Adrift The Invisible African Diaspora

A group of 104 sub-Saharan Africans on board a rubber dinghy wait to be rescued 25 miles off the Libyan coast. (Reuters)

Reported by Abdulaziz Osman and Nicolas Pinault

Edited by Pete Cobus

February 2016

Introduction

As Europe continues to absorb a migrant flow of seemingly Biblical proportions, stories of those fleeing the shock of war in Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan have come to dominate headlines.

But stories of sub-Saharan Africans, the economic migrants and refugees of chronic instability and regional violence, are less likely to resonate globally — unless their travails are met with calamity.

Of an estimated 130,000 Africans who attempted the journey in 2015 alone, most are escaping the entrenched day-to-day norm of institutionalized and grinding poverty — what some call the residual effects of a bygone colonial era.

In a makeshift encampment in Rome, 16-year-old Gambian migrant Morro Saneh put it more succinctly: “We simply want to live like human beings.”

Hailing from even the farthest reaches of the Sahel, the sub-Saharan migrants’ two primary routes to the “promised land” intersect Libya, the lawless morass of internecine warfare and dueling government entities. It’s here, in the cauldron of the post-Arab Spring Maghreb, where the grim prophecy attributed to ousted despot Moammar Gadhafi appears to be coming true: “The Mediterranean will become a sea of chaos.”

Those open waters now before them, an oceanic expanse of desert behind, they’re faced with the defining decision of their journey: whether to risk crossing fickle tides that, having claimed a record 3,771 migrants in 2015, on a calm day reveal the tantalizingly close shores of Southern Italy. But even for those lucky enough to reach the resort-studded coast, paradise quickly becomes a kind of purgatory. Like their Middle Eastern counterparts, the sometimes stateless travelers remain deadlocked between smugglers who exploit their hardship with impunity, and the governments that won’t permit them to stay. These are their stories.

Editor’s note: Despite important distinctions between the terms migrant, refugee and asylum seeker, we were unable to confirm the entire personal backstory of each subject interviewed, and therefore use the terms somewhat interchangeably.

Part I: Routes

Part I: Routes The Road In

African migrants begin the hazardous journey from Niger to the coast of Libya. (Reuters)

According to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), some 90 percent of African migrants arrive in Europe via Libya; about 10 percent via Egypt. The West Africans — predominantly from Senegal, Gambia, Ghana, and Nigeria — arrive in Sabha, Libya via Mali and Niger before making their way to Tripoli, sometimes traveling thousands of miles in as few as two weeks, and sometimes taking years.

From the Horn of Africa, the predominantly Eritrean or Somali travelers arrive via Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda and the Sudans.

Cellphone video of Somali migrants crossing the Mediterranean on a trafficker vessel from Egypt. (Obtained by VOA/Abdulaziz Osman)

‘Travel through the Sahara is worse than travel through the sea. In the sea you either die or survive, but you will not be subject to torment and endless pain.’

– Hafsa, Somali female, in Rome

All routes converge in Libya, whose coast lies some 160 nautical miles off Lampedusa, largest of the Italian Pelagie Islands and the nearest strip of European soil.

Cellphone video of Somali migrants on a European Union vessel. (Obtained by VOA/Abdulaziz Osman)

Sub-Saharans represent less than 15 percent of Europe’s 2015 surge of displaced persons, the largest the continent has seen since World War II. Nearly all of them arrive via Italy. Unlike neighboring Greece, which saw a dramatic spike in migration triggered by wars in Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan, Italy’s influx of sub-Saharans remains fairly consistent with prior years.

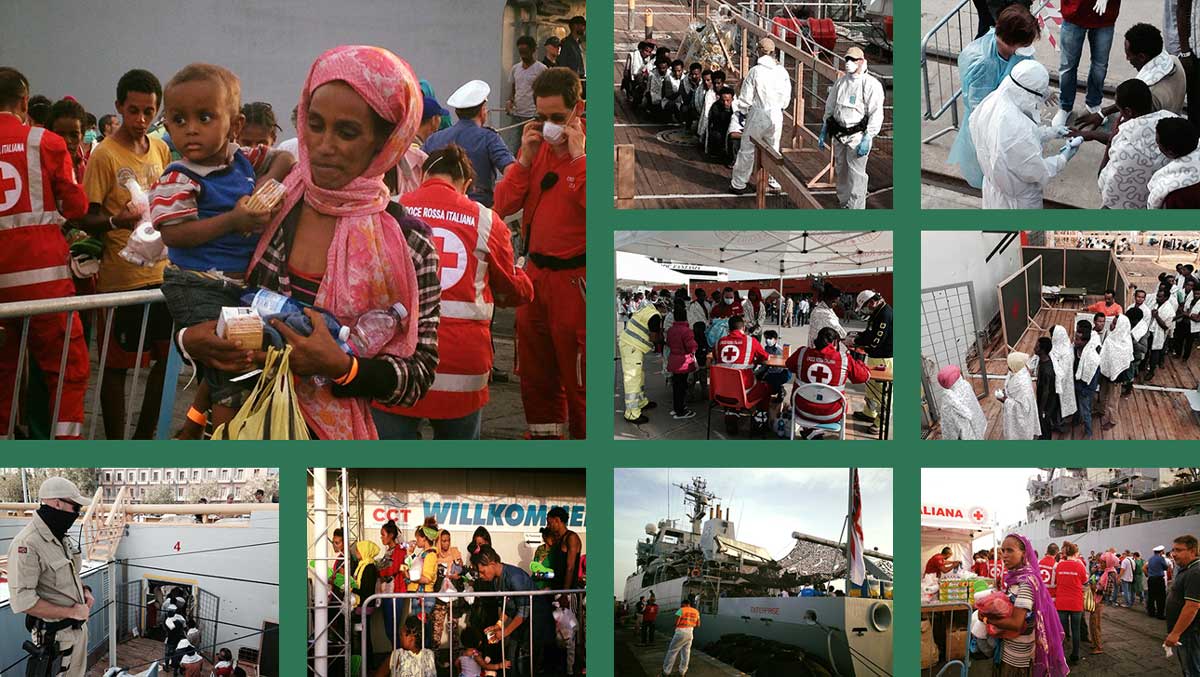

Click or Tap Image to Open Gallery

“There’s been no migrant ‘surge’ in Italy this year,” says Federico Soda, Rome-based director of IOM’s Coordination Office for the Mediterranean. “Cumulatively, the numbers are similar to 2014, but the ethnic and regional composition is different — that is, far fewer Syrians, who now take Balkan routes. It’s more West Africans, who are primarily economic migrants, and perhaps they are overlooked to a degree. Not so for those fleeing the hardship of instability and insecurity in the Horn.”

Interview with Federico Soda, Director of IOM's Coordination Office for the Mediterranean, Rome, Italy. (VOA/Nicolas Pinault)

Part II: Libya

Part II: Libya Edge of the Abyss: Descent Into Libya

Flip-flops abandoned by a migrant in the desert near the Libyan border. (Reuters)

For journeying migrants, Libya is a paradox. The primary destination of often-lethal Sahara treks, it’s also the principal jumping-off point for perilous Mediterranean crossings by dinghy. According to nearly all of the travelers we interviewed, it’s both the grimmest portion of the trip and the fulcrum on which their fortune pivots. A haven for criminal groups and terrorist organizations, the failed North African state — once a major employment hub for sub-Saharans —has become a gallery of horrors. A recent United Nations report exhaustively details accounts of torture, slavery, rape and extortion by armed vigilantes, smugglers and government officials who run vast Interior Ministry detention centers.

‘Libyans at the border beat us with plastic tubes, forcing us to push vehicles bogged down in sand … they paraded us under the scorching sun while eating and drinking in front of us.’

– Husein Muhidiin, Somali male, in Milan

Click or Tap Image to Open Gallery

Despite comprehensive documentation of rampant abuses, most migrants are unaware of the dangers, says IOM’s Soda: “They do not know that the smugglers are increasingly violent.”

As 23-year-old Malian Sama Tounkara describes it, “In Tripoli, every day we had to run.”

Rescued Nigerian woman stranded at Tripoli harbor, Libya. (AP)

Malian Migrant Sama Tounkara talks about a gunman in Libya. (VOA/Nicolas Pinault)

Part III: Testimonies

Part III: Testimonies The Crossing: Testimonies

Somali migrant Rahma Abukar Ali and her baby Sofia in Gelsenkirchen, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. (VOA/Abdulaziz-Osman)

A 33-year-old mother of seven who gave birth on the German naval frigate Schleswig-Holstein; a pair of 16-year-old Ethiopians imprisoned by smugglers until family members paid a ransom of $8,000 apiece; a Somali man who saw men drink their own urine as death crept near in the desert. Each has a unique story, but their conclusions depend on the fateful Mediterranean crossing.

Video Testimony: Rahma Abukar Ali, 33, Somalia: When Rahma Abukar Ali boarded a migrant ship in Libya on August 22, she knew the trip would mark the start of something new and hopeful or bring an end to her life.

Ali had spent the last five months of her pregnancy making her way from Somalia to the Libyan coast, trudging mile after mile through the searing Sahara Desert. Her only relief from walking: when she slept or crammed into trucks crowded with others fleeing the battle-scarred Horn of Africa.

“I was feeling dizzy; I was tired because of the long journey,” she says. Determined to give birth anyplace but Libya, she boarded a rickety vessel despite the risks.

“I was ready to die with my unborn child or make it to Europe,” she said.

Only after giving birth aboard a German naval ship in the middle of the Mediterranean did she and her baby daughter, Sophia, begin making their way to a refugee center near Düsseldorf. She is awaiting a response to her application for asylum.

Interview with Somali migrant Rahma Abukar Ali, mother of Sofia, in Gelsenkirchen, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. (VOA/Abdulaziz Osman)

‘Libya may become the Somalia of … the Mediterranean. You will see the pirates in Sicily, in Crete, in Lampedusa. You will see millions of illegal immigrants. The terror will be next door.’

– Saif Gadhafi, one-time heir apparent to the late Col. Moammar Gadhafi, addressing media outlets, March 7, 2011.

Video Testimony: Sama Tounkara, 23, Mali: In a temporary camp run by the Italian Red Cross in Rome, Sama Tounkara tries to get some rest before continuing his northward trek.

Fleeing Mali’s chronic war and unemployment in the fall of 2014, the tall Bamako youth traveled to Gao before crossing the Algerian border into Tamanrasset. After six months of doing construction in Ghardaia, he moved on to Libya only to find things get worse.

“In Tripoli, every day people would come with guns to take our money,” he recalls. “Or they would ask us to come with them for a small job but, in fact, they would rob us.”

One night when uniformed men came and asked him to help clean up around the camp, he was again threatened at gunpoint. His offense? Simply asking to be paid for the work. That forced his decision to flee. Crossing the Mediterranean aboard a small vessel packed with 146 migrants, he thought he might die. But after seven long hours on the open sea, he was rescued by a European vessel.

Interview with Malian migrant Sama Tounkara. (VOA/Nicolas Pinault)

Video Testimony: Dalmar and Ahmed, both 16, Ethiopia: After nearly a month in Italy, these underage teens are still afraid to use real names.

Both former students, they were persuaded to leave home by friends who had already started new lives in Europe.

“There are many reasons why we left,” says Ahmed. “There is unemployment, and even those who [graduated] before us were idle and freeloading in the streets, so that we decided to leave.”

After Addis Ababa smugglers drove them within an eight-hour walk of the Sudanese border, they joined some migrants preparing to trek across the Sahara. After five days of walking and hitching aboard overcrowded pickups, they finally arrived at Ajdabiya, capital of the Al Wahat District in northeastern Libya, some 90 miles south of Benghazi.

“On the fifth day of traveling through the desert, we ran out of water,” Ahmed recalls. They were then handed to more ruthless smugglers, who routinely tortured migrants that refused to pressure family members for ransom by phone.

Dalmar’s scars are a testament to his six weeks in the Libyan smugglers’ den.

Sixteen-year-old migrant youths recount hellish journey from Ethiopia, in Milan, Italy. (VOA/Abdulaziz Osman)

Video Testimony: Morro Saneh, 16, Gambia: In a small migrant encampment in Rome, Morro Saneh recalls the night he slipped away from home. It was New Year’s Eve 2015 and, fearing fallout from an attempted coup against President Yahya Jammeh, the teenager absconded without telling family of his plans. After reaching Kaolack, Senegal, he paid $3,000 to get to Bamako, Mali, where he spent a month selling water in the streets. In Agadez, Niger, he became a bricklayer; in Tripoli, police took what little money he had and jailed him for 33 days.

Determined to reach Sweden, Saneh nonetheless warns young Africans who would seek out a life in Europe: “If I had to do it again, I wouldn’t do it. Too many risks.”

Interview with Gambian migrant Morro Saneh. (VOA/Nicolas Pinault)

Part IV: The Smugglers

Part IV: The Smugglers The Merciless 'Magafe'

Smugglers burned this migrant's hand during the dangerous journey from the Horn of Africa to Libya, leaving scabs and exacerbating blotches. (Obtained by VOA/Nicolas Pinault)

Each year, migrant and refugee traffic generates billions of dollars, and expansive international criminal syndicates are increasingly adept at reaping the profit. Capitalizing on migrants’ simple hopes for a better life, their guidance along irregular paths to Europe is as logistically vital as it is deeply exploitative.

Click or Tap Image to Open Gallery

From Khartoum to Calais, stories of abuse are tediously uniform: smugglers torturing migrants in the desert, extinguishing cigarettes on their hands, face or chest, tethering humans like animals to over-packed vehicles that ply Sahara sands, sometimes jailing them for ransom upon arrival in Libya.

Eritrean migrant discusses harrowing trip across Libya, in Milan, Italy. (VOA/Nicolas Pinault)

‘Sometimes magafe could not provide us wood or coal to cook the food … I saw our cooks using some of our boots and jackets to cook so that we would not die for hunger.’

– Hafsa, Somali female, in Rome using a common Somali term for smugglers

Interview with Sudanese Migrant Abdallah Arku. (VOA/Nicolas Pinault)

Even in Italy, smugglers operate in the open. One Eritrean told VOA he was warned against registering with officials, while others were held captive in a house in Catania for more than 10 days, released only after raising thousands in ransom.

Sixteen-year-old migrants from Ethiopia discuss being held captive by smugglers, interviewed in Milan, Italy. (VOA/Abdulaziz Osman)

Those who can afford to continue the trip find the network of illicit guides will change composition with the surrounding geography: from fellow nationals who guide them across the Mediterranean to Albanian Mafiosos who work the settlement camps in northern France. Even penniless migrants can continue their journey northward on assurances they can work to pay off their debts. According to Giovanni Abbate, a Sicily-based IOM official, for young women those assurances often translate into indentured prostitution.

Giovanni Abbate, official with IOM in Sicily, Italy. (VOA/Nicolas Pinault)

Part V: Conclusion

Part V: Conclusion The Road Ahead: Lives in Peril, Policy in Limbo

"The Jungle," a slum for migrants in northern France, is home to several thousand people hoping to cross the English Channel to start a new life in the United Kingdom. (VOA/Nicolas Pinault)

The perpetual dread of al-Shabab militancy drove Nimco Muse Ahmed, an impoverished Somali mother of two, to forge passage through the world’s largest subtropical desert, one war zone and an ocean crossing by flimsy rubber raft.

It was after arriving in Vienna, the proverbial “City of Dreams” that routinely tops UN prosperity indices, when she threw herself from the top floor of a former military barracks to the concrete below.

“I was in a chemically-induced coma for some time and broke both legs and the backbone,” says Ahmed, describing the convalescence that followed her first suicide attempt at Austria’s government-sanctioned refugee encampment at Traiskirchen, a former artillery cadet school located outside the capital.

Her dread had turned to despair on an unseasonably warm autumn night, shortly after learning her application for asylum had been rejected. Trying to muster the will to shrug it off as yet another stumbling block along the path to a better life, she says it was being awoken by a fistfight between neighboring Somali and Syrian refugees over a missing cellphone that pushed her to the brink.

“I was desperate because of difficulties and the fact that I still lacked reception as an asylee,” she says of the moment she decided to end her life. “People in Africa — especially Somalia — I would say, ‘There is nothing in Europe, so don’t dream about it.’”

“I see the reality now. The snow. I did not used to feel hunger in Africa which I feel now in here.”

– Nimco Muse Ahmed, Somali refugee in Austria

Interview with Somali migrant Nimco Muse Ahmed. (VOA/Abdulaziz Osman)

Hardly emblematic of what most sub-Saharan migrants endure after arriving in Europe, key facets of Ahmed’s story nonetheless mirror the common hardship of the uprooted masses.

Like the majority of an estimated 1 million other refugees who arrived in 2015 alone, her search for a better life meant leaving behind a family — whose savings she drained to gamble with death on the high seas — only to find herself homeless and, without a passport, stateless on a strange northern continent.

Unlike the Syrian, Afghan and Iraqi nationals who constitute Europe’s largest portion of irregular arrivals, however, Ahmed says sub-Saharans face a unique type of discrimination. Throughout immigration centers and encampments across the continent, she says, they’re treated as second-class citizens by their Arab and Afghan counterparts. The scuffle over a missing cellphone pushed her to the limit, she explains, because it was just the latest in a series of petty squabbles among desperate coteries of foreign nationals, and it was bound to end like the rest of them. Because the better-educated Syrian refugees could communicate their side of the story to camp officials, her African roommates, regardless of whether they actually stole the phone, would inevitably take the blame.

Main Sub-Saharan Migrant Destinations

Map based on European Commission sources indicates migrant destinations via Italy, through which the majority of sub-Saharan migrants arrive on European soil.

Policy in Limbo

For refugees such as Ahmed, there are no easy answers. With the 28-member EU still reeling from 2015′s unprecedented migrant influx, battles over Greek debt and multiple terrorist attacks, the political unity required to find a solution is in short supply. Indeed, the most recent European Economic Forecast predicts an additional 3 million migrants in the coming year, and Britain, one of Europe’s “Big Three” states, is poised to hold a referendum on whether to leave the bloc, a move that could precipitate a further continental unraveling.

The fence surrounding the port of Calais next to "The Jungle" in Calais, France. (VOA/Nicolas Pinault)

EU policymakers have no silver bullet to resolve the crisis; despite a pledge to relocate 160,000 eligible asylees across member states, as of Dec. 12 only 159 people had been settled. Canada welcomed a plane carrying the first of 25,000 Syrian refugees on December 11, while U.S. legislators are just gearing up for a second round of debates on President Barack Obama’s proposed plan to grant asylum to 10,000 Syrians. Immigration remains a polarizing issue on the American campaign trail, where leading Republican presidential hopeful Donald Trump has vowed to restrict entry to Muslims and deport any Syrians who might arrive under an Obama program. Despite substantial White House movement on immigration policy, even efforts to award visas to former Afghan and Iraqi battlefield interpreters have come up woefully short.

"The Jungle" migrant camp in Calais, France. (VOA/Nicolas Pinault)

As individual European nations work through asylum applications, management of refugee arrival hot spots in Italy and Greece has largely fallen to a hodgepodge of international aid organizations, volunteers and municipal authorities.

“Why is it that months into this crisis, it is still almost exclusively volunteers who are providing those arriving on Europe’s shores with … life-saving assistance?” Peter N. Bouckaert, Human Rights Watch emergencies director, wrote after a recent stint in Greece. “Why should volunteers still be providing life-saving medical care on the rocks of Lesbos, with not an ambulance provided by any government or inter-governmental organization in sight?”

Some news reports echoed the criticism, saying EU representatives are hard to find on the front lines of the crisis.

“Border management is primarily a responsibility of the national authorities,” a European Commission spokesperson said via email. “The European Commission and EU Agencies help and support member states and national authorities managing the situation on the ground — but they do not replace member states.”

Police patrols near the harbor beside "The Jungle," a massive migrant camp in Calais, France. (VOA/Nicolas Pinault)

Beyond domestic policy, the EU has sought to tackle root causes of flight from Africa. At a November summit on migration, EU and African Union leaders established a $1.9 billion emergency trust fund to help African countries repatriate displaced nationals. Malta, the island nation hosting the summit and once a top destination for migrants, pledged $270,000.

A month later, EU officials launched a $2 billion initiative to stem illegal migration from Africa by spurring jobs and development programs in the continent’s top migrant- and refugee-producing nations.

‘There are millions of blacks who could come to the Mediterranean to cross to France and Italy, and Libya plays a role in security in the Mediterranean.’

– Moammar Gadhafi addressing France 24 television in March, 2011.

Grand strategies to stabilize the Mediterranean basin pre-date Gadhafi’s fall. In 2011, Italy’s then-foreign minister, Franco Frattini, called for a new intercontinental order.

“The EU, other world powers and international institutions such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund should urgently develop an equivalent of the Marshall Plan for Mediterranean economic stability,” Frattini penned in a 2011 Financial Times op-ed, citing the U.S. initiative to rebuild Western Europe after World War II. “This plan must mobilize a critical mass of new European and international financial resources, in the order of billions of euros, to modernize the economies of the region and improve investment.”

Frattini urged EU officials to remove trade barriers between Mediterranean countries and to work on the strategy with the United States, “whose role remains crucial.” He encouraged more access to higher education — to strengthen the workforce and dissuade youths susceptible to terror organizations’ recruitment — and called cross-Mediterranean job-training programs “the best way to curb illegal immigration and trafficking.”

Conversely, one prominent migration analyst says the problem won’t be solved by addressing Africa’s push factors alone.

“The real problem is that individual states are not willing to take responsibility, because they behave very nationalistically and think they have to respond to xenophobic tendencies within their own countries,” Hein de Haas, a University of Amsterdam sociologist, told VOA, describing the crux of the crisis as the inability of member states to find a common response.

With refugees of conflict and political persecution protected by UN conventions, the EU’s increasing economic openness, he said, creates a demand for cheap migrant labor that’s incompatible with restrictive immigration measures.

“Whatever you think of the issue, you can’t deny that smugglers have a field day when you close borders,” he said. “So there’s no point in blaming the smugglers, when in fact the border restrictions have created this phenomenon in the first place.”

Migrant tents in "The Jungle," Calais, France. (VOA/Nicolas Pinault)

Because grand development strategies require generational timelines — and because there may be a fundamental disconnect between prevailing migration ambitions and EU trade and immigration policy — Elizabeth Collett, Brussels-based director of the Migration Policy Institute Europe, suggests looking to smaller-scale, regionally targeted economic planning.

“Large-scale development policy alone won’t limit migration,” she told VOA in a ranging interview on EU immigration policy. “But there are things that are much more specific in the short-term that aren’t necessarily about limiting mobility, but are about trying to create opportunities that don’t require people taking extremely dangerous journeys to what can often be a very disappointing end.”

Perhaps the question is whether the EU can refocus efforts on replicating what Gadhafi’s Libya once reliably provided: smaller industrial hubs of growth and job opportunities that offer people such as Nimco Muse Ahmed a third option that entails neither a return to the life she knew, nor the struggle to create a new one in Europe.

But even short-term stabilization initiatives may prove hopeless in the wake of a shaken post-Gadhafi Libya, whose porous borders only fuel anti-immigrant sentiment across various EU member states. While migration policymakers grapple with solutions, it may well be the answer lies not in the federal offices of Brussels, but where each story of displacement begins: in the careful — or too often incautious — weighing of risk and reward that guides so many along this perilous path.

Peter Cobus contributed reporting from Washington, DC.

Credits

Reported by Abdulaziz Osman and Nicolas Pinault.

Edited by Peter Cobus.

Web design and development by Stephen Mekosh and Dino Beslagic.

Project management by Steven Ferri.

Content production by Teffera G. Teffera and Ezra Fessahaye.

Comments