The Making of the Constitution

On May 13, 1787 General George Washington arrived in the city of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Washington was the most famous man in the United States.

He had been the commander in chief of the army that overthrew the British in the Revolutionary War. The war made the 13 American colonies independent in 1783.

The colonies — now states — joined under an alliance of friendship, called a confederation.

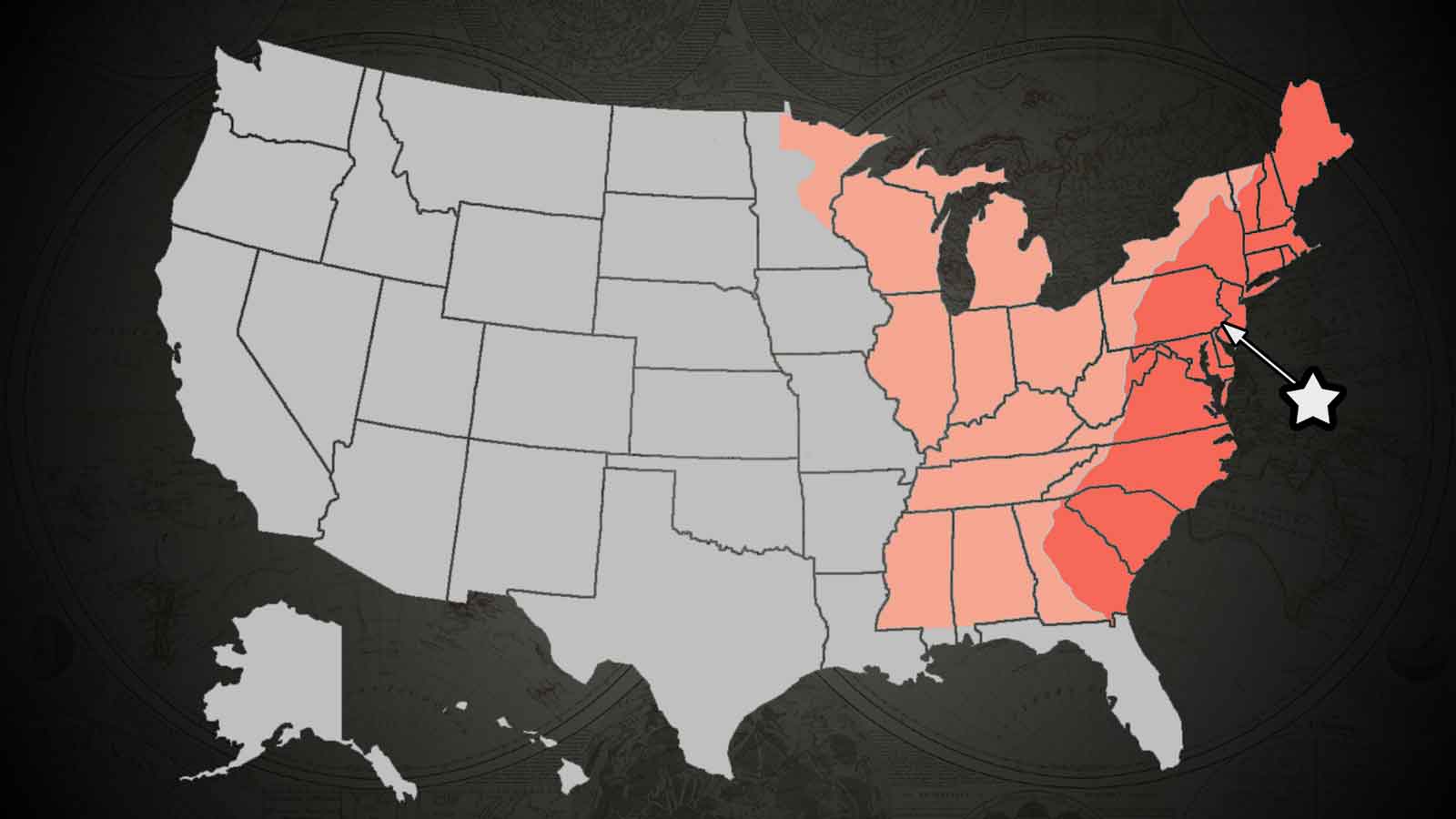

In 1787, the 13 states stretched along the Atlantic Ocean, from Georgia to present-day Maine. Philadelphia was the largest city. The U.S. also had rights to territory up to the Mississippi River. Spain controlled most of the rest of the area.

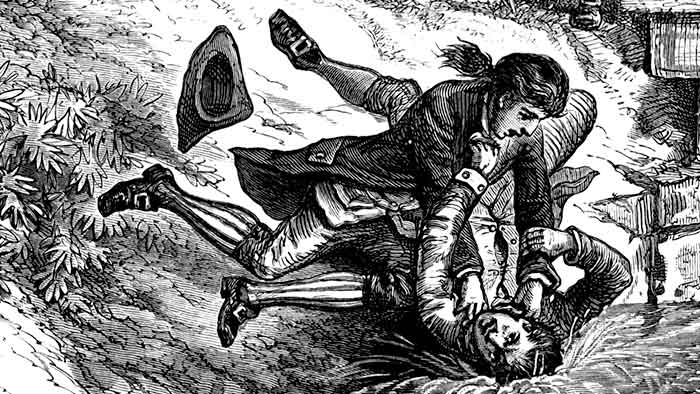

Beginning in the summer of 1786, some unpaid soldiers who could not pay their debts tried to prevent the courts from taking their farms. Shays' Rebellion was named after Daniel Shays, a former captain in the army. (University of South Florida)

But by 1787, the confederation was in trouble. Its Congress was weak. It could not solve disputes among the states. It could not pay its debts to other countries. It could not even pay the American soldiers who fought in the war for independence. And some of those unpaid soldiers were beginning to protest.

The protests frightened many people in power. The confederation government, they said, could not protect private property and prevent anarchy. They asked Congress to call a meeting of state leaders to discuss changes.

What problems led to a call to revise the Articles of Confederation?

“What a triumph for our enemies…to find that we are incapable of governing ourselves…!”

George Washington

Delegate from Virginia

George Washington was one of the people who believed a stronger government was necessary. Although he wanted to stay home after the war and take care of his estate, he agreed to attend a meeting to improve the government. In the late spring of 1787, horses and a carriage took him over 250 kilometers of rough road to join other state leaders in Philadelphia.

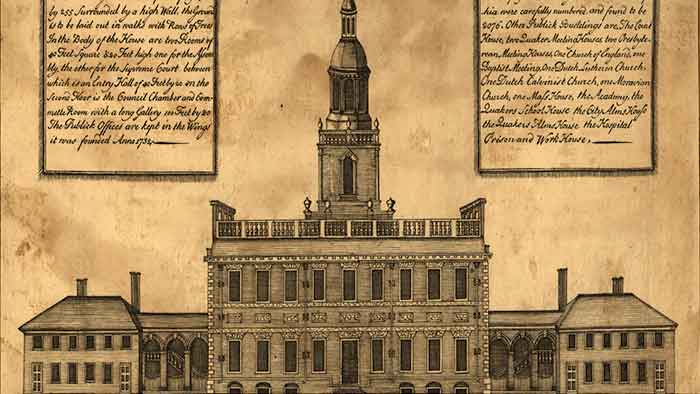

At the time, the meeting was called the Philadelphia Convention, or sometimes the Federal Convention or Grand Convention. Today we usually call it the Constitutional Convention.

The Philadelphia State House was one of the most important buildings in the early United States. Americans adopted the Declaration of Independence and created the Constitution here. (U.S. Library of Congress)

Eventually, 55 men from 12 states took part. Only the smallest state, Rhode Island, chose not to send someone.

The men who attended the convention were called delegates or deputies.

Portrait of the delegates

Age: The youngest was 26; the oldest 81. The average age was 42.

Education: Most had a college education. Several had graduate degrees. Almost half studied at Harvard, Yale or Princeton.

Professions: Law, business, finance, real estate and agriculture. Some were also governors, judges, doctors and military veterans.

Public service: Eight signed the Declaration of Independence; six signed the Articles of Confederation; and forty represented their states in the Confederation Congress.

The delegates elected George Washington president of the convention. But Washington said little during the meetings. It was another man from Virginia, James Madison, who quickly became a leader. Madison had come to Philadelphia with a plan to strengthen the power of a central government.

“… there can be no doubt but that the result will … have a powerful effect on our destiny.”

James Madison

Delegate from Virginia

James Madison was very intelligent. He was also very wise about politics. So he gave his plan to a more powerful delegate to read.

On the first day of the convention, the governor of Virginia, Edmund Randolph, described Madison’s plan for a national government. It had three parts, or branches.

- The first branch was a legislature that made the law. States with larger populations would have more votes than states with smaller populations.

- The second branch was the executive, or president. The president would enforce the law.

- The third branch was a court system, including a supreme court. The courts would rule on disputes about the meaning of the law.

Many of the delegates were shocked. Madison’s proposal was very different than the confederation government. The confederation government did not have a president or courts. And in the Confederation Congress, each state had one vote. The states were all equal. In contrast, Madison wanted to give more populous states more power than less populous states.

Over the next weeks, delegates stood and described their concerns about Madison’s plan.

“I would rather submit to a monarch, to a despot, than to such a fate.”

William Paterson

Delegate from New Jersey

William Paterson, a delegate from New Jersey, proposed a solution that gave the small states more power. The delegates voted on the New Jersey Plan. But they did not agree on it, either.

What were some points on which the delegates to the Philadelphia Convention disagreed?

The convention continued. The delegates met five — and sometimes six — days a week in the Assembly Room of the State House. It was small and hot. The men crowded around shared tables. Many took notes on paper with quill pens dipped in ink. They took their glasses on and off. They tapped their canes on the floor.

Independence Hall, Philadelphia

Early on, the delegates decided not to tell anyone else about their discussion. They decided to keep it secret so they could change their minds later. As a result, they kept the windows in the Assembly Room closed. The summer air hung still and heavy.

Around 3 o’clock in the afternoon, the delegates adjourned, or stopped, the day’s meeting. They walked a few kilometers to the places where they were staying. Some rented a room in a house. Others stayed in a tavern, a kind of hotel that also had a restaurant and bar.

City Tavern Restaurant, Philadelphia

Sometimes delegates met for dinner and continued their discussions informally. But the work of the convention was slow. And the men missed their wives, families and businesses at home.

Many were not sure the convention would succeed.

Three main issues divided the delegates.

How many representatives would each state have in Congress?

James Madison suggested representation should be based on population. For example, every 40,000 people might have one representative.

But delegates from small states fought against the idea. They did not want to be overpowered in Congress. They said each state should have the same number of representatives.

Roger Sherman from Connecticut partly settled the issue. He proposed a Congress with two parts: one part with representation based on population, and one part with equal representation.

But the Connecticut Compromise, as it was called, raised another question.

“Religion and humanity had nothing to do with the question [of slavery]. Interest alone is the governing principle with nations.”

John Rutledge

Delegate from South Carolina

How would the Constitution deal with slavery?

At the time of the convention, about one in five people living in the U.S. was a slave.

Slavery was legal in most states, and the economy of the whole country depended in part on the slave trade or slave labor. However, the majority of slaves lived in the South. Most worked on large farms called plantations that grew crops for profit.

The proportion of enslaved to free people increased from the state of Maryland southward. (1790 Federal Census Report)

Southern delegates wanted to include slaves in their population count. After all, the bigger the population, the more representatives in Congress.

But anti-slavery delegates objected. They pointed out that state laws treated slaves as property. Counting slaves in the population, they said, would just give slaveholding states more power to keep people enslaved. As the number of slaves increased, so would slaveholding states’ political influence.

Finally, the delegates returned to a formula from the confederation government. It said the government could partly count slaves when deciding how much to tax each state.

The delegates adopted the same formula. They decided to count “the whole number of free persons” and 3/5 of “all other persons” for the purposes of taxes and representation. The decision to count 60% of the slave population is known as the 3/5 clause.

What were some reasons for the 3/5 clause?

In addition to the 3/5 clause, the delegates created some other rules about slavery. They said the national government could not bar the states from taking part in the international slave trade until 1808 – over 20 years in the future.

They also said the national government would help stop rebellions in the states, including slave revolts.

And, they said officials in every state must return escaped slaves to their owners — even if the slave escaped to a state that banned slavery.

“South Carolina can never receive the plan if it prohibits the slave trade.”

Charles Pinckney

Delegate from South Carolina

What About a Bill of Rights?

The Philadelphia Convention was reaching an end. Some delegates had already left. It was September. The weather was turning cooler.

Much of the work was done. The delegates had decided to keep many elements of Madison’s plan for a central government. At the same time, they found ways to share power with the state governments. In this way, the Constitution created a system that was, as Madison later described it, “part federal, part national.”

Most importantly, the delegates agreed that the government’s power did not come from Congress, or a president, or a king, or even a divinity. They clearly stated that the people themselves gave the Constitution its power.

However, the Constitution did not create a democracy.

For most of the delegates, democracy meant a kind of anarchy. Scholars could point to only a few examples of successful democracies in history – and those were in small territories. In contrast, the U.S. of 1787 stretched about 1.4 million kilometers and included nearly 4 million people.

Population of Philadelphia in 1790

At about 44,000 people, Philadelphia was the largest city in the U.S. at the time of the Constitutional Convention. The 1790 Census showed the variety of people who lived and worked there. They included female heads of household, who often supported themselves and their families as teachers, small hotel operators or shopkeepers. (The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia)

Most states permitted only white men who owned property to vote – that is, about 6% percent of the population. Women, slaves, free men of color and many poor men could not vote. Native American Indians could not vote, either, because they were considered to belong to separate nations.

Why was the new government not considered a democracy?

But most delegates believed everyone had rights the government could not give or take away.

Many state constitutions said clearly what those rights were. In the final days of the Philadelphia Convention, another delegate from Virginia, George Mason, stood and proposed that the national constitution also describe the people’s rights – for example, the right to be judged in court by a jury of local citizens, or the right to follow a religion freely.

Some delegates agreed with George Mason. But others, including Madison, did not think a bill of rights was necessary. If the rights came naturally, opponents argued, they did not need to be described.

Besides, most delegates were tired. They were ready to go home to their families and their other work. They voted not to include a bill of rights.

George Mason was so angry he refused to sign the final document.

Two other delegates also refused to sign. Eldridge Gerry of Massachusetts objected especially to the lack of a bill of rights. Edmund Randolph, who had presented Madison’s plan, thought the Constitution gave too much power to the central government.

“I would rather chop off my right hand than put it to the Constitution as it now stands.”

George Mason

Delegate from Virginia

What kept some delegates from agreeing to sign the Constitution?

Some delegates still personally objected to parts of the Constitution. But they signed the document to show their states supported it. (“The Signing of the Constitution” by Louis S. Glanzman, 1987)

On September 17, 1787, the remaining delegates walked to the front of the Assembly Room and signed their names to the Constitution. An additional delegate who was not there asked someone else to sign for him. The final document includes 39 signatures, beginning with Washington’s.

“I agree to this Constitution with all its faults … because I think a general government necessary for us…”

Benjamin Franklin

Delegate from Pennsylvania

The Constitution had gone far beyond making a few changes to the confederation government. Instead, it created a new government that had the power to create a national economy and national organizations.

Yet the document was only a proposal. First, it had to go back to the Confederation Congress. Officials there asked each state to hold a convention to vote on the proposal. Nine out of the thirteen state conventions had to ratify, or approve, the Constitution in order for it to become legal.

Over the next two days, printers in Philadelphia made a copy of the document and hurried it to newspapers across the country.

“Yet these are the men who tell us… that we are incapable of enjoying our liberties — and that we must have a master.”

Mercy Otis Warren

Critic of the Constitution

For the first time, the public learned what the men in Philadelphia had been doing. Many people were angry. They did not want another strong, central government that ruled them from a distance. Ending that system, they said, was why they had fought a war with Britain!

Others demanded a bill of rights. After all, they had one in their state constitutions.

Others did not want a president. How would he be different, they said, than a king?

For nine months, Americans discussed and debated the proposed Constitution. Even though not every person could vote, most were able to talk about what kind of government they wanted. Some scholars say the ratification debate over the U.S. Constitution was the most democratic act in the history of the world up until that point.

Delaware license plates show the state is proud to be the first to approve the Constitution. (Flickr)

The state of Delaware ratified the Constitution almost immediately.

Five other states followed. But several of the big states – including Virginia and New York – raised serious objections. They did not want to reject the Constitution and leave the union of states; however, they did not want to agree to the Constitution without a bill of rights.

State conventions suggested hundreds of amendments to the Constitution. James Madison reduced them to 19. Congress approved 12. In 1791, the states ratified 10. (Center for Constitutional Rights)

In Virginia, James Madison stepped forward again. He promised the state convention that a new Congress could make additions to the Constitution. Those additions could describe the people’s rights and limit the power of the government. Other states also agreed to trust the new Congress to add a bill of rights.

A little more than a year after the delegates met in Philadelphia, the first nine states agreed to ratify the delegates’ proposal. On March 4, 1789, the U.S. Constitution went into effect as the supreme law of the land.

How did the first Congress resolve the main problem many saw in the Constitution?

The following year, voters unanimously elected George Washington the country’s first president. He again left his estate in Virginia and made the weeklong journey to New York, the country’s first official capital. His wife, Martha, later joined him.

Now Washington’s job was to put the Constitution into practice. He knew the task would not be easy. The Constitution did not answer every question about how the government operated, and it did not settle every argument the delegates or the public raised.

In fact, Americans have continued to debate the Constitution throughout the country’s history. But the Constitution has remained our highest form of law. It is the oldest, written national constitution still used today.

What is unique about the U.S. Constitution?

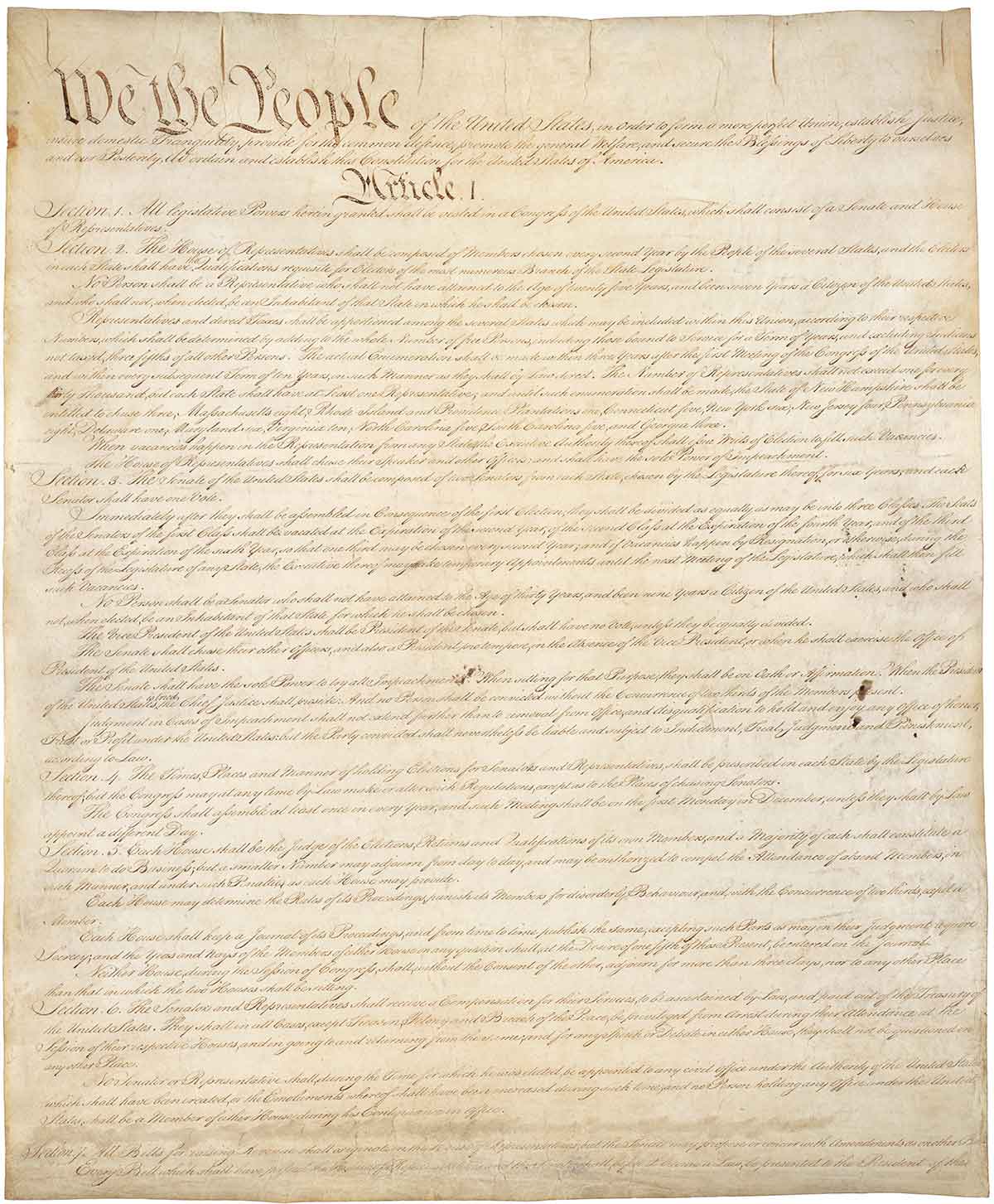

The signed Constitution is on display at the National Archives in Washington, DC. It is four pages long and about 5,000 words. (U.S. National Archives and Records Administration)

Some scholars say the secret of its success is its amendment process, which has allowed the Constitution to be changed peacefully. Since 1788, amendments to the Constitution have expanded the right to vote to almost all U.S. adult citizens.

Others say its strength is in the division of power among three branches of government. Washington himself wrote that the Constitution gave the central government enough power to be effective, but not too much to be oppressive. And, he said, he was amazed that people with so many different interests could agree on a system of government. Their ability to find unity, he wrote, was “little short of a miracle.”

Lesson Plans for Teachers

About the Series

The Making of the Constitution is part of the VOA Learning English series “The Making of a Nation.” The series teaches U.S. history by telling the stories of major events and characters from the country’s founding to the present day.

Credits

Lead writer and editor: Kelly Jean Kelly

Visual producer: Roger Hsu

Education specialist: Dr. Jill Robbins

Web designers: Stephen Mekosh and Dino Beslagic

Consulting scholar: Linda R. Monk, J.D.

With additional thanks to the National Constitution Center, Independence National Historical Park and City Tavern Restaurant

Comments