spend a great deal of money to build networks of water sources they won’t be using every year.

“There is nothing that would justify Southern Nevada having water at the expense of its neighbors in the north.” — former Las Vegas water chief Pat Mulroy

“We’re going to have to use water supplies as they are available,” she said. “We’re going to have to let groundwater basins rest. We’re going to have to do a lot of artificial recharge when Mother Nature gives us that opportunity. And certain parts of our system are going to sit dormant for certain years.”

The conflict between Las Vegas and the northern valleys has deep historical roots, Mulroy said.

The cautionary tale on many rural Nevadans’ minds is California’s Owens Valley, which dried up when Los Angeles diverted its water supply in the early 20th century.

But in Mulroy’s view, urban and rural residents don’t have to be enemies. Cities can build the infrastructure to recharge groundwater basins in rural areas, which don’t have the money or the know-how.

“If I’m a rural Nevadan, I can’t picture that,” she said. “When I look into my rearview mirror, all I see is a threat.”

But Mulroy said everyone is going to have to give some in order to meet the coming demands. That includes the environment, she says, and the groups defending it.

“If we all have to give to be part of the solution, so must they,” Mulroy said. “They can’t expect the natural environs in a changing world to stay unchanged. And they have to get beyond protection to mitigation. And they have to find a way to partner with urban areas.”

Former Las Vegas water chief Pat Mulroy says opponents of the pipeline have the wrong idea. (Credit: Steve Baragona)

But valley residents do not trust authorities in Las Vegas.

Ed Naranjo is not convinced the water authority would ever turn the pipeline off after spending billions of dollars to turn it on. And he doesn’t put much faith in the city’s ability to restore the water it takes.

“We’re in a drought, everybody knows that,” he said. “Do you stop and think, ‘Wait a minute, how are we going to recharge this?’”

The Colorado River depends on snowfall far upstream in the Rocky Mountains. But there hasn’t been much snow in recent years. And climate change likely will bring even less.

“Nobody can say, ‘OK, we’re going to have a heavy winter, we’re going to replenish it, there will always be water,’” Naranjo said. “That’s not going to happen.”

The courts have so far sided with the valleys. But the appeals continue.

It may be years before the issue is settled. Meanwhile, the drought drags on, raising the stakes for Las Vegas.

But the city known for extravagance has a surprisingly thrifty side.

Las Vegas pulls grass to save water

Despite restrictions, waste from lawn sprinklers is easy to find in Las Vegas. (Steve Baragona/VOA)

Las Vegas is a city that does not like to skimp.

Take the fountains at the Bellagio hotel and casino, one of the top attractions on the Strip. Crowds gather around the 8-acre artificial lake to watch water dance from a thousand sprayers to the music of Elvis Presley and Luciano Pavarotti. Jets shoot tens of thousands of liters of water up to 460 feet into the desert sky.

“No one is using this grass for anything. It’s just there. And it’s just soaking up all this water.” – Mat Baroudi, Las Vegas Landscaper

For a city whose water supply is vanishing before its eyes just a few miles away, this may seem like slow-motion suicide. But the fountains are supplied by a private well, not Lake Mead, and all the water is recycled.

And the Bellagio’s fountains are a drop in the bucket compared with the real water hogs: suburban lawns.

Every square foot of grass guzzles more than 73 gallons of water per year in the dry desert heat. That’s roughly 30 times more than the city gets in rainfall.

For landscaper and Lake Mead boater Mat Baroudi, lawns are more than just a waste of water. They’re a waste of space.

A textbook rectangle of lush, green grass fronts the home three doors down from his. “No one is using this grass for anything,” he said. “You don’t see any kids out here playing on it. You don’t see anybody sitting out here with a blanket and a picnic basket like we’re in 1955. It’s just there. And it’s just soaking up all this water.

“It’s a huge waste of our resources,” he said. “And the lake is down to 39 percent right now.”

The lawns in Baroudi’s neighborhood and around the region are a remnant of the city’s enormous growth spurt in the 1990s, when Las Vegas was the fastest-growing metropolitan area in the nation. It grew by more than 85 percent that decade, nearly twice the rate of the next-fastest growing city, Raleigh, North Carolina.

New arrivals from cooler, rainier parts of the country brought with them the idea that a house needs a lawn. And builders covered the exploding suburbs in grass because it was quick, easy and cheap. “You literally in a matter of hours can turn something from dirt to an emerald-green lawn,” said conservation manager Doug Bennett with the Southern Nevada Water Authority. “Just add water.”

Homes, supermarkets, convenience stores — everything got a carpet of green grass, Bennett said. By the early 2000s, city officials realized this was a bad idea.

Landscaper Mat Baroudi, owner of An English Gardener, believes lawns are a waste of resources. (Steve Baragona/VOA)

“People were making these capital decisions about grass that really had long-term water demands that weren’t being addressed,” he said. “And we had to change that.”

Pat Mulroy was head of the water authority at the time.

“When the drought had really taken hold after 2002, we were strategic,” she recalled. “We said, ‘Let’s not lose this opportunity to make a fundamental change in how this community deals with its water resources.”

Front lawns were banned from new homes. And the agency began paying homeowners to replace their grass with something more desert-appropriate.

And that’s not just “rocks, a cactus and a dead cow skull,” Mulroy said.

Baroudi won an award for his yard. Trellises of dark green jasmine frame his front door.

“It blooms twice a year and it smells fantastic,” he said. “The whole street can smell it.” The plum tree around back produced more than 10 pounds of fruit. His family made jam with it. The whole yard is thriving on a tiny flow of water from drip irrigation.

A few blocks away, Baroudi and his company, An English Gardener, are transforming his neighbor Dasya Duckworth’s backyard from a high-maintenance patch of grass to a playground for her young son and outdoor living space.

“As much as you think you’re environmentally aware, having a child, I think, starts you fine-tuning that concept a little bit more,” she said.

And it occurred to her that “I live in a desert. And I have a green lawn. There’s something wrong with this picture,” she laughed.

SNWA will pay her $1.50 per square foot to rip out the lawn. That will cover about 10 percent of the remodeling cost.

Southern Nevada Water Authority Conservation Manager Doug Bennett is helping Las Vegas residents install landscaping suited to the desert climate. (Steve Baragona/VOA)

Since 2003, the utility has spent about $200 million to remove more 165 million square feet of grass.

The program locals call “cash for grass” is part of a package of aggressive conservation measures. Residents pay more for using more water. Nearly all of the water that goes down a drain gets reused, from car washes to toilets.

With these and other steps, Las Vegas now uses less water than it did a decade ago, despite its explosive population growth. Las Vegas cut annual water use by more than 29 billion gallons from 2002 to 2012, while the city added more than 400,000 new residents.

But Las Vegas still uses more water per person than its desert neighbors. And it still has a lot of grass that wastes a lot of water.

Driving through Baroudi’s neighborhood at dusk, lawn sprinklers switched on with a gentle hiss. A stream was already running across the street and down the gutter. It’s wasted water and, technically, it’s illegal. Homeowners could get a fine for this — $80 for a first offense, and up to $1,280 for repeat offenders.

Baroudi got annoyed. He pointed out the sprinkler overshooting the lawn and watering the driveway. Another aimed in the wrong direction.

As water streamed down the gutter, Baroudi shook his head.

“All in the effort to water some grass,” he said.

Meanwhile, downriver, efforts to water crops are drawing attention from leaders of thirsty cities.

Arizona fallows farms to save water for cities

Farmer Jim Weddle’s fallowed field shimmers in the southern Arizona heat. (Steve Baragona/VOA)

Farmer Jim Weddle turned off the water on some of his alfalfa fields last year. They didn’t stand a chance under the baking Arizona sun. Without water, the land is now as dry as the surrounding desert. Heat ripples off it in shimmering waves.

There would be no agriculture here on the mesa outside Yuma, Arizona without the waters of the Colorado River, stored behind the Hoover Dam 240 miles north. The farms form a tidy green grid against the great beige expanse of the Sonoran Desert.

But as Lake Mead shrinks, “you certainly worry about the future,” Weddle said. “The dams have been sustaining us for years, but they can only drop so far before there isn’t any more water to come out.”

Alfalfa grower Jim Weddle (Steve Baragona/VOA)

There’s plenty of Colorado River water here now, despite the drought. It rushes through the lattice of concrete-lined canals that crisscross the fields of alfalfa and citrus.

And Yuma’s farmers are under no obligation to give it up. They have high-priority rights to that water under Western water law going back more than a century.

But the Southwest’s cities are eyeing a drier future. Since agriculture uses about four-fifths of the river’s water throughout the basin, cities are looking to farmers for help.

So a pilot program in Arizona is paying farmers like Weddle not to grow a crop — and to save some water.

Weddle says it’s a good deal, for now.

But while cities are asking for water today, he worries that tomorrow they will be taking it.

Authorities expect that as soon as next year, they will have to reduce water deliveries from Lake Mead for the first time ever.

Yuma’s farmers would still get their water. The cut would fall first on farmers upstream who get water from the Central Arizona Project, a 336-mile canal system that carries Colorado River water across the state.

But the impacts of the looming cut are already rippling down to Yuma.

The canals also deliver water to Phoenix and Tucson, the state’s two largest urban areas, and officials only give the cities 10 or 15 years before their Colorado River supplies are affected, too.

Cities looking to replace their losses see fallowing farmland as an attractive, if temporary, option.

Central Arizona Project Assistant General Manager Tom McCann oversees a shrinking water supply. (Steve Baragona/VOA)

“If there’s a significant shortage and it’s impacting cities,” said Tom McCann, assistant general manager of the authority that oversees the project, “maybe in that year you go and say, ‘Hey, can we pay you, the agricultural user, not to use water this year so that we could have it for cities?’”

The authority is backing the pilot program that pays farmers like Weddle not to grow a crop.

The program is too small to have much of an impact. The point is to find out how much water fallowing an acre of Yuma cropland would save.

A lot of people would like to know. Four major urban water authorities in Arizona, California, Nevada and Colorado that depend on Colorado River water plan to fallow more ground as part of an $11 million program aimed at propping up Lake Mead.

But the Yuma deal is short-term, and Weddle wants to keep it that way. Farmers are wary of giving up too much to keep the cities afloat.

Any talk of reallocating water raises red flags in Yuma. Agriculture is a big part of the local economy. Drying up farms could dry up local businesses, too, from tractor dealers and seed companies to grocery stores and restaurants.

Farmers have the law on their side. But as times get tighter on the Colorado and the big urban areas hunt for water, farmers are concerned that could change.

“Congress could step in [and] perhaps the state legislature might have something to say also,” said Yuma citrus grower Mark Spencer.

Citrus grower Mark Spencer has faith that Western water law will protect him -- to a point. (Steve Baragona/VOA)

Even the pilot program makes people nervous, Weddle added. “Everyone’s certainly concerned, even if you do a small-scale program, if your water is going to come back. That’s a risk we’re taking. And that’s why this is a very short-term, small program.”

Farmers here are willing to do their part, Spencer said, but the fast-growing cities of central Arizona got themselves into this predicament.

“Maybe they’ve got to limit the number of houses that they can build, or the number of golf courses that they can put it, or the number of times that they can water their lawns,” he said.

But according to Phoenix water manager Kathryn Sorensen, the city has all the water it needs for the foreseeable future. The Colorado is a major water source for the metropolis, but not its only one.

“We’re not looking to ask Yuma to stop growing crops so we can grow houses,” she said. “Where we’re at is making sure we don’t run the system into the ground. And I think that there’s a collective risk for all of us in that.”

“We’re not looking to ask Yuma to stop growing crops so we can grow houses.” – Kathryn Sorensen, Phoenix water manager

Water will stop flowing out of Lake Mead if the level falls another 100 feet. That would be a disaster for Yuma’s farmers as well as for Phoenix, Sorensen added.

And Sorensen is aware of the risks fallowing poses to local economies. “Those things matter,” she said. “It needs to be done in a way that’s very sensitive to the community…and can provide some benefit to the local economy as well.”

To entice farmers to participate, the Central Arizona Project agreed to pay them $750 per acre per year to fallow their land. About 10 percent of the land on the Yuma mesa will be fallowed for the three-year program.

The commitment is small enough and short enough to satisfy the farmers. And it gives them a welcome opportunity to let their land rest. The Arizona desert sun bakes away germs that lurk in the soil. Crops planted after fallowing are more productive. But a fallow field generates no income. So getting paid for it is a bonus.

“It’s a sort-of symbiotic-type program here that’s a win-win for a lot of people,” Spencer said. He has 280 acres in the program. The money he earns is offsetting the costs of supporting young lemon trees elsewhere on his farm that are not yet producing fruit.

Weddle said farmers probably could have asked for more money, but, he added, “I feel the information right now is more important to get than to try to beat somebody up for how many dollars you can get.” Once they know how much water they can save, “then the marketplace will dictate the value of the water,” he added.

The marketplace already knows the water is valuable. A private company called Greenstone has bought land in Yuma and neighboring areas. Company executives declined to comment, but local farmers say Greenstone bought the land for the water rights. As the strain on the Colorado River increases, those rights may be more valuable than the land, and cities may be willing to pay good money for them.

Greenstone, a company specializing in water transfers, bought this parcel of land and others around Yuma. Locals say someday the water rights may be more valuable than the land. (Steve Baragona/VOA)

That is, if the company can sell them. The Yuma mesa’s irrigation district, not the landowners, owns the water rights. The district’s board of directors would have to approve a sale.

And that’s not likely, at least not today. Weddle and Spencer are both board members, and neither supports the idea.

“I’m certainly against water farms, other cities or towns or even absentee owners coming in and buying large parcels of property and trying to dry up 100 percent of that ground,” Weddle said.

But investors seem to be betting the situation will change.

Some kind of change is likely, Spencer says. Water probably will get more expensive. Growers probably will need more efficient — and more costly — irrigation systems. Alfalfa for animal feed is a major commodity here, but such a low-value crop may not make sense anymore.

“But one thing people have to realize,” Weddle said, “if they’re going to have milk, if they’re going to have steaks, they’re going to have to have alfalfa.” And, he added, it’s better to grow it on the marginal land of the Yuma mesa, rather than using up prime farmland elsewhere.

The Central Arizona Project’s Tom McCann counters, “Is it more valuable to have a pasture that an animal can wander around in or to have a vibrant city?”

Cities or farms? As water gets tighter, everyone who depends on the Colorado River will have to decide what is most valuable.

But there’s one silent stakeholder that’s been ignored for most of the last century. As humanity has tapped the river to the limit, there is a growing recognition of the devastation inflicted on natural ecosystems. And there are indications that attitudes are beginning to change.

Reviving the river

Outside San Luis Rio Colorado, Mexico, the namesake river runs completely dry. (Steve Baragona/VOA)

The Colorado River is conspicuously absent from the riverbed outside the city of San Luis Rio Colorado, just over the Mexican border from Yuma. A highway bridge carries traffic over a wide, barren strip of sand littered with beer bottles.

By the time the river reaches the Mexican town named for it, U.S. cities and farms have drained most of its water. The Morelos Dam 20 miles upstream shunts most of what’s left into a canal for Mexican cities and farms to drink.

And with groundwater pumping on both sides of the border, further drawing down the water table, the highway bridge outside San Luis Rio Colorado spans one of the driest spots on the struggling river.

It’s got another 70 miles to go before it reaches the Gulf of California. Most years, it never gets there. The river delta used to be a 2 million-acre wetland. Now, much of it has been reduced to a salt-encrusted wasteland.

But something changed last March. The gates of the Morelos Dam opened, and for the first time this century the river met the gulf.

Osvel Hinojosa, of the Mexican environmental group Pronatura Noroeste, inspects new growth at a restored site in the Colorado River delta region. (Steve Baragona/VOA)

A historic agreement between the United States and Mexico sent a six-week pulse of water down the river for one purpose: to aid the long, hard struggle to restore the ruined ecosystem.

“It’s really been a bit of a dream come true,” said University of Arizona biologist Karl Flessa who heads the program monitoring the ecosystem’s response to the pulse. “It’s something a lot of scientists hoped for for many, many years. And then to actually see it happen is really something quite extraordinary.”

The water brought residents of San Luis Rio Colorado down to the riverbanks to see the long-lost river return. Children who had seen only sand under the highway bridge splashed in the water.

A few months later, the river is dry again. But the pulse of water has left its mark.

The pulse was timed to give the seeds of native cottonwood and willow trees along the riverbanks the best chance to germinate and take root. Grow these trees, ecologists say, and the rest of the ecosystem will come, from bugs to bobcats.

The pulse flow flooded around 120 acres at a site known as Laguna Grande, about 30 miles downstream of San Luis Rio Colorado. Just a few months later, a fringe of green seedlings up to 3 feet high lines the riversides.

Spring floods were once a regular feature of this desert landscape. Given a chance, the ecosystem springs back to life.

Francisco Zamora at the Sonoran Institute, a US environmental group, stands on the banks of a stream flooded by the pulse flow. Newly sprouted trees line the water’s edge. (Steve Baragona/VOA)

“That’s the importance of the pulse flow. We can get new habitat very quickly,” said Francisco Zamora, who leads delta restoration work at the Sonoran Institute, a U.S.-based environmental group.

“And now we’re seeing some real biological results,” Flessa said. Satellite images show the delta is 23 percent greener than it was before the pulse. Not only is there new growth, Flessa said, but the existing plants are healthier.

These improvements happened much quicker than the painstaking efforts to restore Laguna Grande and other sites by hand. The Sonoran Institute and the Mexican environmental group Pronatura Noroeste have hired local workers to clear away invasive tamarisk trees, plant and tend new trees and install irrigation systems. Workers have brought about 180 acres of young forest back to life since the groups acquired this land in 2008.

“It could be done faster, with machines,” said Osvel Hinojosa, head of the wetlands program at Pronatura Noroeste. “But by involving people, we’re providing jobs in restoration” and giving workers a stake in the project’s success. “They see it as part of the community. They become supporters.”

Soaked in sweat from clearing irrigation channels, David Alfaro Rodriguez said Laguna Grande was a trash dump when he began working here. It was dangerous. Thieves brought stolen cars here to dismantle them.

David Alfaro Rodriguez works for the Sonoran Institute helping the restoration project at Laguna Grande. (Steve Baragona/VOA)

“There was nothing to see here before. You would only come here to find problems,” Rodriguez said.

It’s a forest now, the largest and densest stretch of cottonwood-willow forest on the Mexican side of the Colorado, according to the Sonoran Institute.

The jobs and the natural habitat have been a welcome addition to the community, Rodriguez added. “I come here in the afternoons with my family to spend time in the shade.”

The rebounding nature is attracting other locals, too. Native insects have found the cottonwood and willow trees. And migratory birds have found the insects. Camera traps have even caught bobcats with cubs wandering through the newly restored forest.

The Sonoran Institute’s short-term goal is to restore 2,300 acres by 2017. It’s still a fraction of the original habitat, but “that’s the beginning,” Zamora said. For the longer term, the group aims for 160,000 acres in the next two decades.

The environmental groups have set up a fund to sustain their restoration work with water they buy on the local market. With the Colorado basin in the midst of a historic drought, there’s no current plan to send another pulse downriver.

The pulse was part of a larger U.S.-Mexico agreement that expires in 2017, and negotiators will be back at the table soon working on a new one. Environmental groups are optimistic. They say that after spending the better part of the last century draining the river for their own benefit, people are starting to see value in Mother Nature.

“Things are changing in how we perceive the Colorado River,” Hinojosa said. “We citizens of the Colorado River are coming to understand that the river is a user of the water,” not just a source, “and we need to dedicate water for the environment.”

Cities, farms and the environment — the challenge for the coming century will be how to share a shrinking river.

Calls to action for saving the river

Las Vegas reuses nearly all of its wastewater. Water from homes and businesses is treated and released into the Las Vegas Wash wetland, from where it flows back into Lake Mead. (Steve Baragona/VOA)

It’s shaping up to be a difficult and dry century for the tens of millions of people who depend on the Colorado River. But all is not lost.

“They’re of course not doomed,” said the Rand Corp.’s Debra Knopman. “But they do have to act. And many of these actions are going to take years.”

Farms, cities and industries can all use water more efficiently than they do now, according to a report Knopman co-authored. Wastewater can be reused more aggressively. Desalination of seawater or salty groundwater is an option. The report even considered transferring water from as far away as the Mississippi River.

But these options will take a long time to enact and cost a lot of money, on the order of $2 billion to $7 billion per year.

RAND Corp. researcher Debra Knopman offered solutions to help repair the river. (Steve Baragona/VOA)

On top of the cost, it will take political will and cooperation among all the river users in the seven states and Mexico. The region’s long history of bitter feuds and protracted court battles calls for a degree of skepticism.

Tensions over water are a growing concern worldwide. The World Economic Forum’s “Global Risks 2015″ report ranks water crises as the eighth most likely risk to occur in the next decade, behind failure to adapt to climate change but ahead of data fraud or theft. They top the list in terms of impact.

But researchers note that water issues have historically spawned more cooperation than conflict.

Israel and Jordan negotiated over the Jordan River even while they were technically at war. Cambodia, Laos, Thailand and Vietnam shared information on the Mekong River throughout the Vietnam War. And Indus River cooperation survived two wars between India and Pakistan.

Pat Mulroy, who’d led the Southern Nevada Water Authority, says cooperation is better than ever among the seven states that share the Colorado River. They reached an agreement in 2007 that determines, in times of water shortage, who takes cuts, how much and when.

“They have stared reality ice-cold in the face,” Mulroy said of the states. They acknowledged that, “no matter what the grousing is behind the scenes we know that failure is not an option and we don’t have the time to pursue litigation. We had better get our act together.’”

Whether such actions will be enough to keep Lake Mead from dropping to deadpool will be the question of the century for the U.S. Southwest.

Bobbing on Lake Mead in his boat under the late morning sun, Mat Baroudi, the Las Vegas landscaper, said, “I just don’t want to see this jewel that we have out here dry up.”

“You’d hate to think something like that is going to happen here. I can’t imagine that the powers that be will let that happen,” he added. “But we’ll see.”

The future of tens of millions of people, millions of acres of farms and vast swaths of natural environment in the desert Southwest all hang in the balance.

Meet the people and the terrain of the desert Southwest in the five-part video series that inspired this report.

About the author

About the author

Steve Baragona is an award-winning multimedia journalist covering science, environment and health.

He spent eight years in molecular biology and infectious disease research before deciding that writing about science was more fun than doing it. He graduated from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill with a master’s degree in journalism in 2002.

Baragona co-wrote a documentary on the impacts of the 2012 drought in the U.S. Midwest that won four awards.

Credits

Reported, written, and produced by Steve Baragona

Photography and videography by Steve Baragona

Web Design by Stephen Mekosh and Dino Beslagic

Share and Comment

Share and Comment

Comments