Atonement on the Tigris

A Century Later, Armenians, Kurds and Turks Move Forward From a Tormented Past

BY MIKE ECKEL

“I wasn’t a good Muslim and I’m not a good Christian either. But I am a good Armenian.”

DIYARBAKIR, Turkey — Most of the congregants at Easter Mass at the rebuilt Church of Saints Cyriacus and Julietta in this Turkish city on the banks of the Tigris were not Christian.

They were Muslim.

Among the handful of Christians was Gafur Turkay.

Five years ago, he turned away from the religion he was raised in — Islam — and openly embraced the religion of his ancestors, a choice that he said was less about being Christian and than it was about being Armenian.

Priests are flown in from Istanbul for major religious holidays like Easter since there aren't enough worshipers in Diyarbakir. Armenians in Istanbul and elsewhere hope the revival of Sourp Giragos may encourage more 'hidden Armenians' to come forward and embrace their ancestry. (VOA/Mike Eckel)

It was also, he said, about honoring his grandfather, whose throat was cut in the violence that in 1915 all but wiped Armenians from the map in this and other parts of the dying Ottoman Empire.

“For my grandfather, for the massacres, for the Armenians, I did it for them,” said Turkay, whose family was forced to adopt that surname. “I wasn’t a good Muslim and I’m not a good Christian either. But I am a good Armenian.”

Hundreds of thousands died — many historians say more than 1 million — in an event that many scholars, and Armenians worldwide, regard as the 20th century’s first genocide.

For Turks, to describe what began on April 24, 1915, as genocide is inaccurate and demeaning. The Turkish government today says indeed there were mass killings of Armenians and other Christians, but they weren’t ordered by the government and they happened in the course of a brutal war, in which Turks were also victims.

Cemalettin Hasimi, head of the Directorate General of Press and Information in the Office of the Prime Minister of the Republic of Turkey.

One hundred years after those events, which bitterly divide Armenians and Turks to this day, Turkay’s personal struggle is a coming to grips with his ancestry — and a symbol of a slowly emerging reconciliation.

That reconciliation has meant being able to speak openly about his decision, and to worship in the rebuilt Armenian Apostolic church, known around Diyarbakir by its Armenian name, Sourp Giragos.

At the heart of this slow thaw are the Kurds, the ethnic group that dominates in Diyarbakir and this part of Turkey, a group that has also struggled to assert its own identity. Kurds acknowledge some of their forefathers participated in the killings of Armenians, but insist it was on behalf of the government, and point out that other Kurds also helped rescue Armenians.

“Fifty years ago, it was an honor for a Kurd to say ‘I killed a lot of Armenians, I am a hero,’” said Turkay, 49, who runs a busy insurance brokerage in Diyarbakir. “Now, they say ‘we are sorry. We killed your grandfather.’”

These are the politics of identity that have been tangled into this small corner of the turbulent Middle East for a century. It’s a narrative that says Turks kill Armenians; Kurds kill Armenians; Turks kill Kurds; Kurds kill Turks.

But the politics are being slowly untangled. These days, Kurds atone before Armenians. Turkey expresses condolences. Armenians begin to emerge from lives hidden for generations.

Reliving the Past

The streets in Diyarbakir’s old city, where Sourp Giragos is located, are a maze of cobblestone alleys, where wet laundry drips in the mornings, children play ball against the walls and the tinkling sound of spoons stirring glass tea cups spills out of cafes.

What began 100 years ago Friday was unremarkable for a region that had been racked by spasms of sectarian violence for centuries. What was remarkable was the scope, intensity and organization of the slaughter — the dying breaths of a 700-year-old empire and the birthing pains of a new country.

In the 19th century, in much of Ottoman Anatolia, Armenians co-existed with a mash of ethnicities and religions, as they had for centuries before. In pockets around the region, Kurds lived alongside Turks; Greeks alongside Assyrians, Jews and Christians near Yazidi and Chaldeans.

Armenian refugees arriving at an unknown location after leaving Ottoman Turkey c. 1920. (Courtesy the Near East Relief Historical Society, Near East Foundation collection, Rockefeller Archive Center)

Many Kurds in Diyarbakir, a city 900 miles southeast of Istanbul, say that Armenians stood apart because of their numbers, their social prominence, their renown as artisans and craftsmen, and their religion. For Kurds, “Armenian” was synonymous with fine ironwork, making doors, fences and similar goods.

Competing for influence in the region in the late 1800s was Christian Russia. Armenians were seen as a danger, seeking to cleave off territory from a fragile empire. A group called the Armenian Revolutionary Federation led political resistance against the Ottomans, and tried to assassinate one of the last sultans.

Pogroms in Diyarbakir in 1895 ransacked many Armenian shops and homes. Various estimates put the death toll in the thousands.

By 1908, progressive reformers in Istanbul known as the Young Turks had amassed power from an ossified Ottoman leadership.

With the outbreak of World War I in 1914, and Russia threatening, the Ottoman Christian populations were seen as a national threat. More than 200 Armenian intellectuals were rounded up in Istanbul beginning on April 24, 1915, imprisoned and later executed.

Etyen Mahcupyan, a former senior advisor to Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu and also an ethnic Armenian.

Over the following months and years, much of the Armenian population, along with Assyrian Christians and others, was marched to Lebanon through the Syrian desert where many died. Others were summarily executed. The more fortunate fled from Lebanon to Europe and America, in many cases destitute.

Historians — Armenian, Western and some Turkish — put the death toll at more than 1 million. The Armenians call it medz yeghern, or “great crime.” The Kurds call it fermana fileyan, “deportation of the Armenians.” The Turks call it 1915 оlaylari, “the events of 1915.”

In Diyarbakir and much of eastern Turkey, some Kurdish tribes under the name of Hamidiye Brigades, a government-backed militia established earlier, took the lead in the killings. Many were told that if the Armenians remained, Russia would seize the lands and expel the Kurds.

With the revival of Sourp Giragos, Armenians, and some Kurds, are hoping for a revival of region's multi-ethnic character. Ergun Ayik, who heads the foundation that restored Sourp Giragos, is hoping someday to restore a church with similar architecture called Sourp Cirkis, located in another part of Diyarbakir. (VOA/Mike Eckel)

The Kurds “were idiots and they believed them and by this, the Kurds and the Armenians became enemies and this was the goal of the Turkish state and they succeeded,” said Ahmet Pamukcu, 95, who said his grandfather held the religious title of “sheik.”

Some Kurdish families and tribes, like Pamukcu’s, sheltered fleeing Armenian families or helped them escape.

“And then (the Kurds) were remorseful,” he said. “In the end, they were so sorry for this but everything was finished.”

Ottoman rule gave way to the Turkish Republic in 1923 and nationalists turned their sights on Kurds, part of a policy known as “Turkification.”

A rebellion in Diyarbakir in 1925 resulted in thousands of Kurds being killed. That, and other uprisings in the following decades, gave birth to an idiom used to this day in Kurdish regions, according to Abdullah Demirbas, a Kurd who is the former mayor of Diyarbakir’s old city and who actively backed the restoration of Sourp Giragos.

“For breakfast, they (the Turks) had the Armenians,” Demirbas said. “Then for lunch, they had the Kurds.”

Remains of History

Sourp Giragos re-opened for worship in 2011 after a $2.5 million renovation. But there is no real community of Armenians or church-goers yet, so priests must fly in from Istanbul to conduct services at major holidays like Easter.

Relics of old Armenian communities dot the countryside outside of Diyarbakir.

One hamlet to the east is known in Kurdish as Derkhist, which translates as “Toppled Church.” An Armenian church once stood on a grassy hilltop overlooking a dusty road and farms scattered into the distance. Some gravestones still stand upright, most are broken and toppled. Some Armenian writing is visible on others.

In the village of Derkhist, about a two-hour drive east of Diyarbakir, headstones from an graveyard are all that remains of an hilltop Armenian church that Kurdish villagers said was demolished some 90 years ago. (VOA/Mike Eckel)

A local farmer said that, decades ago, Kurdish villagers used the stones from the church to build homes for themselves.

Sourp Giragos, in the section of Diyarbakir sometimes known as the Citadel, itself has been reincarnated over the centuries.

Burned to the ground, then rebuilt in 1880, its bell tower was destroyed by lightning in 1913. A Gothic tower with a clock that was built in its place was destroyed by cannon fire in May 1915 after it was deemed inappropriate for a Christian church to have a tower taller than the city’s minarets.

“For breakfast, they had the Armenians. Then for lunch, they had the Kurds.”

In the early 1990s, its wooden roof collapsed under the weight of snow.

Today, the streets surrounding Sourp Giragos are as they have been for decades: a maze of cobblestone alleys, where wet laundry drips in the mornings, children play ball against the walls and the tinkling sound of spoons stirring glass tea cups spills out of cafes.

Every other brick or concrete wall is tagged with Kurdish graffiti praising the guerrilla fighters of the banned Kurdistan Workers’ Party, known as the PKK, and another Kurdish military unit known as the YPG.

With the help of U.S. lawyers like Mark Geragos, descendents of Armenians killed during the violence that began in 1915 have won legal judgments against life insurers for claims taken out by their forefathers.

In the 1980s and 1990s, a push for greater autonomy by Kurdish nationalists prompted a harsh crackdown by the state. Turkish security forces attacked the PKK, pushing many Kurds to seek safety in the mountains. Others fled to Diyarbakir, swelling the city’s population. Few Turks remain today.

Between 1984 and 1999, when the PKK’s founder was captured and imprisoned, thousands died on both sides; more than 30,000, according to one count, by the International Crisis Group. A second phase of the insurgency erupted after 2004; Diyarbakir saw sporadic violence as recently as 2006.

Diyarbakir is largely a Kurdish city, and support for Kurdish separatists runs strong among the population. The insurgency waged by the Kurdistan Workers' Party, or PKK, is for the moment largely dormant. Many Kurdish fighters have also been drawn into the fight against Islamic State militants, just across the border in Syria. (VOA/Mike Eckel)

Today, Kurdish fighting is largely dormant, eclipsed by the crises in Iraq and Syria and efforts by some Kurdish leaders to negotiate directly with the Ankara government.

This in itself is a sea change from a generation ago, when “Kurdish” as an ethnicity wasn’t even recognized by the government. They were known instead as “Mountain Turks” and for years, it was expected they would be “Turkified”— assimilated into Turkish society.

Instead, the Kurds, who are Muslim and who make up around 20 percent of Turkey’s overall population, have carved out a growing economy and some autonomy. It’s an echo of the Armenian push for autonomy before 1915, said Ohannes Kilicdagi, a sociology instructor and Ottoman Armenian expert at Bilgi University in Istanbul.

“I don’t know whether Kurdish people or Kurdish political activists are well aware of this, but I think this is also a factor making the Kurdish people have empathy for the Armenians of that time,” Kilicdagi said.

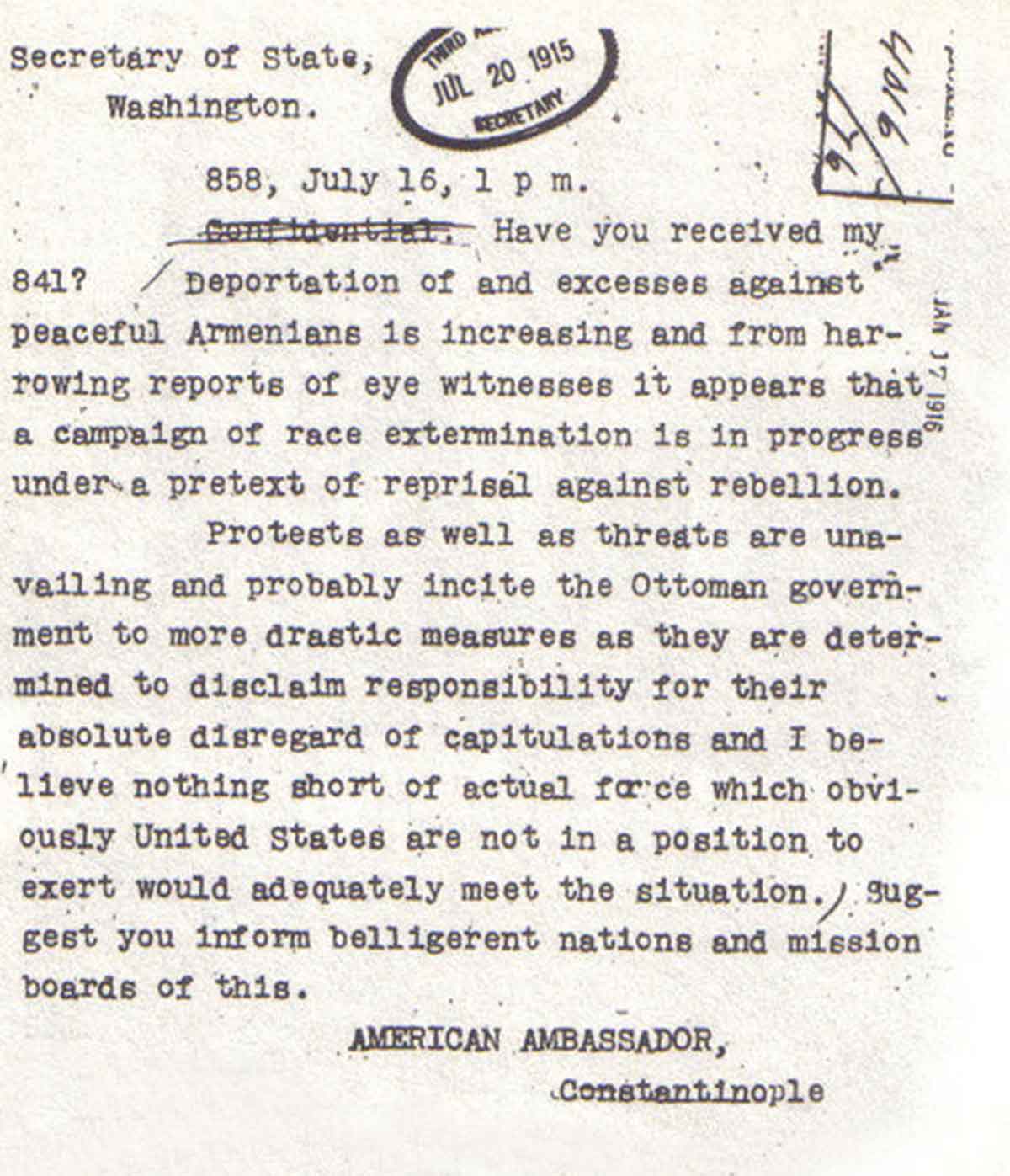

An official telegram sent by Henry Morgenthau Sr., then the U.S. ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, on July 16, 1915, in which he describes what was happening to Armenians as 'race extermination.' (Creative Commons)

Unquestionably, Turkish society has seen seismic shifts in the past 20 years. People can openly discuss, in newspapers, on TV, in public spaces, whether the 1915 events were in fact genocide; earlier, you could be thrown in jail for raising the issue. State-run media now broadcast programming in Kurdish.

Last year, in an unprecedented statement, then-Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan publicly offered condolences to Armenians for the 1915 events, calling them “inhumane.”

This month, Pope Francis argued that the killings be recognized as genocide, a statement that angered the Turkish government. A day later, United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon labeled the killings “atrocity crimes,” not genocide.

The United States has stopped short of using the word genocide.

“The president and other senior administration officials have repeatedly acknowledged as historical fact and more in the fact that 1.5 million Armenians were massacred or marched to their deaths in the final days of the Ottoman Empire,” U.S. State Department spokeswoman Marie Harf said.

Kurds and Armenians alike say shifts in Turkish society are due in part to the Kurdish struggle, which has made room for discussion of Turkey’s 20th century history.

“The Kurdish struggle has made Turkey more democratic,” said Turkay, the Diyarbakir Armenian. “It has helped us, Armenians. We can easily speak about our identity now.”

Discussion Is Not Recognition

Ergun Ayik, who heads the foundation that oversaw the process, said many parishioners in attendance at holidays like Easter were “hidden Armenians”– Armenians whose forefathers survived the violence 100 years ago by converting to Islam or assuming new identities.

Many Armenians say until Ankara says “yes, it was genocide,” any other gesture is empty. That goes particularly for those in the diaspora — found mainly in the United States, France and Russia — who outnumber Armenians living in modern Armenia and are vastly more wealthy.

One of the biggest stumbling blocks may be the question of reparations. Mark Geragos, a well-known Los Angeles defense lawyer, argued Turkey was liable for billions of dollars of damages and the return of Armenian properties seized beginning in 1915, similar to what happened for Jewish victims of Nazi Germany’s crimes.

“Tomorrow, Turkey can say tomorrow ‘we recognize the genocide.’ Snap snap. That doesn’t matter,” said Geragos, who has negotiated millions of dollars in life insurance claims from European insurers for descendants of Armenian victims.

Diyarbakir is one of the largest cities in southeastern Turkey, dominated primarily by Kurds, most of whom practice Sunni form of Islam. Diyarbakir's population swelled over the past century, as many Kurds were driven from villages into the city in the face of Turkish campaigns to suppress insurgency movements. (VOA/Mike Eckel)

“Where you need to get is reparations, restitution,” he said. “This was the first main, major, not just genocide, but mass atrocity crime of the 20th century and it has never been resolved from a restitution or victims’ standpoint.

Erdogan’s offer of condolences last year was significant, but it made no use of the word “genocide.” Cemalettin Hasimi, a top adviser to the current Turkish prime minister, Ahmet Davutoglu, said the killings of 1915 were a tragedy, depriving the country of its multicultural character.

But, he said, “historically, it is a factual mistake to call it a genocide.”

“We do not ignore the suffering on the ground, the suffering of the Armenian community, the suffering of Turkish identity. We do not want to ignore the different dimensions,” he said. “When you do that, when you insist on calling it (genocide) as a political obsession… you are not doing justice to the relationship, the complexity of the relationship between the Turkish community and the Armenians.”

That’s also reflected in public perceptions within Turkish society, said Cem Tuzun, a social activist in Istanbul: that the push to label the killings “genocide” is politically motivated.

“The term … is created by groups and countries which are trying to re-shape the Middle East and create division among ethnic and religious groups,” Tuzun said. “If there has been a genocide though, this has to be decided by historians after thorough research of historical facts. It should not be decided by politicians because they have their own agenda.”

The ultimate stumbling block for the Turkish Republic may be an existential one, said Akin Unver, a professor of international relations at Istanbul’s Kadir Has University.

“Turkey can’t call these acts a genocide without willingly shaking the very foundations of modern Turkey and the narrative of its founding fathers,” Unver said. “This is above all else a threat to state identity and state survival from an ideological point of view.”

Armenian Resurrection

Kurds, who make up around 20 percent of Turkey’s population, have struggled, often violently, for autonomy or even independence for decades. In recent years, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, banned in Turkey and labeled as a terrorist group by the United States and European Union, has shifted in recent years toward seeking a political solution to Kurds’ status within Turkey.

“When you insist on calling it (genocide)… you are not doing justice to the relationship, the complexity of the relationship between the Turkish community and the Armenians.”

The reconstruction of Sourp Giragos, once the largest Armenian church in the Middle East, began in 2009, pushed along by members of Istanbul’s Armenian community, with donations from around the world.

At Abdullah Demirbas’ behest, the city contributed around 20 percent of the $2.5 million renovation costs. In 2011, the church began holding services; the next year, it held its first Easter Mass in nearly 100 years.

This year, on Easter Sunday, about three weeks before the April 24 anniversary, Sourp Giragos was festive, filled with the chanted liturgy and thick clouds of incense. Pews held more than 100 worshipers, plus reporters and curious spectators.

Some congregants came from Istanbul, where an estimated 40,000 Armenians now live, some with Diyarbakir ancestry. Only a handful of attendees took communion from the priests, who were flown in from Istanbul, as they are for major holidays like Easter.

Sourp Giragos has gone through cycles of decay and rebirth. Its Gothic bell tower was destroyed in May 1915, according to the foundation's director, after authorities deemed it inappropriate that a Christian church's structure would rise higher than minarets of nearby mosques. (VOA/Mike Eckel)

In the early years of the Turkish Republic, Armenians who remained were often forced to convert to Islam and assume new names. Some married non-Armenians and raised their children as Muslim to protect themselves and their families. Like Turkay, they are now known colloquially as “hidden Armenians.”

Ergun Ayik, who heads the foundation that rebuilt the church, said 10 have been baptized at Sourp Giragos over the past two years.

In the years after 1915, many Armenians who escaped being killed or forced to leave ended up hiding their identities, changing their names, intermarrying with Turkish and Kurdish families, and converting to Islam. Some of the descendents of these 'hidden Armenians' are now beginning to come forward, to convert to Christianity, or talk more openly about their identities. (VOA/Mike Eckel)

There aren’t enough people to have regular services yet, but, Ayik predicted, more Armenians will emerge in the future, drawn to the church not so much for religion but as a symbol of an Armenian past.

For Armenians, “ethnicity is more important than religion. You can change your religion,” he said. “But you can’t change the blood in your veins.”

As Mass concluded, people streamed into the courtyard to eat traditional bread called choreg; to mingle, smoke cigarettes and drink tea in bright sunshine.

The church’s bell tolled from the tower that was built to the same height as it was before it was destroyed 100 years ago.

Then from the minarets just a stone’s throw away, the Muslim call to midday prayer began.

About the Author

About the Author

Mike Eckel is a reporter, editor, blogger and multimedia journalist who has worked in places around the world including Donetsk, Grozny, Phnom Penh, Moscow, Vladivostok, Washington and elsewhere. Prior to VOA, he worked for the Christian Science Monitor, spent more than a decade with The Associated Press and freelanced for many other publications.

Credits

A Production of the Turkish, Armenian, Kurdish and English Services of Voice of America

Written and Reported by Mike Eckel

Additional Reporting by Melek Caglar, Vivian Chakarian, Fakhria Jawhary, Serdar Keskin, Inesa Mkhitaryan, Hulya Polat, Arman Tarjimanyan

Production Assistance by Douglas Johnson, Jeff Swicord

Web Design and Development by Stephen Mekosh, Edin Beslagic

Comments